By Editors

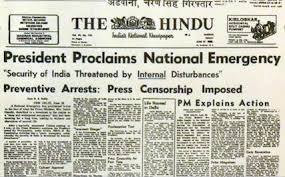

On June 25, 1975, a State of Emergency was declared in India. Though the official order was issued by President Fakhruddhin Ali Ahmed under Article 352(1) of the Constitution for “internal disturbance”, it was Prime Minister Indira Gandhi who de facto declared it. Until the withdrawal of the Emergency on March 21, 1977, fundamental rights were suspended, political activity suppressed, civil liberties curbed and the press censored. Thirty-nine years on, members of the NWMI recalled those turbulent times.

The discussion on the NWMI e-group was kick-started on June 26, 2014 by Bangalore-based Ammu Joseph, who wrote: “How about those of us who are old enough sharing our experiences with press censorship during the Emergency declared 39 years ago? I’ll go first, even though it’s a trivial experience considering the seriousness of the situation.”

Ammu Joseph, Bangalore

My encounter with the press censorship imposed during the Emergency was pretty unique. I’d just completed my communications course and had taken up my very first job (reporter and sub-editor at Eve’s Weekly and Star & Style – Managing Director JC Jain’s characteristic way of getting maximum work at minimum pay!) in Mumbai. Mr Binod Rao, my journalism teacher in the Social Communications Media course at the Sophia Polytechnic, had just taken over as chief censor in Maharashtra! Since I knew him, the management chose me to get Devyani Chaubal’s starry gossip columns passed by the censors.

I still remember my opening line: “Mr Rao, I never thought I’d face you across this table!” (or something to that effect). Put it down to youthful cheekiness, but I did feel better about the task assigned to me, having embarrassed him at least a bit.

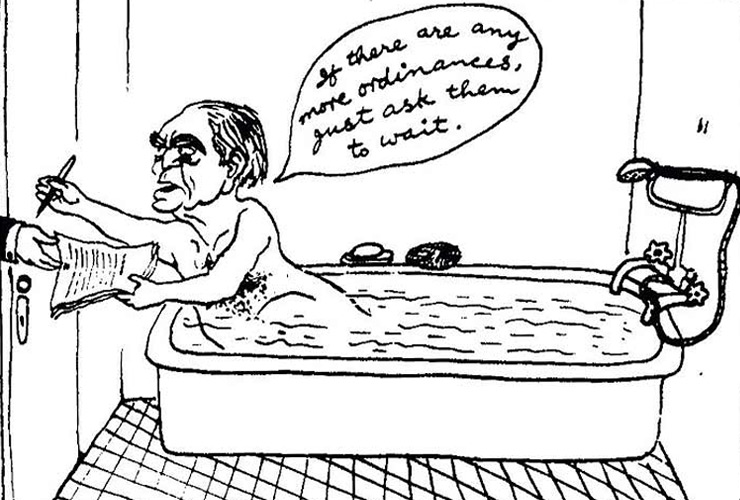

Ammu also reproduced veteran journalist BRP Bhaskar’s post on Facebook: “Lest we forget. This day/night 39 years ago, India came under Emergency rule. Reproduced here are Abu’s famous cartoon on President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed signing the ordinance in the bathroom and the front page of The Hindu which carried a report of the Emergency proclamation.”

Kalpana Sharma, Mumbai

On June 25, 1975, some of us who worked with a small weekly magazine called Himmat, edited by Rajmohan Gandhi, met at a friend’s house. That is where we first heard the news about the Emergency. At that point, none of us knew what this meant, particularly press censorship. Our editor, R M Lala, was out of the country and Rajmohan was not in Bombay.

The next day we began to piece things together. We were told that some “guidelines” had been issued for the press. Rajmohan and others consulted Soli Sorabjee and other lawyers and also spoke to AD Gorwala, who brought out Opinion, Minoo Masani who edited Freedom First, and several others. We were told that we should continue with business as usual because we were not writing anything that was against these guidelines.

Of course, that did not last for long. If I remember right, within a couple of weeks we got a notice from the censor’s office that we had to clear copy with them before printing. The censor in Bombay was Binod Rao, former resident editor of Indian Express. I knew him because when he was at Express, I used to constantly bug him to let us use, for free, photographs from IE. Himmat was run on a shoestring budget and had no money to buy photographs from agencies. And none of us had a camera! We also typed our copy, then sent it for typesetting (hot metal as it was called), then read the galley proofs (on damp newsprint) and then the page proofs before the issue was “locked” (literally!). And as we were a very small staff, everyone had to do everything.

That meant that I was given the job of taking copy to the censor’s office at Mantralaya. I had to wait outside for my turn, Rao would read the stuff and use a blue pencil – much like an editor – to cross out matter. I would argue furiously with him, but to no avail. A kind-hearted man outside Rao’s office (I think his name was Abhyankar) would always urge me not to be so argumentative: “These are bad times,” he would say.

So how to get around this? We discussed this threadbare each week in Himmat. We decided to take risks. First, we would not show our edits to the censor. Rajmohan’s column was also not shown. Nor were Letters to the Editor and also a humour page. The cartoon by Vins (who passed away just yesterday) was also never shown. And we had a column called This Was a Life where we wrote 300 words on a historical figure. That too was never shown. I took with me the sports copy, some current affairs and other random features.

We actually got away with this for several months. For instance, we carried a letter by Acharya Kripalani describing how his attempt to offer prayers at Raj Ghat was thwarted by the police who insisted it was an illegal assembly. Ultimately he, Sushila Nayar and his nephew, Girdhari, sat near the samadhi until closing time, daring the police to arrest them. No one else could report this news. We managed to sneak it in through the Letters column.

Inevitably, even these tricks did not work. Janmabhoomi press, that printed Himmat, received a notice that if it did not stop printing Himmat, its press would be seized. They asked us to leave even though they had been quite supportive.

At that stage, we had no option but to raise funds to buy our own press so that the responsibility for printing would be entirely ours. We put in an appeal for funds and amazingly, we got small amounts and larger ones and managed to raise around Rs 76,000. With those funds we bought two small machines, capable of printing only two A4 size pages at a time. But that allowed us to continue printing our edits and Rajmohan’s column without submitting these to the censor because the printline was ours. The rest of the paper was printed at a press in Worli where the owner insisted on the censor’s stamp on every page of copy given in for typesetting. The last forms that we printed at our own press were typeset in Fountain, the galleys (these were trays with metal type) carried by BEST bus to Prabhadevi. There the proofs would be read and corrections made by handset (that is one letter at a time!).

It was relentless work for a small team, but really exhilarating. In the middle of all this, the editor stepped down due to poor health and I was, at the age of 24, made the Editor! The fancy title did not change the nature of what I did – which was, along with my colleagues, everything from writing, subbing, marking photographs and proof reading. I couldn’t have asked for a better training in journalism.

When elections were declared in March 1977, we couldn’t believe it. During the Emergency, one just didn’t know if and when it would ever end. But because we were determined to keep the magazine going, and it was a weekly, there was really no time for navel-gazing or for feeling sorry for ourselves. We knew personally so many of the people who had been arrested. We expected that at anytime, Rajmohan would be picked up. And many of us also had close calls.

But we survived. Sadly, four years after the Emergency, Himmat died. It just did not have the capital to withstand the commercial pressures of running a weekly (later turned into a fortnightly) publication. Neerja Chowdhury, Rupa Chinai, Sanjoy Hazarika and Vins were part of the Himmat team during the Emergency.

You can read NWMI member Kalpana Sharma’s article on Himmat in the Emergency here .

Rajashri Dasgupta, Kolkata

The Telegraph, Kolkata in 2002 (to mark 25 Years of The Emergency) had brought out a special edition. I was asked to write a 500-word piece. Here it is:

We had shrugged off the news when we first heard the Emergency had been imposed. What difference did it make to prisoners like us the withdrawal of rights? Even prior to the Emergency, we were tortured brutally by the police for our political beliefs. For years, we had been imprisoned without trial. The conditions in the jail could not be more dismal, the food worse with the mish-mash of pumpkin, cockroaches and lizards for flesh.

We were soon to realise the difference. The raids by the jail warders increased. Books were confiscated, even Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath was perceived to be subversive. Anything the colour red (colour of revolution), from book jacket, to saree to a picture we had painted that had red was seized. Letters from home were even more heavily censored, paragraphs blacked out. Warders kept a stricter vigil on us during the fortnightly meeting with our family or when we were taken to court in the police van. Bribes to the jail staff had to be almost doubled whether it was to smuggle in food or to post a letter.

Worse, we saw the hope die in the eyes of our parents. Their voices no longer carried the assurance of our release, their smiles barely veiled the panic in their heart. Letters from home read of inane things like the weather unlike earlier exhortations of courage and faith. Our parents realised long before us that efforts to expedite our release was useless as long as the Emergency lasted. If the courts earlier were indifferent to the plight of prisoners, it was definitely not going to stick out its neck now.

But there were prisoners who lived like kings and made their bonanza during this period. They strutted around the jail premises in freshly starched kurtas with their lackeys running after them with huge tiffin carriers of food from home. They were known popularly as the COFEPOSA prisoners for violating the foreign exchange laws. Despite their imprisonment, their business thrived as deals were made from the offices of the jailor. Strong rumours were that they were “imprisoned” to provide them protection from the taxman’s noose.

Life in prison took a dramatic turn in 1977 when Indira Gandhi declared elections. Mrs G was the most hated and despised person, to us she epitomised autocracy and death of democracy. There was laughter once again in my father’s eyes when he whispered to me in court that the movement for the release of political prisoners was gathering momentum. “Believe me, it won’t be long.”

The excitement was palpable. One of us managed to smuggle a pocket transistor into our prison cell. As we took turns to stand guard, others listened to the news under cover of blankets to hush the sound. But on the night of the election results, we threw caution to the wind as we sat crowded around the radio. With every defeat of Mrs G’s men, we could hear shouting and screaming in the neighbourhood. Past midnight, when the news of her defeat and that of Sanjay poured in, the thick walls of Presidency Jail trembled with the roar of approval. We danced and sang and were intoxicated with the dream of victory over cups of diluted tea. After a few months, we were released under general amnesty. But that fateful night in Presidency Jail what mattered most was the defeat of Mrs G. It signalled the hope for democracy.

Sumi Krishna, Bangalore

The Emergency was declared overnight but the run-up perhaps began in 1973-74. I joined the Hindustan Times (HT), Delhi in late 1972 after working for a couple of years as a lecturer at Indraprastha College in Delhi University. I was 26, one of six or seven women on the HT staff including Prabha Dutt, Shyamala Shiveshwarkar, Rashmi Saxena and myself (then Sumi Sridharan); a year or two later more women were recruited (including Smita Gupta and Sevanti Ninan). BG Verghese who had earlier been Indira Gandhi’s Press Advisor (and speech writer) was then the HT Editor. I was involved in BG’s pet project, the ‘Village Chhatera’ column, and therefore had more interaction with the editor than most other junior reporters. BG was open to ideas from the junior-most staffer and it was an exciting and educative experience to be a journalist at that time.

In August 1973 came BG’s now famous editorial on the action in Sikkim (till then a ‘protectorate’): “Kanchenjunga, here we come” and the next year another editorial that said plainly: “A merger is arranged”. Soon after, in May 1974, there was India’s first “peaceful” nuclear blast in Pokhran – the HT cautioned against “false notions of power” but I don’t think it was overly critical. In the same month, despite being sympathetic to the Indian railway worker’s demands for higher wages and better working conditions, HT did not support their massive three-week-long strike (following the failure of negotiations and the arrest of union head and MP, George Fernandes). I was among those who covered the strike, but field reporters were not constrained by the newspaper’s editorial opinions. In early 1974, HT had also begun raising the issue of corruption in politics. Cases involving LN Mishra (who was Minister for Foreign Trade – now called Commerce – and later Railways), the Modi flour mills, and Maruti motors (with which Sanjay Gandhi was involved) were being relentlessly covered. The proprietor KK Birla’s difficulties with BG’s independent stance and the attempt to ease him out because of ministerial pressure soon became common knowledge. In 1975, the HT staff led by Assistant Editor CP Ramachandran (a leftist) filed a complaint with the Press Council (which was then located at 10 Janpath) and thereafter the matter also went to court. The HT management argued that freedom of the press applied to the proprietor and not the editor. But in September 1975, the Delhi High Court rejected KK Birla’s petition. The Emergency was declared in June 1975. Despite the High Court verdict, within hours, BG was dismissed. There was an immediate (illegal) pen-down strike by the journalists and some 75 of us signed a scroll that was presented to BG. Later five or six of us (including Upendra Vajpayee, who covered Parliament, and CP Ramachandran) went to meet the Information Minister VC Shukla to protest the dismissal. I was the only young person and the only woman in the group and some cautious colleagues told me that I should leave these things to the senior men and not “take such risks”. In the event, the only thing that happened to me was that I was ticked off by VC Shukla who said curtly: “Madam, what do you want me to do? Put Mr Birla in jail?”

The atmosphere in HT was tense after that but the two News Editors were also upright men, supportive of democratic freedoms. One had to find themes and ways to write which would not draw the attention of the censor; so non-news features flourished. We also tried to be present at happenings even if we could not report freely about these.I remember the Turkman Gate slum demolition in April 1976, ordered by Sanjay Gandhi purportedly to “beautify” Delhi. Over 700 houses and old havelis were razed and police fired to disperse protestors. This was one of the most notorious incidents of police excess during the Emergency. Later, when the Janata government came to power an official enquiry was conducted.The burnt-out scene at Turkman Gate, on the morning after, was for me personally the most painful. The incident was caught up with the residents’ protest against Sanjay Gandhi’s population control programme and forcible abortions. I was pregnant at that time and had recently been to the women’s hospital, Lady Hardinge (now called Sucheta Kripalani Hospital) to consult with the gynaecologist and try to register. The head of the department said, as I was not in government service, they could not guarantee that I would get a hospital bed for the birth but it should be alright. I was then sent to a junior doctor to be examined. The first thing she said was: “You are an educated person. What are you doing? Why have you become pregnant so soon after marriage? You should terminate this pregnancy. Here is the form.” I said I was 27, going on 28, not too young surely, and I was not going to terminate. The young doctor, obviously, had a quota of “voluntary” pregnancy terminations to complete and she was persistent. We had an argument; I refused to be examined and did not go back there.For a long time after the Turkman Gate firing, I carried a dull sense of guilt: Just a couple of months earlier, I had been able to walk out of Lady Hardinge; the women in Turkman Gate had no options.

Jyoti Punwani, Mumbai

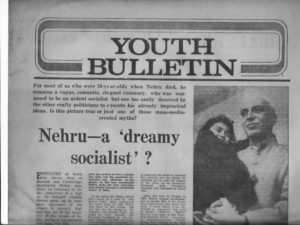

I was working for MJ Akbar at the Free Press Journal (FPJ) in Bombay during the Emergency, my second year in journalism, bringing out a weekly ‘Youth Bulletin’ as part of their daily afternoon tabloid,The Free Press Bulletin.I didn’t interact with Akbar much, I was too junior – he just hired me after a meeting that lasted 10 minutes. In fact, he hardly asked any questions – obviously a three-page bulletin once a week didn’t count for much! FPJ was then a training ground for journalists. You had to work there when you started off, no one else would take you – not the Times of India (TOI) with its “trainee programme”(which I flunked), not The Indian Express (IE) where you went to intern as part of your journalism course. FPJ still owes me and many like me payment – it was notorious for delayed payments.But you got your byline and learnt the ropes, and entered the glamorous world of journalism.

I spent close to two years there, working under Rauf Ahmed, Neera Sen,S Venkataraman (he taught me to do away with full-stops after initials), and having just come back from the US, called me “baby” and made me bristle. He succeeded Akbar who left everyone in peace, while Venkataraman was all over the place, supervising everything. JS Rao, Hebbar – they were also part of FPJ. It was the real world of journalism – cigarettes, informality, laughter.

During the Emergency, I did a story on the demolition of a large slum called Janata colony in Trombay, to make way for a BARC colony extension. It was a full-page Sunday story, cleared I think, by Neera Sen. On Monday morning, Akbar told me that the censors had hauled him over the coals for publishing it. To date, I have no idea how it went past.

A lot of stuff was written by radical left activist Anuradha Ghandy and others like her – all my friends – in the ‘Youth Bulletin’. Rauf Ahmed, who later became a leading film journalist, was in charge, but he never interfered, except to design the pages.Brought out every Monday,‘Youth Bulletin’ was pretty radical, but everything went through, including articles on fee hikes and student strikes.’

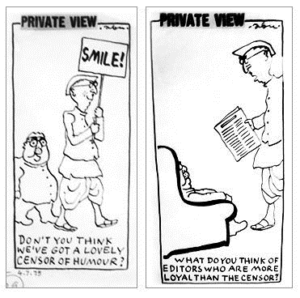

I was there when the Bombay Union of Journalists (BUJ) discussed the imposition of press censorship just after the declaration of the Emergency. It was stormy, and shameful. SB Kolpe, who many think was a progressive doyen, spoke in favour of self-censorship. Dinkar Sakrikar, a Socialist, opposed it and resigned as editor of Clarity, in protest.Clarity was the first weekly to be brought out by a journalists’ cooperative. Kolpe headed the co-operative, and I had worked there as a trainee.

Sakrikar went on to give a fiery speech in Elphinstone College, during the Emergency. I remember the packed hall, with students spilling out, and the deafening applause that greeted him at the end. This was a government college! Having grown very friendly with him after working under him, I used to often accompany Sakrikar when he went to meet the Socialist scholar and writer Durgabai Bhagwat at the Asiatic Library. They would have meetings on how to oppose the Emergency. I remained on the periphery of those meetings. I also remember the radical group to which I belonged, Proyom (Progressive Youth Movement) led by Kobad Ghandy, having cloak-and-dagger meetings as if the police were following us, in my uncle’s house – all of us landing there separately – my uncle had no idea what we were discussing. He was kind enough to leave the house when we were there. Ironically, that building is now owned by Maharashtra Samajwadi Party chief Abu Asim Azmi, who runs his party like a dictator.I was so radicalised by Kobad and Anuradha that I refused to vote in the historic and crucial post-Emergency election, believing (as I still do), that elections in India mean only a change of exploitative rulers. (I must clarify that I have opted to vote for candidates I liked twice/thrice since.) Not all the urging of my colleagues in Eve’s Weekly where I then worked, made me change my mind. It’s ok, even without my vote, the dictator was ousted.

Anjali Mathur, Mumbai

I was in the thick of the resistance movement during the Emergency and thought I’d share one experience from that period, even though I was not a journalist then. I was doing my PhD at the university and headed a student’s organisation called Proyom (a wing of the CPI-ML). We decided to have a meeting of students to build up the anti-Emergency movement. Some Shiv Sainiks came to know about it and informed the police. We didn’t want the students to be taken into custody so I gave myself up as the organiser of the meeting and persuaded them to let the others go. Incidentally, such arrests and disruption of peaceful meetings were the norm and there was an atmosphere of fear everywhere that is difficult to imagine now. I was convinced I was going to be in jail for a long time, as had happened to so many friends and fellow activists in that period. But, somehow I was lucky, and the police let me go after some questioning. My husband and I had to go underground soon after this, because the police raided our house and there were warrants for our arrest. We shifted to Pune and worked among the workers and Dalit women till the emergency was lifted.

May it never happen again. Many NWMI members were too young to have been working during the Emergency; yet memories are sharp.

Ranjita Biswas, Kolkata

I was new to Calcutta during the horror of the Emergency, looking after home and baby, and could get the drift of what was happening only through the newspapers, which would have been heavily censored ; we didn’t even have a TV set and today’s 24×7 news coverage was not even dreamed of.

Manjira Sarkar, Kolkata

These anecdotes bring alive a crucial period in our history. I remember living next door to the Anand Bazar Patrika (ABP) and my father being a writer himself, we had several journalists dropping in. I was still in school and heard him say that Gour Kishore Ghosh (he later received the Magsaysay award for journalism) who had opposed the Emergency had shaved off his hair in protest and wanted to grow it back only when the Emergency was lifted.

To end, Ammu reminds us that it’s even more sobering to remember that the dark times persist for many people — many of us only hear of a few cases (Binayak Sen, Soni Sori, etc.), but so many others are still routinely imprisoned, tortured, etc., without even the fig leaf of the Emergency.

C Vanaja, Hyderabad

I first heard about the Emergency when I came to the university in the 1990s and started working with a civil liberties group. I heard many stories of not only being jailed but tortures and killings. My longest engagement with Emergency stories was when I translated Memories of a Father by Eachara Varier whose son Rajan was picked up and killed in Kerala during the Emergency. Incidentally I did that Telugu translation immediately after my companion Venu’s arrest and it was a very intense emotional experience even to translate it.

We also need to remember that jails have not changed much since 1975. For the past six months I have been engaged with a friend who spent four years in a small Jharkhand jail. We are putting together her experiences of being incarcerated in an overcrowded women’s jail. It is the story of the same rotten food, the same bribes and the same old stories as Rajashri mentions from thirty years ago.

Jency Samuel, Chennai

What I remember about the Emergency is Rajan’s case. I think I was nine. I remember reading in Tamil about Rajan being tortured with a granite post and telling my classmates about it. For many days I was haunted by the thought of him being tortured. I couldn’t understand how a human being could do that to another. MISA was also being talked about then.

Geeta Seshu, Mumbai

Does my recollection count? I wasn’t a journalist – I was barely 11 years old. But I do distinctly remember discussing it with my father. I used to read the newspaper avidly even at that age and he explained it to me. I remember saying that I thought the Emergency was wrong and a “bad” thing. I also have a hazy remembrance of delivering some papers to the lawyer KG Kannabiran’s house – he lived near our home in Secunderabad and my father sent me off to give him some papers. No idea what they were and why I was sent to do this and (delicious thought) whether there was some cloak-and-dagger operation I was part of. Alas, both Kannabiran and my father have passed and I’ll never know.

Rina Mukherji, Kolkata

I was only a precocious schoolgirl , and this was when I learnt about what an internal Emergency was supposed to be. Until then, I had only known that an Emergency accompanied a declaration of war. My father was with the Reserve Bank of India, and it was around this time that the Jimmy Nagarwala case (of bank fraud perpetrated in the name of Indira Gandhi) had come up, in the aftermath of the 1971 war. I remember him talking about how bankers were extremely unhappy with Mrs G, and the disturbing fact that Nagarwala had always been known as an honest man. Her mode of operation, and dishonesty, was the subject of criticism. The Emergency, when it came, was perceived to drown all this.

Editor’s Note: This article was updated in June 2023 with the addition of more photographs. The order of the write-ups has been rearranged as well.

To share more stories of the Emergency, especially related to the media, please write to editors@nwmindia.org