By Revathi Siva Kumar

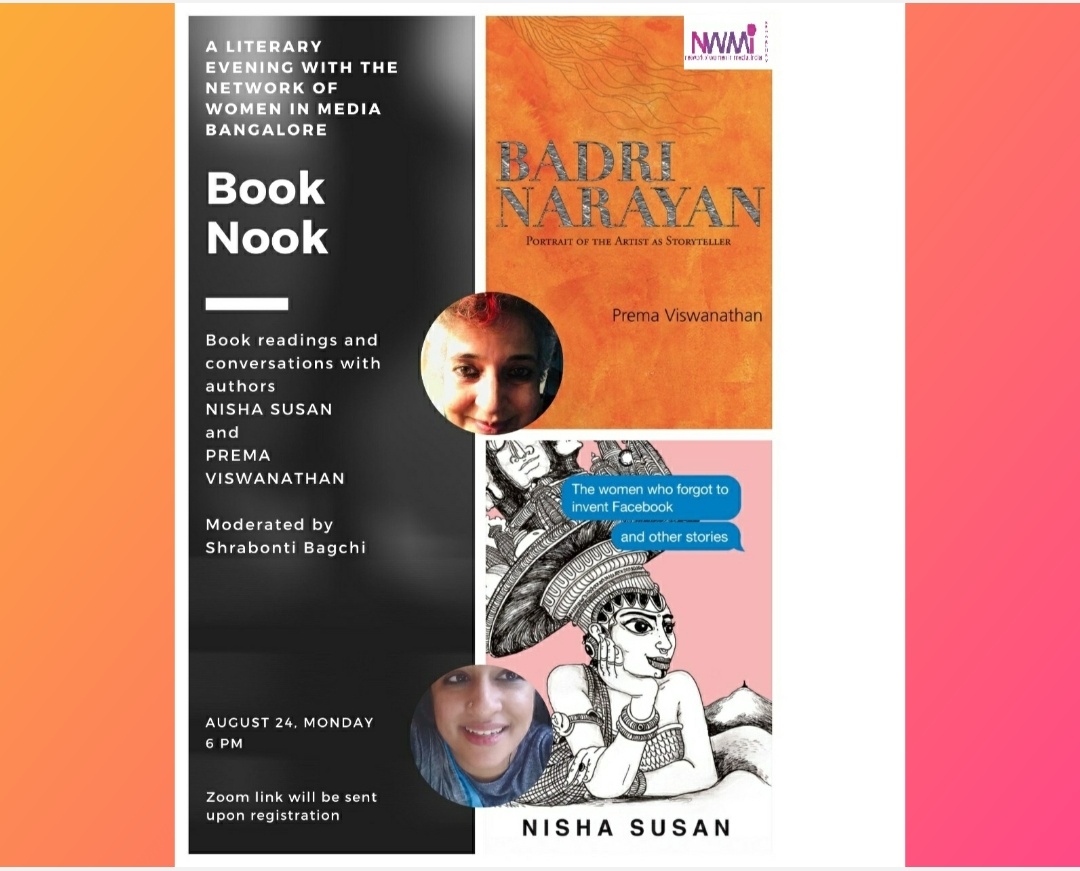

On a cool, Covid August evening, a literary webinar bridged socially distanced hearts and minds. Two completely disparate writers, Nisha Susan and Prema Viswanathan, shared ideas and extracts from their new books with 35 registered participants (network colleagues from across the country) during an online event hosted by the Network of Women in Media, Bangalore, on 24 August. Moderated by Shrabonti Bagchi, the discussion began with the two authors sharing reflections on the processes that led to the books, one fiction and the other non-fiction.

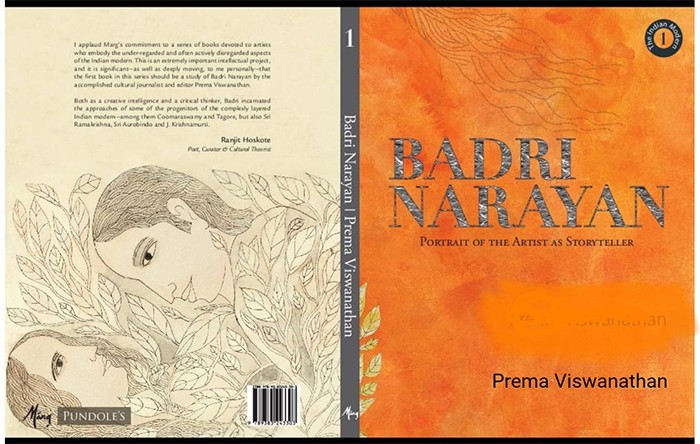

Veteran journalist Prema Viswanathan, author of Badri Narayan: Portrait of the Artist as Storyteller, has covered art and culture over two decades. Her book, co-published by Marg Publications and Pundole Art Gallery, is the first in a Marg series titled ‘The Indian Modern’. Although Badri Narayan passed away in 2013, she was able to persist with the book she had been working on since she had interviewed him several times over the years.

Veteran journalist Prema Viswanathan, author of Badri Narayan: Portrait of the Artist as Storyteller, has covered art and culture over two decades. Her book, co-published by Marg Publications and Pundole Art Gallery, is the first in a Marg series titled ‘The Indian Modern’. Although Badri Narayan passed away in 2013, she was able to persist with the book she had been working on since she had interviewed him several times over the years.

Prema talked about the veteran artist’s personality and creativity, explaining that despite not having undergone formal training in art, he evolved his own style, firmly locating his work within the Indian cultural milieu. She recalled that he never tried to be in the limelight, yet was confident and modern, even as his artistic language was steeped in Indian tradition and mythology. According to her, he was a voracious reader and a thinking artist even though he had not completed college education.

Badri encapsulated a modern sensibility, but without rejecting the past. He drew from the past everything that was salvageable, so that the past became a vocabulary for him, whether it was religion, mythology or allegory. What excited her was that Badri’s ecosystem was very non-hierarchical, putting all genders, flora, fauna, mythological and ethereal beings on the same plane. It was of special significance in a modern world torn by human callousness. He also looked at the multiplicity of religious narratives and the way they have seeped into the modern Indian consciousness, though he seemed to be closest to Buddhism.

Badri simulated the etching technique, borrowed from William Morris, giving a shadowy backdrop to his figures. In several of his paintings, women are at the centre and look at you straight in the eye, while men are at the periphery and look sideways.

As a character, Prema called him “shy” but also a bit passive aggressive. Although he was not assertive like his wife, he was quite single-minded in his pursuit of his artistic mission. Another of his passions was teaching. He melded the artist and the teacher for 16 years at the Bangalore International School. He also gave pride of place to Child Art and Tribal Art, pointing out that neither of these art forms is simplistic but both are simple, cloaking deep thoughts and hidden meanings. He also treated the child as a repository of intuition and insights.

Nisha Susan, columnist and founder-editor of The Ladies Finger, talked about the process of writing the short stories that have been published in the collection, The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook and Other Stories. Having grown up in Nigeria and Oman, she worked and wrote for a number of publications before she went on to launch The Ladies Finger. She said that she grew up in a household where everyone read and literary writing, too, was considered a normal activity. Her grandfather, particularly, wrote fiction and non-fiction as a near-full time activity after his retirement. She has been writing short stories for over a decade, but finally decided to publish the collection when the stories seemed to come together, thematically, around the Internet and technology. According to her, “Writing short stories is an ongoing pleasurable activity. In order to write stories, you have to be an ecosystem of enjoyment.”

Nisha Susan, columnist and founder-editor of The Ladies Finger, talked about the process of writing the short stories that have been published in the collection, The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook and Other Stories. Having grown up in Nigeria and Oman, she worked and wrote for a number of publications before she went on to launch The Ladies Finger. She said that she grew up in a household where everyone read and literary writing, too, was considered a normal activity. Her grandfather, particularly, wrote fiction and non-fiction as a near-full time activity after his retirement. She has been writing short stories for over a decade, but finally decided to publish the collection when the stories seemed to come together, thematically, around the Internet and technology. According to her, “Writing short stories is an ongoing pleasurable activity. In order to write stories, you have to be an ecosystem of enjoyment.”

The oldest story, ‘The Singer and the Prince’, was written 12 years ago, while she commuted to work in a train. The Internet is the central, important theme of her book, beginning with cyber cafes, which represented something like expanding worlds for her or, as she put it, like an “earthquake in my life at that point”.

While the books seem dissimilar, Prema highlighted some connections she perceived. Pointing out that many of the stories in Nisha’s book have a “sexual connotation, or effervescence, that is unabashed and unapologetic”, she said Badri’s art, too, is imbued with an unabashed, empowered sexuality, even though it is not in one’s face: rather, it is part of his ecosystem and he is comfortable with it.

According to her, both books also reveal aspects of their writers in the narrative. She said her own pet passions, preoccupations and predilections naturally enter her writing, although she took care to ensure that the book was authentic in its representation of Badri and his work.

Nisha affirmed that most of her stories included autobiographical elements or parts of tales she was told by friends. She said her attempt in the stories was to figure out what happened afterwards, or before, or on the side. According to her, some of the characters in her stories are completely recognisable, such as the friend who visited a spa that turned out to be a horrific weight loss institution. She said she often picked up a story that obviously meant something to a friend and then wove other threads into it, invariably putting something of herself into the narrative. For example, she said, a story she wrote five years ago was based on an incident relating to dowry shared with her 15 years ago, which had stayed in her head and raised all kinds of questions.

Nisha affirmed that most of her stories included autobiographical elements or parts of tales she was told by friends. She said her attempt in the stories was to figure out what happened afterwards, or before, or on the side. According to her, some of the characters in her stories are completely recognisable, such as the friend who visited a spa that turned out to be a horrific weight loss institution. She said she often picked up a story that obviously meant something to a friend and then wove other threads into it, invariably putting something of herself into the narrative. For example, she said, a story she wrote five years ago was based on an incident relating to dowry shared with her 15 years ago, which had stayed in her head and raised all kinds of questions.

Nisha’s breezy, light narrative voice is her actual one, unlike other writers who often adopt different voices in their fiction. According to her, storytelling is what she enjoys more than anything. So it is a propulsive force for her, motivating her to give various tales shape. She recalled that while most people narrate interesting and fun stories, they absolutely run out of juice when they are asked to write about their own experiences, “because the bizarre education system gets in the way.”

The evening ended with each author reading excerpts from the other’s book. Prema selected two stories from Nisha’s collection which dealt with different milieus in different narrative tones. Nisha quipped that her stories were “gossipy” even when they exhibited a traditional touch. According to her, there was a shift in her story when an “episode is over”, even when other things might happen.

Nisha chose to read a couple of excerpts from Prema’s book that dealt with the artist’s spiritual journey and his experience as a teacher. Prema explained that Badri’s subversion of hierarchies and the way he peopled his paintings with diverse life forms also spilt over into his writing, allowing for an osmosis between the writer and the painter. Most writers found it a pleasure to work with him, she said, as he would extend the narrative, not just replicate it.

The evening left participants with an underlying sense of having found interconnections – among the featured writers as well as between them and the audience. It also provided a glimpse of the cultural interfaces between fiction and biography, modern lifestyles and traditional culture.