This article by network member Urmi Rahman is based on the paper she presented at the International Conference on Bangladesh: Revisiting Freedom and Independence organised by the Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, on 30 and 31 March, 2023. More than 100 people attended Urmi Rahman’s session, including former Member of Parliament Professor Malini Bhattacharya, and members of the Bengal chapter of the Network of Women in Media, India.

By Urmi Rahman

I am very proud and fortunate to have been a witness to the war for freedom for Bangladesh. I am one of the millions of people who have their personal stories about the war. This is my story.

We were then living in the coastal town of Khulna. My father was the Forest Manager of Khulna Newsprint Mill. I was doing my BA Honours in Bengali Literature. My sister, Tandra (Tonu), was just in kindergarten school. My youngest sister, Shoma, was born later. Khulna is a pleasant, peaceful town, culturally very rich. The Mill colony was located at the junction of two rivers – Bhairab and Rupsa. It was a nice colony with a park, swimmimg pool, club house, etc. A high wall separated the residential bungalows from the rivers. Behind that wall was the Naval Base.

In those days not every household used to have television sets; radio was more popular. Our club house had a TV and we used to go there to watch the news. The Awami League, a mainly East Pakistan based political party, had won the last election with a decisive majority, but the administration was not prepared to hand over rule to them. In protest against this, on 7 March 1971, the leader of the Awami League, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, launched a non-cooperation movement. The whole of what was then East Pakistan joined in that movement. Some paramilitary forces, known as the East Pakistan Rifles, also took part in the non-cooperation movement. However, soon they had to go into hiding at a secret camp in order to take shelter against the Pakistani Army.

Some of the ladies from our colony, including my mother, started sending cooked food to the camp. They had to do it secretly, hiding their activities from the West Pakistani officers who were posted in the Mill and lived in the colony. These officers were supportive of the Martial Law Regime imposed by General Yahiya Khan. We were very disappointed by the stand taken by these officers.

Dhaka TV was telecasting patriotic songs and news during the non-cooperation movement. Suddenly one day the telecast was off the air. Later we came to know about the terrible genocide that had taken place in Dhaka on 25 March 1971. Later, on 27 March, the Pakistani Army reached other towns and areas in the country, including Khulna.

They tried to attack the Khulna Newsprint Mill Colony. When they reached the Junior Colony they faced some resistance from the officers and staff. These people tried to resist that attack with whatever they had with them, and some of them were killed. An officer we used to call Alam Chacha was stabbed to death with a bayonet.

That day the Army left without doing much more harm, but the Newsprint Mill Colony was later attacked again by a group of miscreants. The group consisted of Biharis who had a big settlement outside the gate of the mill. They obviously supported the government of Pakistan. I am not saying that all the people in that settlement were hooligans, but some of them were and they raided and attacked our colony. Most of us had gathered at the General Manager’s Bungalow, which was on the bank of the river Bhairab. The group killed a number of people in the colony. Someone later told us that when he ventured to visit the scene where the killings had taken place after the hooligans had left, he saw a one-year-old baby lying on its mother’s blood-soaked, dead body and crying. It made us very sad.

For many days after this the officers and the rest of us did not dare to stay in the Newsprint Mills Colony. We left the mill and took shelter at the home of my father’s friend, whom we used to call Putul Mama. He lived in Khulna city and was the General Manager of the Pakistan Match Factory. Many of the other mill officers also left the colony and took shelter in the houses of friends or relatives. But such respite was short-lived.

The Khulna Newsprint Mill was Pakistan’s only newsprint factory – so the authorities were keen to keep it open. They went to Khulna city in search of all the officers and brought them back to the Mill along with their families. We all came back to our colony. After a few days, my father told us that, if the situation became worse, he might have to run away and hide somewhere. That would be easier for him to do if he was alone, without the rest of us to think about. So he decided to leave us with his elder brother.

We were to travel by river on a steamer service called `Rocket’. There was another reason for doing that. One of my classmates, Manju, was with us. After doing her Higher Secondary she had joined the famous Brojolal College to study towards an Honours in Chemistry. Her father had been transferred to Barisal and my parents had invited her to stay with us. During that crisis period my mother was more worried about her safety than about ourselves. Since Barisal was on the route of our steamer, we could drop her off there. So we took the steamer and dropped Manju at her father’s place in Barisal; she left us in tears. We carried on with our journey and finally reached Dhaka, the capital city of East Pakistan.

My Chacha-Chachi and cousins were very happy and relieved to see us. When we reached Chacha’s house, we came to know that the youngest two among Chacha-Chachi’s seven children (they were twin boys) had left home, leaving behind a small note saying that they were going to join the Liberation Army as freedom fighters. We were naturally very worried for them; at the same time we also felt very proud.

Chacha’s eldest daughter, Nina, and her husband, Mahmud, were both doctors; so was another daughter, Rini. They spent most of their time at the Dhaka Medical College Hospital, where they worked with the other doctors looking after many wounded victims of the Pakistan Army. At home, Chacha’s youngest daughter, Piu, six months older than me, and I were very depressed that we were not doing anything to be helpful.

One of my school friends, Miru, who was also a distant relative, lived nearby. We were allowed to visit their house. She was also depressed like us. Then, one day, she told us that if we were interested we could translate some leaflets from English into Bengali and her brother, Shaukat, could secretly send them across the border from inside East Pakistan. We were quite happy to do something.

At that time we were doing some embroidery to kill time. We used to go to Miru’s house taking a file full of designs for embroidery, hiding the leaflets among the designs. But one day I was almost caught. I was alone, returning from Miru’s house in a rickshaw, hiding a leaflet among my designs for embroidery. To return from their house, we had to pass Peel Khana. That day, I saw that para-military forces were checking all the vehicles – cars and rickshaws. I panicked; all my blood seemed to turn into water. I could not think of any way out. But when my turn came, the para-military soldier took one look at me and, for some reason, asked the rickshawala to carry on, showing no interest in me. I don’t know why he let me go. Maybe he had a sister of my age, or maybe he was a Bengali and forced against his will to work with the Pakistani military regime. But I thanked my luck and that unknown soldier.

However, that work was not enough for us and we were still depressed. Then came a family friend and my Chachi’s colleague, Dr Shafiullah – Shafi Mama to us – along with an intellectual and writer, Dr Borhanuddin Khan Jahangir. They asked us if we wanted to do some work for the Muktijuddha – Liberation War. We were very happy to say yes.

They asked us to do several things. First, we collected money and clothes for the freedom fighters, whom we called Muktijoddha. We only went to the houses of people we knew were supporters of the Muktijuddha. Then, one day, Shafi Mama and Dr Jahangir asked us to drop off a letter to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). When the India-Pakistan war broke out in December, they asked us to go to Sadar Ghat, on the banks of the river Buri Ganga, to check how many bunkers and trenches had been dug there. It was quite risky work. We were fairly young and Sadar Ghat was quite far from our home. We told our parents that we were going to Miru’s house and took a rickshaw to go to Sadar Ghat. Luckily we were able to finish counting the bunkers and trenches without raising anyone’s suspicions and returned home safely.

My Chacha’s second son was an exceptional person: kind-hearted and popular with friends. His name was Tubul; we called him Tubby. He had some contact with the guerilla freedom fighters. They occasionally came to the city to carry out some operation or other and had to stay somewhere. They could not stay with their families as there was constant surveillance on them. So they stayed whereever they could – like the house of a friend with whom they could not be readily connected. My Chacha’s house was one such shelter for them.

This particular group was named Crack Platoon. Some of their operations involved discouraging students who were still attending schools and colleges. They blasted bombs in educational institutions and in the vicinity of high-end hotels and guest houses, like the Hotel Intercontinental where foreign journalists usually stayed. We were very happy to do something for them, although we knew that it was risky business. We frequently cooked for them. One day one of them had tears in his eyes. He told us that they had forgotten that the colour of rice was white. The rice in their camp was mixed with soil and grit – so its colour was like dirt. Hearing that made us very sad; it also made us think that our twin brothers who were engaged in fighting for our country must be filling their bellies with dirty food.

Our eldest sister, Nina, and her husband, Mahmud, decided to cross the border. Some of Mahmud Dulabhali’s (brother-in-law’s) friends had started field hospitals on the other side of the border, and they wanted to join those serving there. Our parents decided that Piu and I should also go with them because it would be much safer than staying in the besieged city. We were ready to go with Nina and Dulabhai. Arrangements were made.

In the meantime, some guerilla fighters were captured by the Pakistan Army. And one among them must have given the army the address of our house while undergoing torture. One day before our departure, the Pakistan Army turned up at our house and searched the whole place. My Chachi’s father, Tamijuddin Khan, used to be the Speaker of the Pakistan Assembly at one point. There was a photo of him with US president John F. Kennedy in our drawing room. One of the Pakistani soldiers asked how that photo came to be there. Our brother, Tubby, told them that he was their Nana (maternal grandfather). The soldier commented that he could not understand how a relative of such a ‘Shariff’ (noble) person could be a ‘Gaddar’ (traitor) like this. They could not find anything incriminating in our house – yet they took Tubby away with them.

We had to give up the plan to leave the country. We were very upset. One day later, around dawn – 5am or so, the phone rang. It was the Officer in Charge of the Ramna Police Station. He told Chachi, “If you want to see your son, then come now, but you will have to leave before 7am, when they will be taken to MP Hostel.’ Later we came to know that those taken into custody were subjected to interrogation and torture. My mother and Chachi hurriedly took whatever cooked food there was in the house and went to see Tubby. Ma and Chachi went to meet him with some food every day, over several days.

Finally, Tubby was released. Our elder brother and sisters had tried in various ways to persuade influential people that Tubby was innocent. Maybe he was released because he happened to be Tamijuddin Khan’s grandson. When he returned home, he never took off his shirt in front of us. But one day, when he was about to go for a shower and took off his shirt unconsciously, we saw signs of torture all over his back. “I never changed my statement,” he told us with a half-smile. “I knew that if I did they would think I know more.”

Then, in December, war broke out between India and Pakistan. Before and during that time the Pakistani Army indiscriminately dropped bombs on people’s houses. Some of our relatives came to Chacha’s house for shelter. During the war there were frequent cockfights in the sky between Indian and Pakistani aircraft. We used to run up to the rooftop at all hours to watch the manoeuvres. The elders used to get very angry and always ordered us to come down. Of course, they were actually scared that we could be hit by stray bullets.

When the Indian Army finally called upon the Pakistani Army to lay down arms, the order was announced from the sky, from helicopters. Ultimately Pakistan had no choice but to surrender. It was on 16 December 1971 that Dhaka and the rest of East Pakistan became independent. The Pakistani Army was asked to surrender their weapons to the Indian and Bangladeshi Armies. The event was organised on the Race Course Ground.

Even on that occasion the Pakistani Army threatened to fire at the crowds, mostly Bengalis, standing on the sides of the streets and cheering. So while our elder brothers and male members of our immediate and extended families went to witness the surrender, we girls were not allowed to go out. We decided to use our time to prepare some posters to hang in different places in Dhaka the next day. But we did not have any paper or colours. Finally we used old newspapers and ‘Alta’ (lac-dye, which Bengali women use to anoint the soles of their feet).

That night we were too excited to go to bed. Quite late at night, we heard the sound of a jeep at the gate, followed by banging sounds. At first we were a little scared because, over the past nine months, we had become habituated to being badly startled by such sounds coming without warning. On 16 December we heard a similar sound again. At first we tried to ignore it but, since it was persistent, we had to open the gate.

To our delight, we found the Guerilla Muktijoddhas who had taken shelter in our house during operations in Dhaka city outside the compound. They were dressed in lungis, jubilantly waving firearms. Their faces split into broad smiles as they told us that they were just outside the city when the surrender was announced. They decided to come to our house to pay their respects to our family and thank Chachi for taking motherly care of them. All of them were animated and kept on talking. They asked Chachi for food, saying they were hungry. We did not have anything at home. So we decided to wake up our local shop keeper. He could only provide some biscuits and fluffed rice (‘murree’). The freedom fighters were happy with that.

The next day we told the elders that we were going out to join the Victory Day celebrations. Miru also came and joined us. First we went to the Language Martyrs Memorial or Shaheed Minar to put up posters. While we were doing that, two or three persons approached us and asked if they could interview us. We asked for their identity, and a very handsome person told us they were from All India Radio (AIR). I politely asked for his name because, during the previous nine months, we had become fans of some of the AIR broadcasters. He told us he was a journalist and his name was Chanchal Sircar. I felt very excited as I used to listen to his radio talk, called ‘Amar Mote’(In my opinion), with my father. Chanchalda interviewed us and, from that moment onwards, as long as he was alive, I enjoyed his affection.

After that we went to a few other places. Everywhere people had gathered to celebrate the victory. The crowds were full of joyous excitement but also very disciplined. They moved out of our way and made room for us to proceed. They kept telling each other, ‘Move away, our sisters have come.’ Some more freedom fighters entered the city and joined these gatherings. We greeted each other, spoke to them. Everyone was jubilant, happy and excited.

This is my personal account. What I was able to do during the freedom struggle was a drop in the ocean. But, overall, the women of Bangladesh made a huge and remarkable contribution to the war of independence. Some worked as guerilla fighters, some nursed the wounded or sick people, including the Muktijodhhas (freedom fighters). Some carried messages from one place to another. They hid weapons, they gave shelter to the guerilla workers. Groups of men and women went to different camps and refugee shelters to entertain people there by singing patriotic songs. Women were very active in every aspect of the struggle for independence. Many became Shaheed (martyrs), many others lost their near and dear ones.

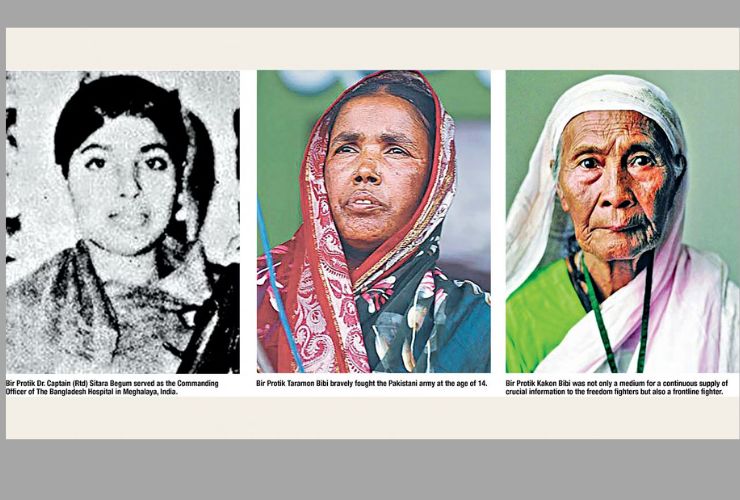

Women political leaders went to different refugee camps and recruited female volunteers. One of these women freedom fighters was Shirin Banu Mitil, who joined the war face to face disguised as a man. Kakon Bibi was a freedom fighter who also worked as a secret agent during the liberation war. Apart from them, Ira Kar, Gita Kar, Laila Parveen Banu and 36 others also joined the liberation movement. Since there was a shortage of weapons, some of them worked in field hospitals and others joined the forces in different capacities.

Sufia Kamal was a writer, feminist leader and political activist who took part in Bengali nationalist movements even in 1950s. At one point she was the president of the biggest women’s group in the country, Bangladesh Mohila Parishad. Her two daughters, Sultana Kamal and Saeeda Kamal, left the country during the liberation struggle and joined the Mukti Bahini (guerilla resistance force). They worked in a field hospital set up by Bangladeshi doctors on the other side of the border. Dr Sitara Begum, Taramon Bibi, Rounak Mohal Dilruba Begum, Ferdousi Priyabhashini and Rokeya Begum also participated in the liberation movement.

Three of these women – Sitara Begum, Taramon Bibi and Kakon Bibi – received one of the highest national awards, Bir Protik, for their contributions to the war for freedom. However, all of them remain immortal in the annals of the glorious liberation war that led to the birth of Bangladesh as a nation.

Urmi Rahman is a journalist and author now based in Kolkata. After working for 12 years with a number of Bangladeshi newspapers/journals and the Bangladesh Press Institute, she joined the BBC World Service in London in 1985 as a producer-broadcaster. Urmi has a number of publications to her credit, both fiction and non-fiction. She is a member of the Bengal Chapter of the NWMI.

Read: NWMI Bengal meet with Bangladeshi journalist Urmi Rahman – NWM India