By Editors

This is a short note on the proceedings and discussion at the NWMM meeting on Khairlanji, Dalits and the media on November 28, 2006, at the Press Club, Mumbai.

Panellists:

- Dr Anand Teltumbde, a writer, activist and part of the human rights movement. He was part of a fact-finding team that went to Nagpur, Amravati and other places to look into the harassment of those who protested after the Khairlanji incident.

- Rakshit Sonawane, a senior journalist with the Indian Express who has written critically on issues concerning human rights.

- Yogesh Pawar, a journalist with NDTV who covered the Khairlanji incident and its aftermath for television and has consistently covered such issues in the past.

Moderator:

Ranjit Hoskote, assistant editor, The Hindu

Ranjit Hoskote, in his opening remarks, mentioned that even though the Khairlanji incident took place on September 29, the mainstream media ignored it for a long time. Only when the protests against the brutal killings moved from being peaceful to agitated in places such as Vidarbha, Amravati and Yavatmal did the media take note of the horrific incident. He said that he felt that large parts of the mainstream media tend to treat the Dalit issues as a speciality — like marine biology or some other specialisation and not as something that affects a large percentage of our population. They do not cover Dalit issues unless there is an incident or the coverage revolves around reservations, law and order problems or social fragmentation. One of the reasons for this, he suggested, could be because the media is dominated by the upper castes.

Anand Teltumbde said that he had not visited Khairlanji but had looked at the fallout of the incident. All the reporting in the media was about the basic incident. In terms of brutality, it stands as a pure case of a Dalit/caste atrocity. One of the reasons was the Bhotmange family were above average in their political consciousness. They were a typical Ambedkarite family who were educated, and had five acres of irrigated land. But the Khairlanji gram panchayat refused to register them as residents of the village. As a result, they could not build a pucca house. He said that as the entire village had participated in the attack on the Bhotmanges, the crime automatically qualified to be registered under the Atrocities Act. But the police have suppressed all evidence and there has been a systematic attempt to destroy evidence. The role of the state had been exposed through this incident, he said, and he felt that the real culprit was the state.

On the fallout post-Khairlanji, he spoke of the November 14 peaceful demonstration of around 15 to 20,000 people, led by women, in Amravati. When people were returning after the demonstration, the police lathi-charged and fired 15 rounds. As a result, one boy died. Altogether six rounds hit people, all of them from the back. Even those injured in the lathi-charge showed how brutal it was. In Yavatmal, the police response was even more brutal. There was an attack on a Dalit basti. Chappals were thrown at the Ambedkar statue. At night, 100 to 200 police entered the basti and 50 youth were taken in. Even someone like Pramodini Ramteke, a well-known activist, was picked up at 3 a.m. There were no women police present. She had to put up with verbal and physical abuse of a kind she had never experienced before. This vehement action against protesting people by the state needed thorough investigation, he said.

Senior journalist Rakshit Sonawane asked why there was a delay of a month before political parties and the media woke up to the Khairlanji massacre. He also said we need to look at the pattern of coverage after that month. Post-September 29, for almost a month, there was no serious media reportage. It was treated as a routine crime incident. Only after the violence in Nagpur did various factions of the RPI wake up as also the English media.

Dalit leaders were busy observing and celebrating two major functions: October 2 organised by the Diksha Bhoomi Smarak Samiti of R. S. Gavai, now Governor of Bihar, and October 14, fifty years since Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism. All Dalit leaders visited Nagpur for these two functions, yet none of them mentioned Khairlanji. Why? Rakshit suggested that these leaders might have been compelled to remain silent on this issue because “Dalit leaders and Dalit parties are servile to mainstream political parties and their leaders”.

The traditional Dalit leaders, he said, did not organize the first protest in Nagpur. In fact, a lot of things began moving when educated Dalits, who do not follow the diktats of these traditional Dalit leaders, mentioned the atrocity in email listservs and on web blogs. He said that the kind of reporting that was expected was not done and that most reports were about Dalits coming out on the streets and the police bashing them up. There was less reporting of the incident and more on the Dalit response to the incident. The reason for some of this is the inherent caste prejudice that is deeply rooted in the mind of a typical Indian and the Indian media also represent this mindset. It is difficult to expect justice until more Dalits come into the media. He said the vernacular press was equally bad in its coverage of caste issues and here groups of journalists were held together by caste, region, community, and any other reason except professional reasons.

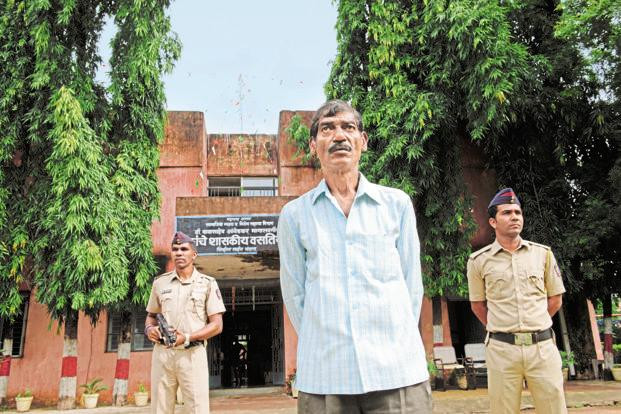

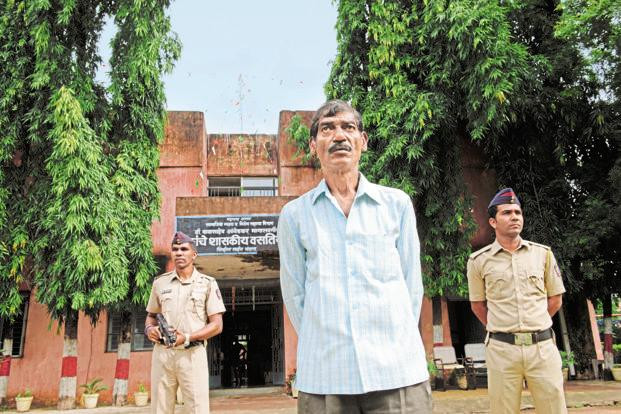

Yogesh Pawar of NDTV said that the initial response of television was to treat it like a crime story — “Dalit family massacred over a land dispute”. It was only when he spoke to other Dalits in the village that he got a sense of the larger story. One woman said to him, “She (meaning Bhotmange’s murdered wife) did not how to live by the rules.” While the story moved from being a crime story to being a law and order story, it was treated less as a caste atrocity story. He also spoke of how Bhaiyalal Bhotmange had been taken around by activists and political parties to repeat his story. It was pathetic to see him paraded like this, he said, and asked whether this helped the cause.

Even as the discussion began, we got a message that Bhaiyalal Bhotmange was next door and before we could decide what should be done, some activists brought him in. The flow of the discussion, which had just begun after the three speakers, was broken. But on the other hand, as he was in the area, it would have been extremely difficult to refuse to let him come as we were discussing Khairlanji. Bhotmange asked the journalists to ask him questions and then said that he had met R. R. Patil and demanded that the policemen involved be arrested. One of the other activists from the Bhandara district thanked the press for highlighting the issue and said that this was their only hope of getting some justice.

After Bhotmange and the political activists with him left, a discussion followed in which many members of the media, especially from the language press as well as human rights activists, participated. One reporter from a daily Marathi newspaper admitted that coverage of such incidents in the language media was no different than that in the English-language newspapers. Someone else mentioned that most often the media merely reproduces what the government or police tells them — which made someone remark that “most crime reporters were police stenographers”. Journalists talked about the space for meaningful reporting shrinking in the mainstream media and attempts by some of them to hold on to such spaces. Mr Teltumbde said that what needs urgent coverage now is the violence against Dalit protesters post the Khairlanji massacre — in many cases where peaceful protesters have been labelled as “Naxalites” they are now being harassed by local police and have had to run for cover.

November 28, 2006