By Swarna Rajagopalan (guest post)

Over the years, I have come to bristle and splutter when asked to justify the importance of including more and more women — an equal number, even — in electoral nominations and political appointments. It’s 2021, I want to snap, and you are still asking me this. But late last week, the two major parties in a state whose rationalist and progressive politics denizens preen about, between them nominated 27 women for a total of 350 seats contested. Under 8% is pathetic by any standards.

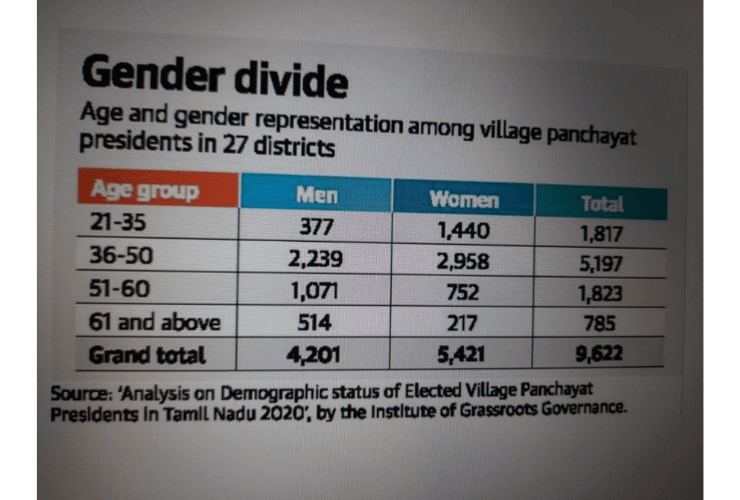

Tamil Nadu is not a state in which women are invisible. Traveling through the state you can see women in public spaces, working, moving around, going about their business. The Panchayat reservations have given the state some outstanding leaders under 50 and these women are vocal and well-known. Women are also entrepreneurs — owning small businesses, running significant corporate ventures or working in the social change sector. SDG gender equality indicators are generally better for Tamil Nadu than for most other states. If, despite this, the two major parties in the state, with their large grassroots networks, could not find more women to nominate, it’s time to swallow the splutter, take a deep breath and lay out at least six reasons why women’s representation — indeed, gender diversity in political representation — is important.

1. Democracy is about representation

The underlying premise of democracy is that those whose interests are affected by government should have a say in its decisions. “No taxation without representation” was an important slogan in the American Revolution. If a government speaks or acts in my name, or its actions affect my survival or interests, I should have a say in selecting or electing it, I should have a right to participate in that decision-making, I should have my representative in that process and I should be able to inform, question or challenge that decision. This is what democracy means, not just the now-annual election tamasha that we witness.

According to this understanding of democracy, it stands to reason that every gender, every community, every section of society, every possible identification or location, should be represented in government. Perfect representation and perfect parity may be impossible but the closest approximation thereof should be our ideal.

Would men tolerate the exclusion to which they subject everyone else? Never. Look at the discussion in every training session on violence against women: “With all these laws (that protect women from the violence of patriarchy), who will protect men from their misuse?” Patriarchal entitlement makes male political hegemony look like the natural order of things. Therefore, although clearly, without equal and fair representation, you cannot have democracy, we harbour the delusion that you can.

In short, if you want to boast about democracy, you must make sure everyone is fairly represented — in voting, in contesting, in cabinet appointments, and thereafter. Democracy is equal access and equal voice.

2. A question of justice

This time, the press and social media carried photographs of aspiring candidates being interviewed by the DMK leadership. The leadership sat around a table while at least some of the candidates stood. With female candidates, that visual was particularly offensive — female supplicants being assessed by male overlords. But even setting that aside, one of the key questions in the interview seemed to be about resources: how much could the aspirant spend on the campaign?

Across the board, women own less property, access less credit and earn less for the same work as men, even if and when they can go out to do it. This is even more true of other marginalised genders and groups. To make resources a decisive factor in candidate selection is to institutionalise exclusion. Around the world, political scientists have documented reasons why women are less likely to opt for political careers to start with. Politics is structured around a male monopoly, where men in politics typically handle very little care work. So, hours are long and uncertain, and while travel during elections may be part of the work, there is no reason why evening and night meetings cannot be rescheduled, for instance. Furthermore, not only do women need to arrange and pay for help with their care work, they also commute or travel in contexts where the infrastructure is not reliable or safe.

Also, women usually relocate upon marriage and that means they are not in a position to bring to politics the network of kin and school and college friends that men can count on. Add to this the ever-present threat of violence against outspoken women or anyone from a marginalised group that dares to challenge the status quo, and the cards are stacked heavily against women finding politics an attractive option.

If, when they do, they are also required to produce adequate capital to finance their own campaigns, this is the political equivalent of locking the door and pushing all your furniture against it to guard against a break-in. It is not democratic. It is not fair.

3. Under-utilisation of the available talent pool

Choosing your candidates or your ministers from a small subset of less than half the population means that you are choosing to ignore a great deal of talent. There are women and gender minorities who possess skills, knowledge and experience that you are choosing to overlook in your selection process.

“We would love to choose women but WHERE do we find them?” is a standard excuse. You open your eyes and there they are: in your party, in the Panchayats, in Self-Help Groups, in Residents’ Associations, in social welfare activities, in professional work, in NGOs and, most important, in people’s movements. These are also the places you often find your male candidates. These are people with experience in identifying problems, articulating needs, finding and negotiating solutions, mobilising people and support, and rallying resources. With male dominated politics and policy-making, we are using only a tiny fraction of this experience for the greater good.

The large number of women who have leadership and administrative experience at the grassroots level would also bring a deep understanding of context as well as the community networks to facilitate consultation before decision-making and, also, implementation.

4. Perspectives

Policy-making that is based on one view of the world — more or less that of men, privileged across the board or within their communities — is flawed and apt to fail. Better, fuller representation across the board — from grassroots consultations to the very apex of executive power — will bring more experiences and points of view to inform our understanding of problems, needs and solutions.

The most obvious example is that of housing with toilets placed at a distance, past unsafe stretches for women. Similarly, government distress shelters whose phones are only answered during the work week do not take into account that need knows no schedule. Not accommodating undocumented residents in informal housing when you distribute emergency supplies is another example.

Including women, and members of marginalized gender, caste and class groups, offers a corrective to this poorly informed policy making. Members of these groups, internally diverse, bring completely different experiences to the discussion of any problem. The best way to access these perspectives is to make sure that they get to be a part of the decision-making process.

5. Essentialist arguments

There are arguments for women’s inclusion that are based on stereotyped views of the nature of all women. Women are equated with motherhood and therefore assumed to be more nurturing, more concerned about families and less inclined to seek power for its own sake. By extension, it is assumed that women will seek peaceful resolution of conflict, resist the temptation to enter into wars and reduce spending on arms. Rather, they are likely to prioritise health, nutrition and education — children’s needs, for instance. Similarly, women are considered by some to be more honest and less likely to play diabolical games for influence.

While essentialist arguments like these are easy to challenge empirically, when you increase the number of women in government, you increase the probability that some of those women are going to reflect some of these characteristics and, therefore, shift internal conversations a little.

This is also true for the argument against quotas: that what we want are feminists or gender-sensitised individuals – and not necessarily women – in positions of power. The more women, the more gender and sexual minorities, the more people from marginalised castes and communities, the more likely that feminist and gender concerns will be raised.

6. Optics are good!

Finally, in an era when all arguments are decided by market concerns and brand equity, here is what should be a clincher — the optics of including women and other minorities. All-male panels, committees and cabinets look wrong in 2021 and it is no longer just feminists who notice them. Meetings with a substantial number of female participants make a good impression on voters although they might not, unfortunately, care enough to mandate them.

A party or government that wants to look like it cares about democracy and people must be and be seen to be inclusive. To speak of gender equality, as Tamil Nadu’s parties and, indeed, all Indian parties do, while doing nothing to augment the numbers of women you nominate and treating women in your manifesto rhetoric as if they are mindless sop-recipients, is to get the optics of contemporary democratic performance quite wrong.

What is to be done?

In 2016, before the last Assembly election, Prajnya came up with a Gender Equality Election Checklist which lists simple measures for political parties to start with as well as criteria voters might use to indicate how important gender equality is to them. We also used this in our sporadic efforts to monitor election seasons that followed. Our hope has been that mediapersons would adopt the Checklist in their own features and interviews.

Unfortunately, a quick search for news reports reveals that, except The News Minute, no one has made the miniscule proportion of women candidates headline news. This is still, apparently, a non-issue. Paternalistic sops are reported without question — just as they are proffered without much thought. Interview questions and discussion panels are much more focused on back-channel manoeuvres than the elephant in the room – democratic politics, which in fact stands only on one kind-of-sort-of-leg: privileged men.

It is going to take relentless gender-sensitive reporting, continuously holding people accountable and challenging the ‘women-and-children’ paternalism of manifestos and speeches, if we are going to see any improvement at all in the track record for inclusion. Small organisations like Prajnya and academics like me can persist, but we cannot make a dent in the patriarchal thinking that makes single-gender government acceptable without the power of the media to amplify the same questions and concerns. This NWMI blog, which monitors election reporting, is an important step, but it is only the first of many that are essential and have been urgent for a very long time.

Swarna Rajagopalan is a political scientist with an interest in gender issues. She is also the founder of Prajnya, a nonprofit that works towards gender equality.