By Rajashri Dasgupta

Nandigram is no ordinary village in West Bengal. Located about 150 kms from Kolkata, it was the epicentre of the agitation by farmers against land acquisition in 2007. Today it is once again in the eye of the storm: the state’s Chief Minister, Mamata Banerjee, has decided to fight for her Assembly seat from the constituency on April 1, during the forthcoming, eight-phase state elections.

Nandigram, located in Purba Medinipur district, is where Banerjee first tasted major political success. As an opposition leader during the 34 years of Left Front rule (1977-2011), she had supported and led angry protests in Nandigram and elsewhere against the controversial acquisition of agricultural land for a chemical hub and special economic zone. Women were in the forefront of the resistance, taking on the forces of the state as well as party cadre. In the brutal crackdown that followed, 14 people were killed and several women were raped (the exact number is not known and estimates vary, as the two reports linked here demonstrate).

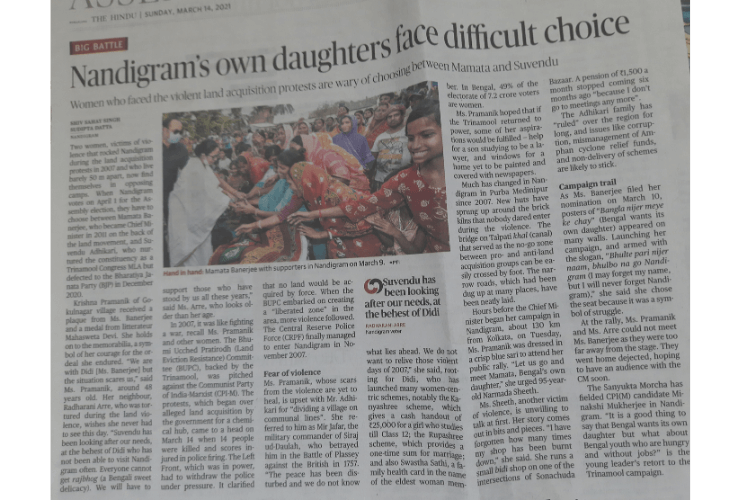

However, as The Hindu recently reported, Nandigram’s own daughters are divided ahead of the upcoming polls. During the agitation her supporters included women like Radharani Arre – interviewed for the March 14 report in The Hindu – who were in the forefront of the movement. In 2021, the bitter challenge for power is not between the All India Trinamool Congress (aka TMC) and the Left Front, but between Didi and her former protegee, Suvendu Adhikari, who recently joined the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Left parties, including the Communist Party of India (Marxist), from whom Banerjee wrested power to become CM in 2011, trails behind along with its ally, the Congress party.

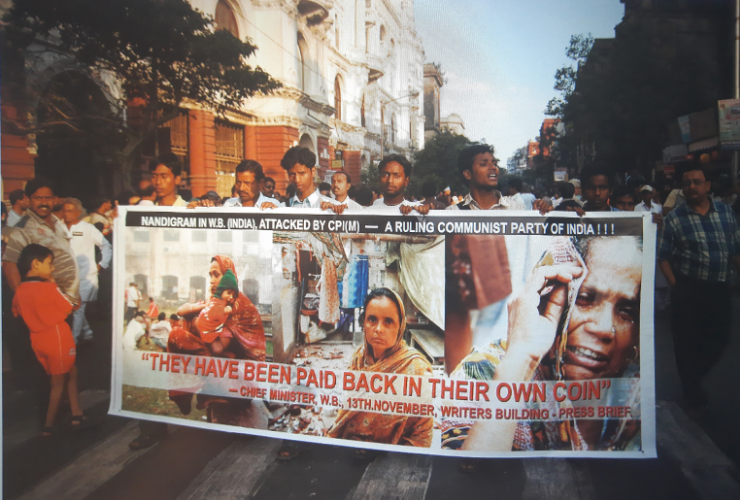

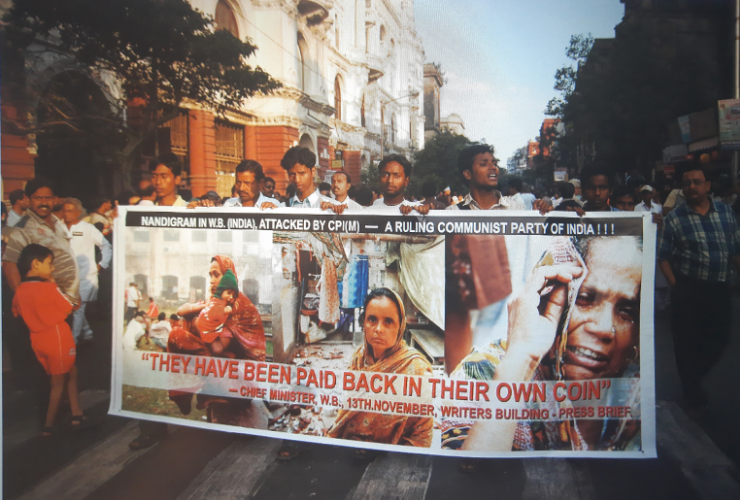

March 14, 2007 will remain a blot on the landscape of progressive politics and one of the darkest days in West Bengal’s history. The police fired indiscriminately on a peaceful gathering of villagers protesting the acquisition of agricultural land, killing 14 people and injuring several others. Among those killed were two women and, in the ensuing mayhem, many women were raped and several others, like Radharani Arre, were sexually assaulted. There was widespread shock and disbelief at the unprovoked firing, all more so since it was unexpected of a Left Front voted into power in 1977 by a huge majority, promising progressive land reforms among other programmes. In fact, Nandigram was then a known Left base, as peasants had benefitted from the reforms initiated by the Left Front.

From 2006 onwards the state began to witness a series of angry protests by farmers under the banner, “Save Farmlands,” against the acquisition of agricultural land for industrial purposes. The ruling Left Front government was enmeshed in controversial land takeovers in its bid to quickly industrialise the state and provide much needed employment.

In Singur, located in Hoogly district, it had taken over almost 100 acres of multi crop land in 2006 for a car factory to be set up by the Tata group. Following fierce resistance by the local people, the factory project was abandoned in 2008; it was ultimately shifted to Gujarat with subsidies provided by the state government then headed by Narendra Modi.

In Nandigram, the state government had proposed to set up a Special Economic Zone with a chemical industrial complex on 10,000 acres of agricultural land, with investment from the Indonesian Salim Group. The memory and experience of the Singur land takeover added to the local people’s anxiety. From January 2007 the agitation, led by the Bhoomi Ucched Pratirodh Committee (BUPC, Committee to Resist Land Eviction) in the Nandigram region, took a swift turn. Protesters dug up roads to prevent police from entering villages, Left Front cadres were attacked and driven away from their homes; several homes were burnt down.

To break the BUPC hold in the region, the administration sent 3000 policemen to enter the villages on March 14 morning. Protesters quickly gathered to block police entry. A large number of women left their household chores to squat in dharna, some singing hymns. “We never ever dreamt the police would fire on us. We were sitting peacefully, singing and chatting with each other,” women protesters told the all-women fact-finding team who visited Nandigram after the shooting. By the end of the day bodies lay strewn around and several people who were injured hid with neighbours, afraid to seek medical help, while those in critical condition were rushed to the hospital.

It is said that if the Singur agitation triggered the downslide of the Left Front state government, Nandigram brought it to its knees. There was widespread disgust and disbelief even among Left supporters, students and intellectuals against the police firing. Seizing the opportunity, Mamata Banerjee rode the wave to electoral victory in 2011 to become the new CM, taking advantage of the sentiments of the rural population as well as Left supporters who were tired of the arrogance of the ruling party.

The lotus flag was then conspicuous by its absence; the turf war was between the ruling Left Front and Mamata Banerjee. Ironically, today, her once right-hand man, Suvendu Adhikari, who galvanised the protests against land acquisition and nurtured Nandigram, is the CM’s challenger as the BJP candidate.

If Nandigram stirs images of the controversial land grab and violence, it will be also remembered for the exceptional role of the women who were in the forefront of the protest movement. They had participated in every demonstration and protest in large numbers, voicing their concerns. Even on March 14 fourteen years ago, women with their children had formed a human shield, peacefully squatting in front of the armed police, little suspecting what was to follow.

Months after the police firing, with peace yet to return to the troubled region and men unable to return home and cultivate their land for fear of retaliation, it was the women who strove to bring about a semblance of normalcy in their lives. We once lived as a community, rued several women. Look at us now, we are so suspicious of each other, we don’t even talk to each other, they told the fact-finding team in 2007. They were afraid of possible attacks from goons who heckled them saying, “Leave your lamps burning and the door of your home open. We are coming for you.” Despite their fears, they continued to fend for their families and homes, feeding the children and caring for the elderly.

However, when it came to the peace process in conflict-ridden Nandigram, both the Left Front that espouses gender equality and Mamata Banerjee, who never missed an opportunity to drag women like Radharani Arre to the stage as victims of Left violence, forgot the women of Nandigram. Women were absent in the negotiations and, of course, among the leadership conducting the talks. Their views on issues of land, displacement and compensation, or even on jobs and employment, were never taken into consideration.

Ten years later the region is again in the eye of the electoral storm. In a masterstroke of political strategy, Mamata Banerjee abandoned her traditional city constituency, Bhawanipur, where she is from, to challenge the BJP on the very turf that catapulted her into political success. Again, Mamata Banerjee has shrewdly cultivated the slogan, “Insider(Banerjee) vsOutsider (BJP of North India), for her campaign. She has also remoulded her image from that of the elder sister, Didi, as she is popularly known (some even think it is her real name!), to being the meye – or daughter of the soil – urgently requiring people’s support (read votes) against the BJP outsiders! This tactic may pay off if voters feel compelled to protect and help their own meye to vanquish the outsiders.

Be that as it may, The Hindu’s Shiv Sahay Singh and Sudipta Datta deserve to be commended for their special story on Nandigram Diwas, focusing attention on women who faced violence during the 2007 protests and who now, as voters, are faced with a choice between Mamata Banerjee, who politically supported the land movement, and Suvendu Adhikari, who was the TMC MLA from the area for years but has now joined the BJP. It is good to see that a subsequent Press Trust of India (PTI) story on how justice still eludes rape survivors in Nandigram 14 years later has been carried by several news outlets across the country, including Deccan Herald, The Week, Outlook and East Mojo.

Editor’s Note: Rajashri Dasgupta was part of the all-women fact-finding team that visited Nandigram in 2007.