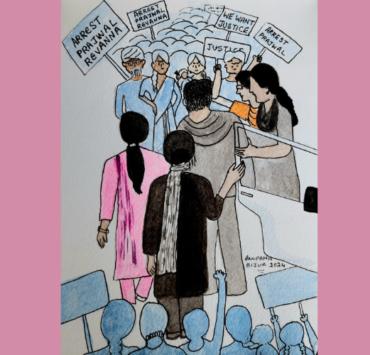

By Jyoti Punwani

Women participated enthusiastically in campaign meetings ahead of the fifth phase of the election in Maharashtra

Women voters are, often, not as accessible as are men, and few reporters, myself included, seek them out. This time however, I didn’t have to.

One reason was the manner in which Muslims in Mumbai took it upon themselves to campaign for the INDIA coalition (Indian National Developmental, Inclusive Alliance). Women became an important focus of their campaigns. At a meeting late in the evening, comprising mostly Muslims, held just before the close of campaigning ahead of Mumbai voting on 20 May, women outnumbered men. Organised by the Jan Parivartan Party, a fledgling political party based in the Mumbai suburb of Jogeshwari, the meeting was attended by women from the area’s slum settlements.

Jogeshwari East, where the meeting was held, has a history of communal riots in which the undivided Shiv Sena and the BJP played a major role. These include the post-Babri Masjid demolition riots of Dec 92-Jan 93. In fact, a major incident in which 6 Hindus (all but one of them women and children) had been burnt alive occurred not far from the venue of the meeting. According to the report of the Srikrishna Commission of Inquiry into the 92-93 riots, the Radhabai chawl incident was exploited by the Shiv Sena to create a “Hindu backlash” in January 1993, in which Muslims were targeted across Mumbai. Given this, it was significant that the meeting was held in support of the Uddhav Thackeray-led Shiv Sena candidate, Amol Kirtikar of the INDIA coalition. The candidate’s father Gajanan Kirtikar, had been named in the Srikrishna Commission as having led a morcha to the police station without permission. The morcha, while returning, attacked Muslims, their property and a masjid. Gajanan Kirtikar was charged with rioting, and acquitted in 2008 by a special court.

Two women I spoke to at the meeting had been children when the riots took place. They were firm in their assertion that it was necessary to put those riots behind them and vote considering the current reality. “Inflation is killing us, but all that the BJP does is talk about Hindu-Muslim,” said Husne Jahan. “This talk will affect our children. We should look at their future, not sit back clinging to our memories of past riots.”

Syed Nazneen, an office bearer of Jan Parivartan Party, said that both democracy and the Constitution were in danger. “Those riots affected Jogeshwari, but the politics of hatred being practised now affects the entire country. We have to support the INDIA coalition,” she said.

In the Mumbai North West constituency, both candidates were from the two factions of the Shiv Sena. The symbol identified with the Shiv Sena, the bow and arrow, had been given by the EC to the breakaway faction led by Eknath Shinde, forcing the Uddhav Thackeray-led Sena, part of the INDIA coalition, to adopt a new symbol: the torch or mashaal.

The speakers, all men, exhorted the women not only to vote on 20 May, but also to make sure the men of their family did so. “Don’t stay back making naashta (breakfast) for them. Please do your household chores after you vote,” said one speaker.

The chief guest that evening, former Congress Rajya Sabha MP and Maharashtra minister Husain Dalwai, expressed his happiness at presiding over “a rare political meeting, in which women outnumber men. That makes me happy, because women always stand with the truth.”

The meeting, like many others held in Mumbai before the city voted, exposed the hollowness of the stereotype of the “poor, backward Muslim woman”. At an interaction between candidates and young Muslims, a teenager aspiring to sit for the UPSC exams expressed her fear of being discriminated against. Unable to pay her fees, she had been prevented from appearing for a test in school. “My teacher asked, ‘You Muslims are all like this; why do you come to our schools,” she said, adding that her younger sister had faced the same taunt. It is unusual for a young woman to share such a humiliating experience in a hall full of strangers.

At the same meeting, a young Muslim woman said she was proud to be the only woman working in her NGO on education and health in her slum. “We educate women on menstrual hygiene,” she declared to a hall full of young men and women. “An international survey showed that lack of access to menstrual hygiene is a major cause of death of women,” she said, without a trace of embarrassment.

On the other side of the city, in Mumbai’s historic Shivaji Park, women had gathered for the final NDA campaign rally. Many of them had been bussed to the venue by the BJP, but were unwilling to wait for the PM to arrive. “We have to go home and cook dinner; in this weather, it would have spoilt had we cooked it before leaving,” a few of them said. “Tell Modi we waited,” an old woman said to me as she left. Surprisingly, even after Modi started speaking, the women kept leaving.

The Muslim women present were conspicuous in their black burqas. Since 2017, the colour black has not been allowed at the PM’s rallies; one woman complained that her husband had been sent back since he wore a black shirt. But for obvious reasons, the BJP wanted the black burqas to be noticed.

In contrast to these women who’d been brought in buses were those who’d come on their own, some in twos, some alone. Their aim was to see and hear the PM in person. For a woman to attend a political rally on her own, knowing that thousands of people are expected, is rare, and a testimony to how safe women feel in Mumbai.

One group of women voters I met, all Hindu, were defined by their gender not their religious identity. These were the ASHA workers, women who are the link between government health schemes and the labhaartis that the PM talks about. Tasked with distributing voter slips and checking electoral rolls, though this was not part of their duty, they had little time to follow election news. Some didn’t even know who their candidates were. All they wanted from their future MP was a willingness to help them solve the many problems they faced in dealing with the government, from wage arrears to not being considered regular government employees despite being on call 24/7.

Voting for the 48 Lok Sabha seats in Maharashtra was held over five phases from 19 April to 20 May. While they participated enthusiastically in campaigning, whether women turned out in greater numbers on 20 May is yet to be known. Overall, Mumbai’s six constituencies recorded a turnout of 52.38%, with the Mumbai North West constituency recording 53.67 per cent, a marginal drop from the 54.37 per cent it recorded in 2019, according to a report in The Indian Express.

Jyoti Punwani is a Mumbai-based journalist.

Edited by Shalini Umachandran