By Urvashi Sarkar

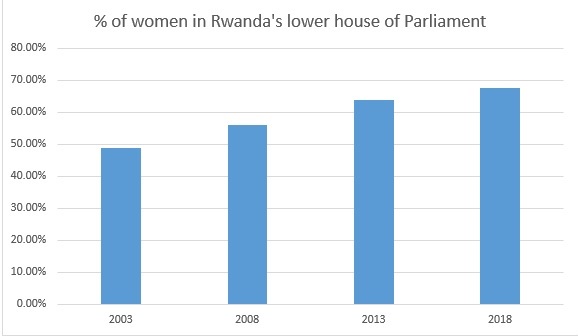

Rwanda garnered international attention in 2003 with a heartening development – 48.75% of the representatives elected to the lower house of the Rwandan Parliament were women. In 2008, women constituted 56% of the lower house of Parliament and the proportion increased to 64% in 2013. In September 2018, the country made headlines yet again, when women won 67.5% (over two thirds) of the seats, setting a new world record for women’s representation in Parliament.

Source of figures: http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2018/8/feature-rwanda-women-in-parliament

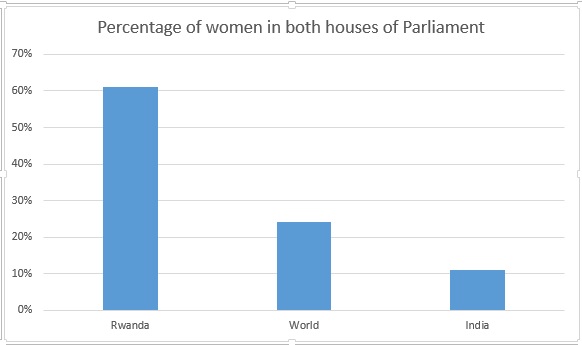

As of October 2018, women constitute a global average of 24% in both houses of Parliament, according to data compiled by the Inter-Parliamentary Union. For India, the last national elections of 2014 resulted in 11.8% of women in the Lok Sabha (lower house of Parliament) and 11.4% in the Rajya Sabha (upper house).

Source of figures: Inter-Parliamentary Union

In October Rwanda also became the second African nation in a week to announce a gender-balanced Cabinet, with women making up 50 per cent of its members. Ethiopia led the way a few days earlier.

A little less than two decades ago, Rwanda was devastated by a genocide in in which more than 800,000 people died. One of the consequences of the 1994 genocide was the altered gender demographics of Rwanda. Although more than 250,000 women were victims of sexual violence, a larger number of men died, left the country, were missing or imprisoned. The women who were left behind had to play an important role in the reconstruction of the country.

Prior to the genocide, women lived in an oppressive milieu. Writing in ‘The New Times’ , Rwandan political analyst Ladislas Ngendahiman noted that women were considered second class citizens, neither allowed to inherit land nor pursue formal education. In the 1990s, women constituted just about 18% of Rwanda’s Parliament members.

In a 2008 paper on ‘Women in Rwandan Politics and Society’, authors Claire Wallace, Christian Haerpfer and Pamela Abbott describe measures which encouraged women’s participation in politics, such as Rwanda’s 2003 constitution, which gave women a 30% quota in all decision-making organs, a Ministry of Gender (the first of its kind in Africa) and ‘The Inheritance Law’, which aimed to give women access to their own property and to enable them to conduct business and enter into contracts in their own right.

Women’s participation in politics was further enabled through the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion, the Rwanda Women Parliamentarians Forum, the National Women’s Council and the Gender Monitoring Office. A five-tiered system of women’s councils, too, played an important role in facilitating women’s participation in development initiatives from the village to national levels.

The strong numbers of women in Rwanda’s political decision-making has had an impact on women’s lives. UN Women notes that women parliamentarians have helped bring in revisions in the Civil Code which now provides equal inheritance and succession rights for men and women, and mandates the elimination of any form of discrimination in the laws that govern political parties and politicians. Women parliamentarians have also initiated labour laws that guarantee equal pay, legislation providing equal rights to access and own land, as well as laws aiming to end gender-based violence, harassment and discrimination at work.

Undoubtedly, Rwanda’s achievements are impressive. It has won global recognition for its transformation after 1994, especially in the area of healthcare reforms, including the significant reduction of infant mortality and an increase in life expectancy. Its efforts to promote gender inclusive politics has won it many plaudits, and all countries, especially India, can learn from Rwanda’s policies in this regard.

However, critics of the Paul Kagame government have highlighted the targeting of women activists and politicians such as Diane Rwigara and Victoire Ingabire. The pan-African newsletter Pambazuka noted: “Ingabire and Rwigara attracted Kagame’s wrath simply by declaring their intentions to run in Rwanda’s sham Presidential elections of 2010 and 2017. In both elections, Kagame ran unopposed, receiving the share of votes he precisely wanted: 93% and 99% respectively. Ingabire has been in jail since 2010 on trumped-up charges of revisionism, genocide ideology and supporting armed rebellion against Kagame’s regime. Rwigara, her mother, and siblings have recently been detained, their property destroyed or confiscated, in a very shameful and blatant display of Kagame’s inhuman behavior.”

There are concerns that women’s empowerment in Rwanda has benefitted only those who are economically well placed. Poor persons, such as women street vendors, are said to be subject to cruelty from Rwandan police. In this context, The Rwandan newspaper wondered: When would all Rwandan women from all walks of life benefit from their majority in parliament?

In an interview to The Guardian, Diane Rwigara, who was barred from running for President in 2017, stated that the Rwandan Parliament was a little more than a rubber stamp and, although women occupy senior positions in government, they do not possess real power.

Press freedom in Rwanda is a matter of concern, too, with the country ranking 156th of 180 in the 2018 World Press Freedom Index.

Defaming or insulting the President can result in prison terms between five to seven years and cost up to 6860 euros in fines, as per the country’s new penal code. Female journalists such as Agnes Nkusi Uwimana and Saidad Mukakibibi have also been arrested for their work. Anjan Sundaram’s book ‘Bad News: Last Journalists in a Dictatorship’ describes the climate of great repression that journalists work under in Rwanda. It also decodes Paul Kagame’s ‘carefully choreographed’ image and policies, which enjoy great support from his western backers. The Kagame government is known to suppress political opposition, with opponents being subject to threats, arbitrary arrests, assassinations and forced disappearances.

Given the heavy consequences for political opposition, Rwanda’s parliamentarians have had limited room to bring about change. Nevertheless, they have passed important legislation on gender based violence, legalising abortion in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest and where continued pregnancy endangers the health of the mother or the foetus, besides mandating 12-week maternity leave.

The road ahead for Rwanda is not an easy one. Using their limited available power, women in Rwandan politics have to work to ensure that women from all classes and sections are able to access and reap the benefits of empowerment, tackle deep socio-economic inequalities, and fight for a open, inclusive and democratic political society.