By Swarna Rajagopalan

(Guest Post)

With Assembly elections in five states just a few weeks from now, election fever is setting in. This short post is a reminder of what it would take to convince women that political parties care about their rights and welfare.

Ensure better representation and better campaign support

In September 2023, the Indian Parliament passed the long-demanded Women’s Reservation Bill or Nari Shakti Vandan Abhiniyam (Constitution (128th Amendment) Bill, 2023), promising the reservation of one-third of legislative seats for women, albeit with applicable terms and conditions such as a new delimitation of constituencies following an already-overdue census. The crudest indicator that a party’s recent Parliamentary vote for the women’s quota was not empty performance would be to nominate more women without waiting for the Bill to take effect and ensure a more gender-representative slate of candidates without further delay. I would say 50% but given the appalling numbers would press for any absolute increase.

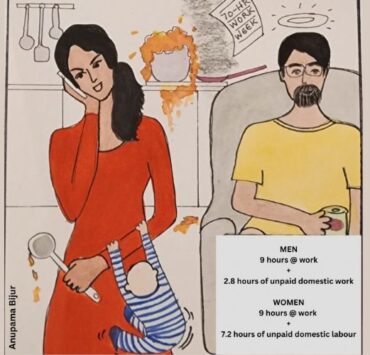

Nomination is not enough. Women struggle to raise money for campaigns. Patriarchal family structures also mean they have more responsibilities within the home and less support as they step outside its threshold. Their campaigns attract fewer volunteers and supporters. If a party wants to signal its support for gender equality, it must extend greater support to candidates from marginalised groups and make sure its star campaigners do not miss their constituencies.

Shun candidates with records of hate speech

As election campaigns gather momentum, candidates and campaigners become less circumspect. A party that is genuinely concerned about gender equality and respecting human beings would be quick to reprimand and punish those party members whose public statements disparage, mock or abuse other human beings on grounds of gender, community, ability or sexuality. They should not look away hoping no one notices. It would be too much to hope that they would withdraw an offending candidate at this stage (though this should be a disqualification under the Code of Conduct) but they should certainly pull offending campaigners off the circuit.

Blacklist and debar candidates accused of sexual and gender-based violence

Sexual and gender-based violence is pervasive and is perpetrated across an individual’s lifetime. Parties should automatically and publicly blacklist those members accused of crimes ranging from prenatal sex selection to rape and molestation to sexual harassment and assault to domestic violence and elder abuse (see Prajnya’s Gender Violence in India reports for the different types of violence that fall into this category).

The standard of ‘innocent until proven guilty,’ observed in the breach in so many political contexts, is applied generously to gender violence accused when they are influential men or men with influential connections. A party genuinely committed to gender justice would impose a bar on those accused or charge-sheeted for such crimes until they are officially acquitted. Only then should they be eligible to stand for elections. Given court delays in India, to grant them the benefit of the doubt is to signal that you do not care about their victims, almost invariably women and too often also belonging to marginalised and extremely vulnerable groups.

Adopt gender transformative agendas in election manifestos

We have come far enough that all party manifestos feel obliged to include a section on ‘women empowerment.’ For now, let us not debate what that means. Promises in this section usually relate to safety and livelihoods. The former may include measures like CCTV cameras in public spaces and All Women Police Stations. The latter might include employment promises, educational and vocational training assistance, credit for entrepreneurship, cash transfers or gifts of useful amenities like bicycles, sewing machines or gas connections and free bus travel, to list a few examples.

Each of these has its utility and importance. What is problematic is that they reveal a view in which women are not citizens with rights and entitlements but creatures to be protected and patronised. Women are daughters, sisters, wives or widows, always related to benevolent male authority figures. They are stereotyped as helpless and in need of rescue. They must be lifted up and empowered.

A party that cares about voters of all genders, about gender equality and gender justice would regard women, and members of other gender minority groups, as individuals with aspirations and ambitions beyond safety and survival. It would recognise that their interests and talents might extend to non-stereotypical occupations such as tractor repair or stock market trading. Investment in inclusive and gender responsive urban planning or public design rather than surveillance may better guarantee safety. Such a party would also invest in the institutional infrastructure provided for gender justice—Local Committees to hear workplace harassment cases; better-resourced Protection Officers; expedited court procedures for gender violence cases; and the mandate in virtually every gender justice law to create awareness around rights and support services. A party genuinely concerned about supporting victims of violence would take a serious look, in consultation with experienced service providers, at the state of shelter services around India.

Something-that-looks-like-feminism is fashionable in 2023. What our politics lack is a genuine concern for gender equality as a human right, an enabling condition for a better life for all of us. Feminist scholar Cheris Kramerae defined feminism as “the radical notion that women are people.” Some of our politicians get this but our political class and political parties have a long way to go. Therefore, this post is as much a wishlist as it is intended to be a memo to political parties and leaders as campaigns for the upcoming state Assembly elections get underway.

Swarna Rajagopalan is the founder of Prajnya which drafted the Gender Equality Election Checklist. A political scientist by training, she has been blogging on the gender politics of Indian elections on Prajnya’s PSW Weblog and for NWMI.