25 June 2023 marks the 48th anniversary of the declaration of the State of Emergency in India in 1975. That tyrannical period in the nation’s history ended on 21 March 1977.

In 2015, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary, we had carried the accounts of various NWMI members who had lived and worked through that period about their own experiences during that time. Their interesting reminiscences can be accessed here: Vignettes from the Emergency.

This time around, network members who have memories of that period – marked by press censorship, detention of political opponents, and so on –look back on the Emergency of the 1970s from the vantage point of the present time, especially in terms of media freedom and freedom to dissent.

* * *

My Emergency

Carol Andrade, Mumbai

Carol Andrade is a former journalist who is now a full-time media educator as Dean, St. Paul’s Institute of Communication Education, Bandra, Mumbai.

During classes on the History of Journalism, talking to a bunch of 21-year-olds, the subject comes up mandatorily. I face a bunch of eyes that are desperately trying to hide the fact that they are glazing over with boredom. You can just hear the rusty little wheels turning, as minds, unused to thinking for themselves, try to join the dots and underline that first principle in journalism – relevance. So, I tell it as a story, with plenty of drama, because teachers these days are also supposed to perform, like Elton John belting out Candle in the Wind for the late Princess Diana at her funeral.

Before I launch my tale, I show them slides of The Times of India’s front pages, a couple of days before June 26, 1975. What still jolts me is how bland the pages look on June 26, the day the Emergency was declared. The banner headline across the page came the NEXT day, on June 27, and it was matter-of-fact. ‘State of Emergency Declared’. As if the news was definitely important, but not earth-shaking, like a world war, and definitely not as blinding as Waking to Freedom.

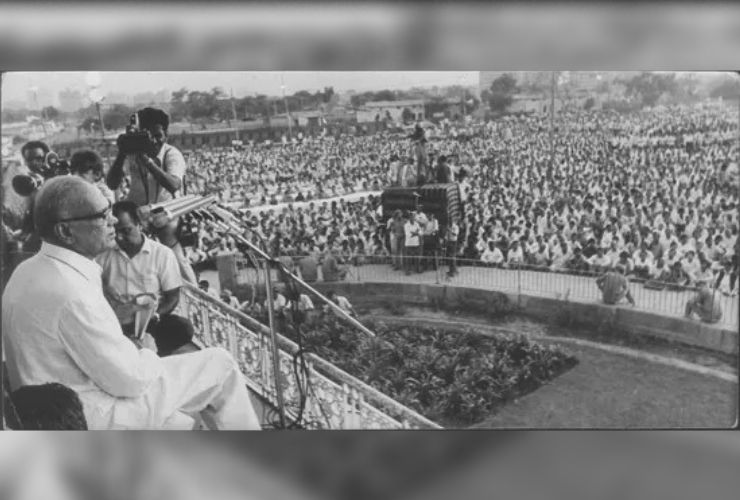

Look, I say, we did not even know that the decision had been taken, at midnight on June 25. Freedom fighter and activist JP Narayan, who had been advocating ‘Total Revolution’ at Ram Lila Maidan in Delhi, a couple of days ago, along with Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then of the erstwhile Bharatiya Jan Sangh, were already in jail and we did not know. Other activists and political leaders had been swooped up in the predawn raids, after most newspapers had been printed. In those days before the Internet or social media, it was possible for a would-be dictator to maintain complete secrecy, to present the nation with a fait accompli before addressing the nation on radio to announce that our liberties would be suspended for the present.

By 8 am, thanks to All India Radio, we knew what was happening, that the Cabinet meeting was over, that we were in a State of Emergency. As a trainee in the Times of India, attached to the Evening News of India for a month, I remember how aimless I felt, unsure of what the impact would be on us, but getting along with the usual gir gaya, mar gaya, jal gaya stories considered suitable for a tabloid. The newsroom that we all shared, was tense, with far less of the noise that was the norm. The Evening News of India was put to bed around noon and the sound of the press thundering away on the ground floor, was oddly comforting. And then they stopped.

I remember the low buzz in the newsroom congealing into silence as we absorbed the fact that the presses had actually stopped. It was like the absence of a heartbeat, unnoticed for a lifetime till it stops and you die.

Of one accord, and not a word said, the departments emptied as hundreds of us filled the stairs leading to the ground floor. By the time I reached, I could only join the silent crowd filling the long staircases leading to the floor. There were policemen present, constables and officers, looking awkward. The supervisor was showing the suited man seated in his chair, the dummies of the little tabloid. I don’t remember the stories on the front pages, but suffice it to say that there was no edition that day.

During the next 19 months, we did not cover ourselves with glory. I remember how disappointed I was that the legendary Khushwant Singh supported our Prime Minister. He had approved of her daughter-in-law Maneka Gandhi’s shenanigans in court during the Justice Shah Commission anyway, when she scattered the papers on his desk in protest against his decision regarding the validity of Indira Gandhi’s election. Durga riding a tiger, he had called her.

And there was not a word from arguably India’s most influential English newspaper when its senior assistant editor KR Sunder Rajan, was picked up from his flat in Cuffe Parade in the dead of night, sometime towards the end of 1976, for his writings in the foreign press against the Emergency.

The trains ran on time, nasbandi (forcible sterilization) was hailed as integral to population control, our gir gaya, mar gaya, jal gaya stories continued. Daringly, we experimented with headlines, felt so pleased when we came up with “Jhagda over Ragda”. Our finest hour, it was not. In the meantime, I had graduated from a trainee to the first woman reporter in the Bombay office. We lived our half-lives not knowing what it was we waited for. I covered the worst local train accident that Central Railway had seen up to then. It was much more interesting than trying to do political stories.

Then, inexplicably, Mrs Gandhi announced an election in 1977 along with the lifting of the Emergency. That same afternoon, the Brihanmumbai Union of Journalists and like-minded associations held the first morcha after the event. We walked down DN Road and veered off towards Azad Maidan, shouting slogans that seemed to impress no one and comforted ourselves by assuring each other that we had been brave all along.

Then the elections were held and Mrs. Gandhi lost her seat and we felt so terribly vindicated and discussed and debated and analysed the “why” of it threadbare.

In 1980, so sick was the country of the Janata Party, that she was back with a landslide victory. Today, I think that at least the powers-that-be have taken the lesson she left behind to heart. No need to declare an Emergency, just have a long, undeclared, soul-sapping one that defeats attempts to categorise it.

The Emergency and Me

Gita Aravamudan, Bengaluru

Gita Aravamudan started her professional writing career with Hindustan Times, Delhi in 1967. Currently an independent journalist, she has authored and published seven books.

In 1975, everyone lived in a state of suspended fear and this was truer of government employees who could lose their jobs or get punished for minor misdemeanours. I got my first taste of this when I visited my gynaecologist at the Trivandrum Medical College hospital to get an NOC for me to travel by air to Bangalore where I was planning to have my baby. She and I were on excellent terms and we often discussed whatever article I was writing at the moment. She knew I was an active journalist. On that particular day in November 1975, I happened to go for my appointment 15 minutes late. I was in for a shock.

Not only did my gynaecologist refuse to see me or give me that NOC, she also shamed me in front of all her staff and students. She said it was women like me who “have nothing else to do” who create problems for her during the Emergency. I was totally puzzled and taken aback by her words. But had no time to rue over them as I had to rush to another doctor and get that essential NOC as I was very, very pregnant!

* * *

I had taken a sabbatical from writing when the Emergency was declared in 1975. With an active two-year-old to care for and one more on the way, I was wrapped in my own bubble of domesticity and blissful motherhood. It took one year and the shocking murder of a student named Rajan to wake me up from my slumber and take cognisance of the real world around me once more.

I was 28 years old and had already worked for 7 years as a journalist. I had worked as a reporter with Indian Express in Bangalore and I was the only woman reporter in the city then. In 1970, I had moved to Trivandrum after marrying a rocket scientist who worked at Thumba. Those were the days when there were zero opportunities for a woman journalist in Trivandrum. Especially for one writing in English. And so, I had started freelancing. By 1975, over half a dozen years I had built up a good network of journalist friends as well as contacts in national publications and more importantly, picked up a working knowledge of Malayalam.

And now, I was on a break as my domestic commitments had increased. Trivandrum was far away from Delhi and in the beginning, we didn’t feel the turbulent impact of The Emergency. On the other hand, there was a sense of uneasy peace. The vociferous and omnipresent labour unions had quietened down. There were no placard holding protestors outside every business establishment. The road in front of the Secretariat in Trivandrum which was always blocked with jathas, was now surprisingly empty.

These were pre-TV days. The only news we got was from the highly censored newspapers. My un-doctored news sometimes came from my active journalist colleagues who were close enough to me to speak freely. Later, I heard about the atrocities of the forced family planning programme and the gagging of dissenters and many of the worst Emergency horror stories, after it was lifted.

When I came back from Bangalore three months later with two kids in tow, Achutha Menon, the popular CPI leader who was Chief Minister for the second term, was still in office. He continued to stay in this post till the Emergency ended in 1977. This proved to be beneficial as during his 7-year long stint he implemented important development projects, introduced laws which were beneficial to workers, enunciated a science policy and established several centres of excellence like The Chitra Thirunal Institute of Medical Sciences and Keltron.

I was by now getting lulled into thinking the Emergency was what we needed to get trains running on time and government offices functioning smoothly. Since I got only trickle-down news, I did not fully realise the horror of what was happening not just around the country, but right in the very state where I lived. Beneath that peaceful façade, hidden comfortably from public view, people were getting arrested after being falsely accused of being terrorists or Naxalites. They were subjected to inhuman torture to make them “confess” and sometimes they disappeared without trace.

It took the most sensational and infamous Rajan case to shake the whole of Kerala and wake us all up.

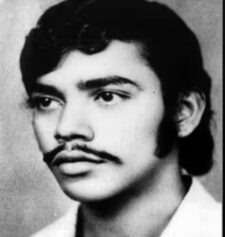

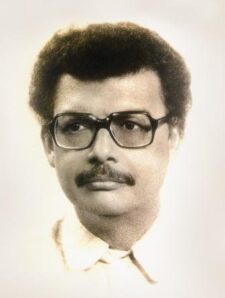

P Rajan was a brilliant student at the Regional Engineering College in Kozhikode. Though he lived in a politically volatile state like Kerala, he had no specific political affiliations. He was a good singer and an actor and a popular student. On March 1, 1976, when he had just returned to college after participating in an inter-collegiate Arts Festival, a group of policemen raided his hostel and took him away. That was the last time his friends saw Rajan.

Soon, the word went round that Rajan was arrested because he was a Naxalite and involved in a murder case. Those were the days when people were arbitrarily dubbed Naxalites and arrested. Especially if they were dissidents who opposed the Emergency.

Rajan’s father, Eachara Warrier, who was a Hindi teacher, tried desperately to locate his only son — but it was all in vain. He appealed to the Chief Minister Achutha Menon who referred him to the veteran Congress leader Karunakaran, who was then the Home Minister. Since Karunakaran represented Mala, which was Rajan’s family’s constituency, Warrier was hopeful that he would help him. But this was the Emergency when the police were arresting people secretly. So, they were tight lipped. No one could or would help the desperate father.

That was when my dear friend and veteran journalist the late Sam Rajappa got into the picture. He somehow managed to get himself lodged in the same jail where Rajan’s best friend was incarcerated. From him, he got the details of Rajan’s gruesome torture which resulted in his death. Sam’s article in the The Statesman was clinching evidence which Rajan’s father used subsequently in his quest for justice.

But the case was never resolved as Rajan’s body which was allegedly dumped in a reservoir was never found. The courts reopened after the emergency was lifted and Karunakaran who had become Chief Minster by then, was forced to resign after an adverse judgement. Jayaram Padikkal, who was the DIG Crime Branch then, was alleged to have ordered and supervised the inhuman torture of Rajan in a tourist bungalow at Kakkayam. Although Padikkal was convicted for this, not only was his conviction later overthrown, but he was also promoted over the years allegedly due to his closeness to Karunakaran.

We do not have an Emergency in our country right now. Neither do we have draconian press censorship. And we definitely don’t have a problem of paucity of information. On the other hand, we have a problem of over information. Myriad communication channels have opened up and information, both fake and real, leaks out of our very pores. There are no filters any more. Pictures can be morphed, information twisted and troll armies can be released to play havoc with our minds.

Dissidents continue to be arrested. Instead of being labelled Naxalites, they are now called terrorists or anti nationals. The underbelly of law enforcement has always depended on “encounter specialists” and they continue to act usually at the behest of the powers that be.

As in the past, false arrests are still being made and custodial torture continues, though perhaps not as blatantly as before. Forced sterilization is not an issue now as it was in the past. But new words like love jihad and land jihad have been coined to fan the flames of communal hatred. Today, like never before, secularism has also become a hate word. This generation has not even heard of democratic socialism which was a buzz word once upon a time nor do they know that the communist governments in our country were actually democratically elected.

So, everything has changed yet nothing has changed! But the good news is that despite everything that has happened, is happening and will happen, we survive as a democracy…and that I think is our biggest victory as a nation!

Go to Kashmir to understand what life is like under an Emergency

Kalpana Sharma, Mumbai

Kalpana Sharma is a journalist, editor, and writer. Currently an independent journalist and columnist with Newslaundry. In five decades as a journalist, she has worked with The Indian Express, The Times of India, and The Hindu, where she was a deputy editor and chief of the Mumbai bureau.

Forty-eight years after Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency on the night of June 25, 1975, people still ask: What was it like?

If today, in the year 2023, you want to get a sense of what life was like under the Emergency, go and spend some time in what was once the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Not as a tourist, or a pilgrim, but as a citizen who wants to understand what life is like for people in that region.

Since August 5, 2019, when the rights provided to the people of Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 were taken away overnight, and a full-fledged state was reduced to a union territory, there is a virtual state of emergency in the region, especially in Kashmir.

Think about it. Even as the central government led by Narendra Modi took this step, all political leaders who opposed the move were arrested.

The media, that has never had an easy run because of the presence of security forces, virtually fell silent. Internet was suspended making it impossible for journalists to file stories. They were questioned, intimidated, and detained.

Over time, what little remained of an independent media was snuffed out, while journalists who dared to question were charged under public safety and terror laws.

Four Kashmiri journalists are still in jail, and dozens more have had to either leave Kashmir or tread carefully as the sword of arrest or interrogation hangs over them all the time. Even leaving the country is not an option as several have found themselves on a no-fly list without prior intimation.

Many prominent Kashmiri journalists now write for international publications as their stories are rarely picked up by mainstream Indian media barring some independent digital news platforms.

Newspapers in Kashmir survive only if they toe the line as they are now entirely dependent on government advertising. Kashmir Times, the oldest English language paper founded by the veteran journalist Ved Bhasin and now run by his daughter Anuradha Bhasin, was forced to shut its Srinagar office when the lease was cancelled without explanation.

The Kashmir Press Club in Srinagar, an important meeting place for journalists, was also arbitrarily closed.

A media policy was put in place in 2020 that would penalise any publication or journalist who reported what the government considered “misleading” or “false”. In other words, nothing critical of government policies or programmes could be reported.

How is any of this different from what happened in the days following the declaration of emergency in June 1975?

Then too, opposition leaders were rounded up and put in jail. Most of them remained in jail for the entire period of the emergency.

The press soon fell silent as press censorship was imposed. Any publication violating censorship “guidelines”, which were frequently revised and updated, faced closure. No one could question the logic of these guidelines. You just had to follow them.

Even if journalists working for prominent newspapers wanted to report what they saw on the ground, they could not as their stories would not have been carried by their own publications. Their only option was to somehow sneak out the information they had collected so that it could be published in the international media.

A pall of fear that fell on the country after the first weeks of the declaration of emergency ensured that no dissent or political activity could take place. Such activity was compelled to go underground. Opponents of the Emergency, who had managed to evade arrest, had to devise ways to communicate without being detected.

For the 20 months that the Emergency lasted, people in one part of the country were unaware of what was happening in other parts. We only knew the full extent of the atrocities that were committed during the period when censorship was lifted, elections were held, and the Indira Gandhi-led Congress government was thrown out.

It will soon be four years since the abrogation of article 370. Have things changed in Kashmir?

Although some political leaders have been released, they have no role in the running of their former state because there is no legislative assembly. Normal political activity, such as public meetings and rallies are impossible to hold. Political parties are compelled to reach out to their constituents in ways that will not attract the attention of the authorities, people who take direct orders from New Delhi.

And what about the media? Before August 5, 2019, many highly regarded Kashmiri journalists reported for mainstream media houses. Their stories included reports on human rights violations and the views of ordinary people about the situation. They featured opposition politicians even if their views were unpalatable to those in power in New Delhi.

Today, there is a trickle of news from the region. What we read or watch are stories based on handouts by the security forces, and upbeat write-ups about tourism. It’s as if all the human rights abuses we read about in the past have disappeared.

So, even if a formal state of emergency has not been declared in Jammu and Kashmir, what people in the region have lived through in the last four years is not that different from the Emergency period of 1975-77.

What is more worrying is the absence of outrage in the rest of India about citizens in one part of this country being deprived of their basic democratic rights.

Authoritarianism finds fertile ground when the citizenry is immunised against violations of democratic rights, when people are willing to delude themselves that what happens in one region really cannot happen elsewhere, and when they swallow the propaganda that India remains the “mother of democracy”.

We need to recognise that what has happened in Kashmir is an experiment by this government to see how far they can go to deny citizens their basic rights. Why declare a formal emergency when you can manage without it?

A sense of déjà vu

Prema Viswanathan, Bengaluru

Prema Viswanathan reported for leading Indian newspapers from Mumbai, Delhi and Singapore in the 80s and 90s, later switching focus from mainstream journalism to market intelligence. Since her return to India in 2018, she has authored two books on art.

June 25, 1975, was, in a sense, a watershed in my political awakening. I was a naïve 22-year-old trainee journalist in the The Times of India, having arrived in Bombay just a few months earlier from Kerala, when Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency and imposed press censorship. I remember the excitement, trepidation and uncertainty that coursed through the second floor of the Times building on the morning of June 26. There was a protest meeting and a few senior journalists, including Khushwant Singh, editor of the Illustrated Weekly of India and KR Sundar Rajan, assistant editor of the Times, spoke out against censorship. But there was no plan of action as far as I can remember.

The days that followed saw several journalists doing an about turn even as others held on to their convictions. Khushwant Singh, sadly, became a supporter of the Emergency and the Gandhi family even though Mrs Gandhi turned down his plea to withdraw press censorship. Sundar Rajan heroically continued his tirade against the ruling regime and was soon arrested and put away in Arthur Road Jail in south Bombay. In Delhi, senior journalist Kuldip Nayar, who was then with Indian Express, was also put behind bars in Tihar Jail for voicing his opposition to the government’s actions. Veteran editor BG Verghese, a fearless votary of press freedom, was eased out of Hindustan Times. In Kolkata, NWMI member Rajashri Dasgupta was among those who were arrested, and kept in jail without trial, even before the Emergency was declared.

Most journalists who caved in, said they feared they would lose their jobs. Others felt any action would be ineffectual. The Bombay Union of Journalists was the site of a heated debate as its leader SB Kolpe refused to take a stand against censorship. None of them ever thought Mrs Gandhi and the Congress government would be dislodged after just 21 months. That the will of the people would prevail and that the dictator would lose the elections.

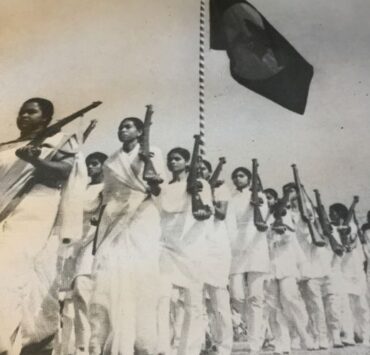

As a newbie journalist witnessing this real life drama, the Emergency helped me sharpen my political consciousness. As self-censorship became the norm in mainstream newspapers, several journalists with left and socialist leanings decided that the only way to combat the existing clampdown was to resort to underground publications. I was one of the many journalists who gravitated towards the underground leftist groups and began to participate in study circles led by Marxist ideologues. My spare time would be spent writing or typing up articles critiquing the goings on in the political and social arenas – whether it was the forced sterilisations, the Turkman Gate slum demolition or the clampdown on any form of dissent by the ruling dispensation. These loosely stapled cyclostyled bulletins would then be distributed among workers and the intelligentsia in a bid to keep the spirit of dissent alive. More than anything else, it made me feel that I was adhering to the principles of democracy and freedom of the press that I had imbibed while in college and which were now being tested.

In retrospect, my contribution was minuscule compared to the heroism exhibited by many of my compadres. According to a note put out by the Home ministry in May 1976, as many as 7,000 journalists had been arrested, several from smaller newspapers across the country. Some with radical leftist beliefs were even victims of police brutality.

What happened during the Emergency should have been a warning to those who believed in democracy and who thought that freedom of the press needs to be safeguarded. It is ironic that the very politicians who were victims of the Congress government’s ire and who are today part of the ruling BJP regime are unleashing attacks on any expression of dissent. India’s position has been steadily falling in the World Press Freedom Index since 2016, two years after the Modi government first came to power, when it was ranked 133.

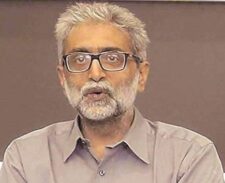

By 2023, the position has fallen to 161 out of 180. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, six Indian journalists are today behind bars, including human rights activist and journalist Gautam Navlakha and three Kashmiri journalists. Irfan Mehraj, a freelance journalist from Kashmir, had been arrested in March 2023 after being questioned by the National Investigation Agency, India’s premier counterterrorism body.

The same month, Bengaluru based Mohammad Zubair, editor of Alt News, an independent fact checking website, received threats on Twitter from Hindu fundamentalists, according to The Wire. Also in March 2023, Twitter withheld the handles of BBC Punjabi temporarily and suspended those of three journalists based in Punjab. Intimidation of women journalists, especially those from the minority communities, has also become alarmingly prevalent under the current regime. The spurious cases against Rana Ayyub and Saba Naqvi, to name just two, are prime examples.

For those of us who lived through the Emergency, the ongoing assault on press freedom brings on a sense of déjà vu. The only difference is that Mrs Gandhi made no bones about her intention to keep journalists on a leash. Today’s political dispensation is less forthright about its agenda. And therein lies the danger. Known threats are always easier to combat than unknown perils.

The Emergency and Today

Rajashri Dasgupta, Kolkata

Rajashri Dasgupta is an independent journalist with over 40 years of experience working in mainstream media. A peace activist, she is also actively involved in womens’ movements.

When the Emergency was declared, Bengal was already reeling under state terror; there were regular night raids in homes, and young people, activists and students were arrested without warrants, tortured, killed. In 1971, Cossipore-Baranagar was cordoned off by vigilante groups with the police as silent spectators. According to some estimates, 200 Naxalites were butchered in cold blood. Many of us were already in prison (I was arrested in October 1973) and we were bewildered by the word “Emergency”. What did it mean in real terms? What difference would it make to prisoners already living under brutal conditions? Jails were bursting with prisoners, imprisoned for years without trial. But we slowly understood how the State was hardening even more.

We found out that Siddhartha Shankar Ray, the infamous chief minister of West Bengal (1972-77), was the chief architect of the Emergency. Ray, a lawyer, was the crisis manager from Bengal. Having crushed the Naxalite movement, he was called upon by Mrs Gandhi to conduct “shock treatment” against the lawlessness and indiscipline in the country. It was he who proposed that an “internal emergency” be imposed, and he even drafted the letter for the President on how democratic freedom could be suspended while remaining within the ambit of the Constitution!

The impact of the Emergency hit our parents and families the hardest. We saw hope dying in the eyes of our parents, their smiles were forced when they met us during the permitted visits. Earlier they had some hope that justice and the courts would not fail us, that we would be released “soon”. And then the Emergency struck. It was our families who realised what this suspension of rights meant: that life in prison would get worse, that freedom would be elusive. Earlier they could bribe the guards for an extra five minutes during our meetings, or to allow us home-cooked food when we were taken to the court. This no longer worked, or the guards were asking for exorbitant amounts. Meetings with our families got shorter and fewer, reading material became erratic, and the meals in the prison were not even fit for rats, as we slowly understood what Indira Gandhi’s “shock treatment” meant.

Books, newspapers and magazines were always under scrutiny. The guards were paranoid about the colour ‘red’, whether the word was in the title of the book or on the cover. We were voracious readers hungering for every word, and we would lie to the bewildered guards when we argued that The Grapes of Wrath was about ‘angur’ or How the Steel was Tempered was to learn metallurgy… and the guards would usually let us have the books.

Those tricks no longer worked post June 1975. For months we were forced to flip only through glossy magazines. We would read to each other, about travels to exotic places, and we would “eat” even more exotic food as we relished each and every recipe in the magazines. Even the fine printer’s line in these glossies did not miss our attention. We were hungry. Starving.

The Emergency suppression led to a huge outpouring of underground literature in Bengal and elsewhere, alternatives to the mainstream media, and some were smuggled into the prisons. It was elating to read the literature of resistance to the sycophancy and fear imposed by Mrs G. Whether it was in poetry or political pamphlets, the writers wrote fearlessly and with passion. I remember Chandi’s cartoons, which captured the abysmal situation in Bengal during the Emergency, being clandestinely circulated among prisoners.

The well-known Calcutta journalist Gour Kishore Ghosh shaved his head in a symbolic gesture of bereavement at the death of democracy. He wrote a letter while in prison to his son about the agony of the “unjust encroachment on the writer’s freedom”.

A poet and writer who stands tall is Samar Sen who published Frontier with meagre funds throughout those tumultuous years. Frontier was perhaps the only journal to chronicle the agony of Bengal, from the brutal crushing of the Naxalite movement to the rights violations of the Emergency. A man of impeccable principle, Sen resigned his post of senior editor from Hindustan Standard on the grounds that the editorial policy was communal.

When we were released, we swore: Never Again. We realised how important it was to strengthen institutions like the judiciary and the media. We were also confident that we as a people had learnt our lesson to never allow our freedom ever to be curtailed.

Post 1977 were the heady days of the print media. There was a spurt of newspapers, columns, the best investigative journalism — it was like a dam let loose. It was in that scenario that many of us joined the media with idealism, with the belief that we could stand up to power. The 1960s and ‘70s were a period of hope, idealism, and protests, and not only in India; there was organised resistance worldwide.

Now, we are experiencing this hate-driven politics, a discourse that has taken over our daily life. Most frightening is how close friends and relatives mouth this narrative so casually. Yet we keep excusing them: “No, they are not like that, I have known them for years.” It is insidious and we are afraid to face the truth that, slowly, an incredible mass of people is toeing the line.

Some years ago, in Germany, people told us, “Hitler could not have emerged in one day. We were all part of it, complicit, we didn’t want to hear or read the signs. We were well-meaning academics, intellectuals, housewives, shopkeepers …” They asked themselves: “How did we allow this docile acceptance of unquestioned authority of the state that led to the destruction of our society?”

The BJP is not in power in Bengal but they have succeeded in changing the public discourse here as well, and that to me is frightening. Even in casual discussions, the comments are communal. People I have grown up with, friends, relatives, whip up fear about the Muslims. They talk about how they suffer the “Hindu hurt” and want to revive the “Hindu pride”. My maid tells me, “I couldn’t sleep last night, there was no electricity because the electricity is going to the Muslims.” Such comments weren’t made even a few years ago. Now I hear my otherwise lovely neighbour talking about the “Muslim” biryani.

Likewise, the government today does not have to change any law or switch off electricity as they did during the Emergency to pressurise the press; yet most media houses are willingly toeing the line of the government. As a senior editor commented, we are already crawling without being asked, while during the Emergency they had at least asked us to bend! The self-righteous and indignant journalism especially of the electronic media is being deployed to target minorities and political opponents. Student leader Umar Khalid’s speech for peaceful resistance has been craftily edited to show he was calling for violence! Many would argue that the composition of our newsrooms, of Hindu upper caste urban elites, is at the root of our faulty news making …it paves the way for capitulation, a “takeover.”

I live on hope, we can’t survive otherwise. We need deep, structural changes. Nobody will do it for us, we have to do it ourselves. I feel energised interacting with young people. I am a grandmother today and I want to be part of that exciting change.

Vidya Subrahmaniam, New Delhi

Vidya Subrahmaniam worked as Associate Editor, The Hindu, and subsequently as a Senior Fellow at The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy. She is currently a political commentator for Qatar-based Al Jazeera.

In the following article, Vidya recounts how the Emergency softened her anti-Congress stance, and made her more empathetic towards Dalit causes:

From Emergency to Now: The Wide Arc of a Hack’s Ideological Journey