By Supriya Unni Nair

Video editor : Jisha Elizabeth

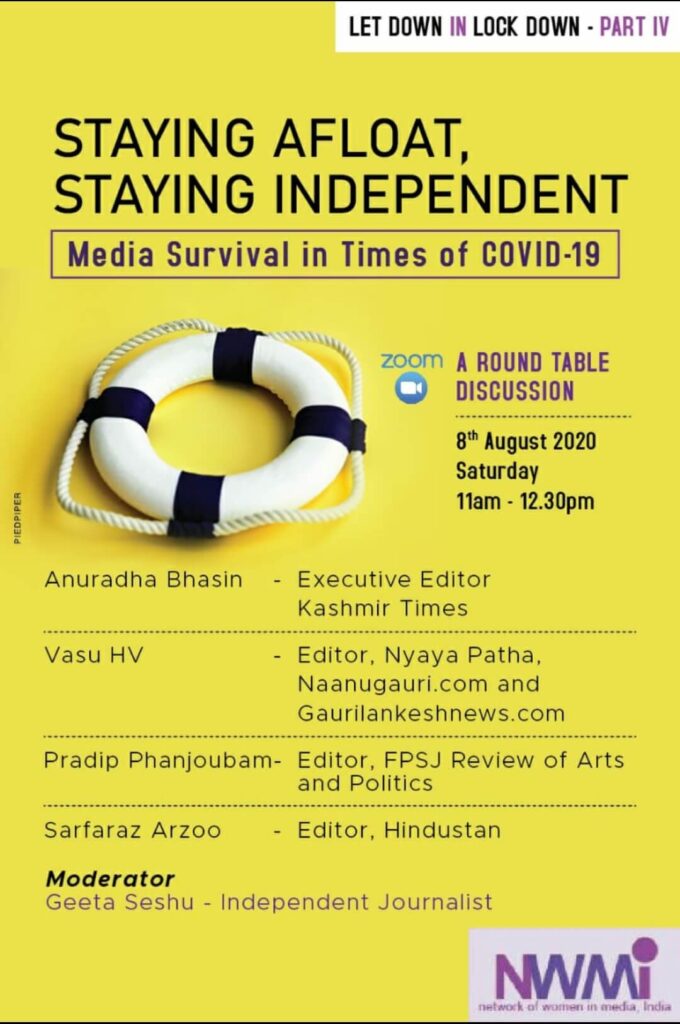

Panellists:

Anuradha Bhasin, Executive Editor, Kashmir Times, Vasu HV, Editor, Nyaya Patha, naanugauri.com, gaurilankeshnews.com ; Pradip Phanjoubam, editor, FPSJ Review of Arts and Politics; Sarfaraz Arzoo, editor, Hindustan; Meera K, co-founder and editor, Citizen Matters; Geeta Seshu, independent journalist (moderator).

Moderator Geeta Seshu began with an overview of the current grim situation faced by the media in the country. Several media houses have had to close, others have jettisoned print and transitioned into digital. News gathering budgets, which were anyway low, have shrunk even more.

However, she said, there is a silver lining. According to the website of Registrar of Newspapers for India (RNI), the number of new publications in 2017-18 was 3,704, while only 285 collapsed. According to her, this indicates that the desire to publish is still very strong in India. Geeta pointed out that there are still several valiant newspapers and news websites who keep trying to maintain their identity as “independent media”. Some have been around for almost 40 years, struggling to retain their integrity, and striving to resist political and economic pressures.

Kashmir Times: trials and tribulations

Anuradha Bhasin, Editor of Kashmir Times, explained that the story of their struggle began well before Covid-19 and traced it back to the beginning of the conflict in Jammu & Kashmir. She pointed out that there were challenges throughout, with the 1990s proving to be especially difficult for them. Over the past decade, they have been grappling with the problem of the State trying to choke the finances of newspaper organisations.

Anuradha Bhasin, Editor of Kashmir Times, explained that the story of their struggle began well before Covid-19 and traced it back to the beginning of the conflict in Jammu & Kashmir. She pointed out that there were challenges throughout, with the 1990s proving to be especially difficult for them. Over the past decade, they have been grappling with the problem of the State trying to choke the finances of newspaper organisations.

Jammu and Kashmir has very few business corporations, she said, and the economic indices are also not strong. So there is not much scope for commercial advertising. Because of this, the local media have always had to rely on central and state government ads as their major sources of income.

Anuradha pointed out that it was under these circumstances that the attempt to control media through advertisements began. She explained that there had never been a rational policy regarding advertisements and the distribution of ads was done in a whimsical way.

First ads placed by the central government’s DAVP (Directorate of Advertising and Visual Publicity), which were more substantial than state government ads, were stopped for certain newspapers. According to Anuradha, this changed later after the home ministry sent a notice to DAVP. However, Kashmir Times stopped getting ads in 2010; their English editions in Jammu and Srinagar as well as their newspapers in Hindi and Dogri were all affected by this stoppage.

As a result, the organisation could only hope to survive by cutting down on their scale of operations over the last ten years. This meant that staff size had to be reduced by 20 per cent. Circulation was hit, and their dependence on non-government ads went up, though the ratio of government ads to private is still 90:10. Somehow, with that small pool of resources, they survived.

According to Anuradha, for newspapers there is a huge gap between the cost of production and the selling price and they are therefore heavily dependent on advertisements. Apart from attempted control through the denial of ad revenue, Kashmir Times also had to deal with a number of legal tangles – so much so, she said, that one of the editors was perpetually sitting in court. In this situation, some staff left the paper because the organisation was unable to offer salary hikes or even pay salaries on time.

She said the last year (after the abrogation of Section 370 and related developments in August 2019) had been particularly bad. Whatever ads they had managed to secure were pulled out after she approached the court against the shutdown of communications, which made it extremely difficult for the media to function. This was the point at which the Dogri and Hindi editions were shut down. The English edition stayed afloat until Covid hit. The lockdown meant that hawkers could not even distribute newspapers.

Anuradha explained that although arrangements had been made for technical staff to stay at the press during times of conflict, it became very difficult during the pandemic because of the required social distancing and hygiene practices. As a result they had to shut down the print edition and continue with only the online edition.

According to Anuradha, the future is very uncertain. She noted and appreciated the fact that some of the staff had stayed on despite multiple challenges because they believed in the form of journalism and the values that Kashmir Times was built upon.

The digital route

Anuradha explained that digital platforms were suitable for them in this situation since this model requires less investment and has greater outreach. In a place like Jammu and Kashmir, where infrastructure is poor, this should have been the best way forward.

However, she pointed out, for the past one year there has been virtually no internet connectivity in Jammu, and smart phones have been rendered useless. People do not have access to dynamic websites because when connectivity was finally restored, it was restricted to 2G. According to her, most subscribers rely on mobile internet data and not broadband. In Kashmir, the internet was not available at all for six months and this resulted in several Srinagar-based newspapers shutting shop, while the web editions and e-papers were not able to function.

According to Anuradha, the January 10 verdict in her case did state that restrictions cannot be imposed for prolonged periods, but it did not specify what constituted prolonged periods. In May and June there were encounters in Kashmir Valley which resulted in the internet again being totally inaccessible. This naturally hit news gathering.

In addition, the climate of fear under which they lived made staff uncomfortable about pursuing certain stories. At one stage, it was very difficult to get reporters based in the valley to think of story ideas and discuss them. Staffers were not comfortable working out of the media centre either, and district correspondents had all but disappeared. Anuradha said that at one point they could hardly get any information from the valley.

The necessary constant interactions with people and officials became a huge challenge, she said, explaining that, unlike bigger media houses, they could not afford to send teams down for stories. To circumvent that, they picked up stories from the national media and used them as sources. They scanned social media for people who travelled to Kashmir and tried to pick up their voices. She pointed out that since people were scared to talk it was tough to approach them. Authenticating stories with officials was also a challenge. They were forced to compromise on quality as there was no way out, she said.

Revenue model

Anuradha said sourcing investment was difficult because of fears that it could invite charges of illegality. She explained that they have been shadow boxing all this time, and that crowd funding was the only way forward for them. They were also looking at funding agencies in India and abroad. However, she said, in her experience, many people do not want to be associated with anything that has the Kashmir tag.

The Lankesh legacy

Vasu HK, Editor of Nyaaya Patha (earlier Gauri Lankesh Patrike), naanugauri.com and gaurilankesh.com, echoed Anuradha’s observation that Covid was not the starting point for the challenges that independent media organisations in India have had to face.

He explained that the founder of Lankesh Patrike, P Lankesh, was very particular that they would not seek advertisements and be ‘at the mercy of the government’. He believed that the reader should pay for the content – whatever price they would pay for a coffee and masala dosa – and managed to make a profit despite not publishing ads.

Vasu pointed out that, ironically, while the price of coffee and masala dosa had gone up, that of newspapers remained low and it was difficult to sustain newspaper production. In addition, he said, newspaper distribution has been hit and they are now depending on subscriptions. Earlier sales from newsstands used to contribute substantially to revenue. However, Bengaluru saw a fall in the number of newsstands from 5,000 to 1,000. This, combined with high rentals for the stands, have hit the organisation’s revenues.

Vasu explained that they decided to go digital to overcome these hurdles. However, they faced problems even when they took that route. For example, until recently Google ads were not available in Kannada. According to him, they finally got access to the ads only when Google opened up ads in Kannada during the lockdown.

He said Facebook has been openly hostile to them, shutting down their website and Facebook page, citing ‘ technical issues’. Vasu thinks the blocking began soon after they carried exposes on a ruling party MLA’s scams in the state. FB ‘Insta articles’ had to be withdrawn as well. Vasu felt that the association with the name of the late Gauri Lankesh could have been a trigger.

Despite difficult times, he said, they managed to hire two new people to the team. He revealed that they had planned to hire more people but were unable to do so. Although people identify with the organisation as one related to their cause, just the cause is not enough to sustain the company, he said. Even if you go digital, at the end of the day you need a minimum number of staff to upload stories and maintain the website.

According to Vasu, they had plans to start crowdfunding along with MILAP. Subscribers continue to add to their revenue. The organisation is also taking part in a study, along with Azim Premji University and the Centre For Sustainable Employment. An application for funds from the Google News Initiative’s Journalism Emergency Relief Fund has also been approved. They also try to bring in some revenue by printing books. A combination of all these different routes of funding is what has helped them so far, he said, adding that they also plan to explore the specialisation/hyper local model in the future.

Global shakedown

Pradip Phanjoubam, editor, FPSJ Review of Arts and Politics (earlier editor, Imphal Free Press), pointed out that there is a paradigm shift in the business of media, and this is happening globally. The change is characterised by a marked migration of ads to the internet.

According to him, the days of print media are numbered. The electronic media may also be hit. Now we have 4G, he said, but when we have 5G it will be worse as whatever can now be done via direct cable would be done easily on the internet. Because of social media, ordinary people are uploading news events – so even the concept of breaking news has undergone a change and is no longer the monopoly of professional news sources, he pointed out.

Pradip is of the opinion that smaller, independent media organisations need to be prepared for the new realities. However, they already have their own, existing set of problems to deal with. Smaller newspapers have never had enough resources to be lavish about salaries, etc. – so the only way forward is to migrate to the internet.

Unique employee-owned model

Pradip described how a group of like-minded people got together to launch the FPSJ Review of Arts and Politics. Most of them have their own separate, sources of income but they were keen to express their opinion and the website was primarily a platform for that. This coming together resulted in a website that a team of employees owned and ran.

According to him, there were no overheads while launching the website. Their principle is that if they earn revenue from the website, it is shared, and if not, they do without. The organisation, which is six months old, is doing well, he said.

They also have a print edition which relies on newsstands for distribution, but this has been hit by the Covid crisis, he added.

About revenue generation, he felt that Google ads would only represent a small percentage of what was required and not reliable or sustainable as the main source of income. According to him, crowdsourcing and subscription models are the only way forward.

Print industry hit badly

Sarfaraz Arzoo, Editor, Hindustan, described Kashmir as “only a sort of laboratory” for India. According to him, Hindustan (an Urdu newspaper) and most other regional language papers are all in the same boat. He pointed out that the print media suffered losses of over Rs 4000 crore in the past four months and the amount is projected to cross Rs 16,000 crore in the near future.

He said he was looking for some assurance from the government that it would come forward to provide relief to the industry in this scenario, but what is happening is the opposite. He explained that he expected concessions such as cuts in General Sales Tax (GST) and import duty and an increase in government advertisements. However, the DAVP spend on ads is down one third, compared to what it was two years ago, when it was around Rs 600 crore per annum.

Sarfaraz pointed out the RNI figure of 285 media outlets closing down only applies to those who have actually reported closure. Many have just ‘closed shop and run’, he said, and have not been counted. He explained that since the current environment is seeing more ads flowing towards the digital platform, Hindustan had no option but to go digital, too.

According to him, their readership was dwindling as well. In places like Mumbai, the distribution network collapsed in the wake of Covid. Vendors were unable to transport newspapers as trains were not running. Eventually, he said, they will have to go looking for ads after they establish themselves online.

Sarfaraz feels the digital platform seems easier to manage as there is more accessibility on laptops and mobiles. He believes the future lies in crowdfunding.

According to him, all the newspapers should unite, raise their voices and seek help from the government.

He said he can confidently state that no one from Hindustan has been laid off. He explained that they have devised new ways to attract readers, especially among the youth. Understanding the psychology of the younger generation had paid off well, he said. He pointed out that the new digital platform has vastly increased their reach across the board.

Niche websites

Meera K, editor of Citizen Matters, explained that they are dependent on small grants, donations from High Networth Individuals (HNIs) and contributions from readers to sustain themselves. Their model has minimal expenses since it is a virtual organisation, she said. Citizen Matters was initially a for-profit organisation but later became non-profit.

According to Meera, cost of journalism is the biggest overhead. She explained that, in India, monetisation is made more difficult by the fact that the online ad model is not very mature. The returns are not very impressive or sustainable. When it comes to advertising, CPM (cost per mile) rates are very low compared to the rest of the world. To make things worse, during Covid, these went down even more.

Also, Indian news media has no access to foreign funds due to government policy. There are a lot of international grants available for niche topics but they are unavailable to the news media here. Corporates also seem hesitant about funding media, she said, even those specialising in niche areas and not political news. Under the circumstances small media depend on retail donors, said Meera. She explained that although donors can receive tax deductions for contributions to non-profits, the hardest part was to actually convince people to donate.

Motivation to go forward

Sarfaraz Arzoo credited the missionary zeal that his organisation believes in as the boost that keeps them trying to go forward. According to him, money should be and is just secondary. They believe they owe it to society, to their readers, to give them the best.

Pradip Phanjoubam said that it is his passion to communicate that has helped him carry on during difficult times. He believes that the innate desire to portray news as one sees it propels him and his organisation forward.

Vasu HV explained that, for him, the challenge is not just to journalism, but to the concept of democracy. Passion towards social change is what has pushed him forward. He said that, in a sense, we are all activists, and no organisation, no movement, can be successful without a proper communication and messaging mechanism. In this regard media, in collaboration with people, represent an essential tool.

Anuradha Bhasin believes free media is paramount for a healthy democracy. It is important to convey information, however little it may be, and – most importantly – to tell the truth. She said that even in this dismal and despairing situation, she and her team at Kashmir Times were crazily optimistic. “We are on the ventilator and we hope to revive,” she said, enabling the webinar to end on a hopeful note.

This webinar, too, saw a lively interactive session between the panellists and 48 participants.

To know more about other webinars in our “Letdown in Lockdown” series, visit https://nwmindia.org/initiatives/jobs-initiative/letdown-in-lockdown-jobs-initiative/