By Editors

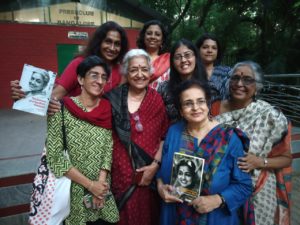

Pioneering feminist economist Devaki Jain joins members of the NWMB for an informal chat at the Press Club of Bangalore.

It’s the 1950s. A young, sari-clad woman and her white, male companion are trying to thumb a passing ride. She’d be striking anywhere in the world but in the Europe of seven decades ago, she is particularly so. The bindi. The pleated pallu. The sparkly nose stud. The two of them are hitchhiking their way from England to Sweden and back. In your head, it’s an utterly incongruous image, like a bad photoshop job. But as you sit there taking in Padma Bhushan awardee Devaki Jain, you can see in full technicolour the exotic and vivacious 20-something “freak”, the daughter of a Dewan (premier) in the princely state of Gwalior, studying at a trade school in Oxford because that’s the only place that would give her a full scholarship.

Devaki is one of those giants that you stumble upon while meandering along being a journalist. A Fulbright scholar, she was one of the first developmental economists to start a conversation on women’s hidden contributions to the economy. As an expert consultant, she has been working extensively with the United Nations, and has authored a book on how the women in the organisation shaped its programmes for women, particularly in the Global South, and its impact on the UN’s elemental goals of justice and equality. Back in Karnataka, she is part of several policy task forces and has had an active role in framing credit schemes for rural women.

A celebrated feminist economist, yes. But Devaki is also in the midst of a brewing political storm. So, it would have been crazy to pass up an opportunity to meet her. She is fresh from the event to relaunch slain journalist Gauri Lankesh’s tabloid, one year after her assassination on September 5, 2017. Devaki is rankling from the complaint filed against Girish Karnad who attended the event wearing the sign, #MeTooUrbanNaxal. She wonders if there is a symbolic way we could support him during the protests planned in Delhi on September 15 against the Bhima Koregaon arrests. In fact, she is one of the five petitioners who moved to the Supreme Court against the arrests of prominent social activists on August 28.

The four other petitioners, including close friend Romila Thapar, are staunch Marxists, according to Devaki, who is the sole Gandhian in their group. And she wishes this was emphasised more. Because it’s not just the Left that is disturbed by these arrests, and the insidious chain of events that preceded it. “The BJP mustn’t be allowed to come to power in 2019,” she says while wondering if women are more active in their support for BJP, considering they are supposedly more religious than men. But that shouldn’t stand in the way of a feminist-led anti-far right mobilisation, according to her. Devaki has written extensively about the effectiveness of women’s unions and groups as a socioeconomic force. And right now, she wishes they were a political one too.

Because unlike some other anti-BJP movements that are still trying to find their feet, the political mobilisation of women can change the equations quickly, if there is enough momentum to unite the diverse women’s groups, Dalit organisations, and women-led unions of garment workers, service sector workers, government factory workers and more. “A month ago, several domestic workers’ unions marched in Delhi and met with the likes of Rahul Gandhi, demanding comprehensive regulations that would grant them rights and protection under the ILO. This is a big win for domestic workers,” she says. And there is no question of tarring feminism with a political brush because feminism IS politics, says Devaki. “It had always been a political fight. You can’t call yourself a feminist if you aren’t an activist as well.”

Heavy stuff aside, the fun part of the evening is Devaki’s charming and personal anecdotes about her feminist awakening and the years around it. She confesses that she has always been thankful for the two-year sabbatical she was forced to take after graduation because during this time she was able to learn her ‘podis’ and her pickles. She reminisces about an awkward bride viewing, where she was literally asked to sing. “I didn’t,” she clarifies while acknowledging that, in the marriage market, her fair skin allowed her past the gate without having to provide credentials of her singing and cooking. In fact, this still bothers her, the unfair advantage her complexion gave her over her own dark-skinned sisters.

An advantage that she unabashedly seized to create a new fork on the road for herself. One that’d take her to such far-flung places and so often that her frenemies and professional rivals would accuse her of “always having her bags packed”. She’d rub shoulders with presidents and dictators. She’d lie on a beach in Greece while road tripping from Oxford to Delhi, through roads and borders that no longer exist. To the awed audience in front of her, she says there is no great secret sauce really. Just a simple, almost naïve, lack of fear – whether she was a driving through Afghanistan on her way home or flying away from home towards her contentious choices.

September 8, 2018