By Shikha Mukerjee

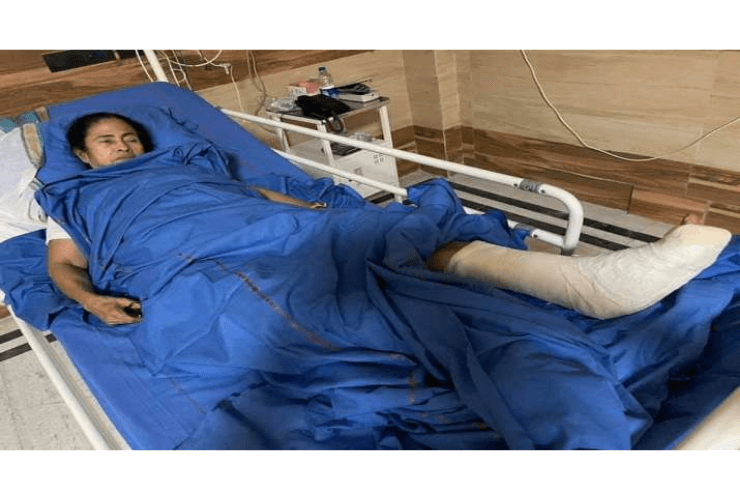

“Indecent, politically irrelevant and gender illiterate,” is the succinct assessment of a distinguished feminist scholar in Kolkata about the reaction of the political opposition and the media to the injury suffered by Trinamool Congress founder and leader, and West Bengal Chief Minister, Mamata Banerjee, on March 10.

Regardless of whether the injury was an accident or an attack engineered by opposition parties to immobilise Banerjee, as she alleged, there is no dispute, except in the minds of her challengers, that she suffered physical injury: that on the night of March 10 she was in serious pain and experienced genuine trauma. By criticising or dismissing her pain, questioning her injury, and mocking her management of it even as she struggled to overcome the physical constraints of being wheelchair bound, with a foot in a splint, the political opposition has revealed the depths of its lack of empathy as well as its gender illiteracy.

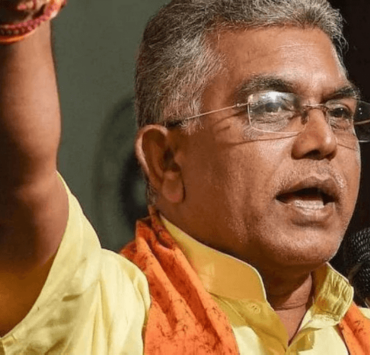

That the opposition has also exposed its illiteracy with regard to how fractures, torn ligaments and displaced bones are treated in the 21st Century is also significant. For the Dilip Ghoshs and Adhir Chowdhurys of West Bengal, the plaster cast appears to be the only possible medical response to a serious foot injury.

The targeted attacks that focus on the gender and body of the only woman Chief Minister in India currently are politically irrelevant. A Chief Minister is not defined by her gender; she is defined by the office she holds – just as the Prime Minister is not defined by gender (of Indira Gandhi it used to be said that she was the only man in the cabinet).

The level of political attacks on Banerjee touched an all-time low after March 24, when the state president of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Dilip Ghosh, said at a public meeting, “Plaster has been cut, there is now a crepe bandage, and [she] keeps raising her leg and showing everyone.” He then went on to add, “If [she] has to keep her leg out, then why wear a sari, [she] could wear a pair of Bermudas instead so that [it] can be seen clearly.”

Because the local media, especially the Bengali media, has played down the story of his objectionable comments, an emboldened Ghosh followed up his heckling of his political opponent by declaring at another public meeting on March 25: “Mamata Banerjee is the Chief Minister of Bengal. She should respect Bengal’s culture. A woman in a saree showing her legs repeatedly is not Bengal’s culture.”

Bengali culture, which the BJP has supposedly sworn to protect, is not about modestly covered women submissive to patriarchy. It is better defined by Prakriti in the form of Kali going on a rampage to the point where she tramples her lord and master, Shiva, underfoot. The image of the dark visage of the goddess, clad in a skirt of human skulls and dismembered limbs, with absolutely no deference to patriarchal notions of modesty, is the defining avatar of the female, fully empowered and totally in control. As a local variant of the Devi, the Bengali Kali is seen as an unstoppable force. In any case, Mamata Banerjee, with her obsessive habit of minimising any exposure of her body, can hardly be faulted for immodesty, whatever Dilip Ghosh may like to imply.

It is unfortunate that a bunch of women leaders belonging to the Communist Party of India [Marxist] (CPI[M]) have, surprisingly, added to the gibes by suggesting that the sole female chief minister in India at present is “kicking people in the face” – just because her injured leg is propped up when she addresses public meetings.

Local media responses to the physical injury that Banerjee evidently suffered has been strangely unprofessional. Instead of exerting every muscle to find out the exact nature of the injury, regardless of whether it was an accident or an attack, the news media have ducked their responsibility and restricted their role to quoting the opposition on the incident and its aftermath.

It is, therefore, unsurprising that when Ghosh made his unacceptable remarks on March 24 and 25, the media, especially the local language media, went out of its way to pretend that nothing much had happened. Media – both print and television – appear to be in denial, making his uncivil behaviour invisible by neither reporting on it critically nor asking women, including feminists, what they feel about the incident and reactions to it.

Given that this would no doubt be standard professional conduct if such an incident were to happen anywhere except in West Bengal and to anyone except to a female Chief Minister, the complicity of the media as an institution by maintaining what amounts to a studied silence on the insulting remarks is an unacceptable dereliction of duty.

The specific manner in which Banerjee has been heckled could well be seen as falling within the definition of sexual harassment in the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, as well as the Supreme Court of India’s definition of what constitutes such harassment. Article 1(3)(2)(iv) describes harassment in the workplace as “interference with her work or creating an intimidating or hostile work environment” and Article 1(3)(2)(v) includes “humiliating treatment likely to affect her health or safety.” Dilip Ghosh’s public utterances are not innocent remarks; they are loaded with innuendo. Of course, it is not clear whether politics in general, and election campaigns in particular, would be considered a “workplace” under the law.

The entirely intended sexism of the political class, minus Banerjee, became evident with the first reaction to the injury, from Adhir Chowdhury, the state President of the Congress party, who was removed from his responsibility as the party’s leader in the Lok Sabha. He raged against Banerjee for faking the injury, creating a “drama” and playing the victim card to gather sympathy for her electoral battle in the Nandigram constituency. Nandigram was once a TMC stronghold but the BJP was able to enter it recently thanks to the defection of the sitting MLA, Suvendu Adhikari, from the former to the latter in December 2020.

Till March 24, and Ghosh’s remarks, the BJP’s reaction matched that of the Congress. The party’s state president maintained and continues to insist that Banerjee’s injury was fake. To prove that he is right and trash her credibility, he has repeatedly drawn attention to the plaster cast that was removed from her foot within two days of the injury.

The video recording of his apparent obsession with Banerjee’s usually sari-covered legs has gone viral. Yet the media have barely reported what amounts to the sexual harassment of a woman who happens to be the Chief Minister and is also the founder and leader of a party that appears to be giving the BJP an unexpectedly tougher fight than the Sangh Parivar had probably anticipated.

To repeat, every day, the crass personal attacks by an array of men in leadership positions in the BJP, the Congress and the CPI(M), as the media has done for two weeks, points to the pent up “frustration” of the entrenched patriarchal order while dealing with a woman leader who is not weak – not even when injured – and who is capable of fighting a tough election battle that challenges the opposition to fight back. Instead of ferreting out medical reports that would confirm or deny the nature and extent of the injury, the media have instead allowed opposition leaders to persist in questioning Banerjee’s credibility without providing an iota of evidence. In doing so the media (including print, television, digital and social media content creators) have put on display the gender illiteracy and bias that pervades the profession, especially in terms of news gathering and reporting.

By buying into the narrative of the political opposition on Banerjee’s injury, the media – both regional and national – have revealed that reporting on women’s injuries reflects the inbuilt biases of societies across the world with regard to women’s experience of pain, no matter what the cause of the pain. Women who suffer injury are widely believed to be “hysterical” and so out of control that they exaggerate both the injury and the pain caused by it. Studies across the world show that women, as well as minorities, who seek healthcare for injury or pain are not taken seriously even by doctors and the medical system.

The prejudice is evidently so strong that governments and research organisations are working on the problem to find a way of delivering “equitable treatment” to female patients. According to a review of literature on gender bias in health care and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain, “Gendered norms about men and women with pain, present in research from different scientific fiends, illustrate prevailing hegemonic masculinity and andronormativity in health care… Awareness about gendered norms and that they can lead to a consolidation of the dichotomous depiction of men and women is important, both in research and clinical practice, in order to counteract gender bias in health care and to support health-care professionals in providing more equitable care.”

It is evident that hegemonic masculinity among health care professionals leads to pervasive social and cultural biases. For the media, recognising bias and working to actively counter it is fundamental to the ethics of the profession. The instance of Mamata Banerjee’s injury and the treatment of it by the media, amplifying without further investigation the allegations of the political opposition, represents a professional and ethical failure.

During elections, the connect between the media and the voter becomes intense, with information filtered and disseminated through visual images, in print and on television, through digital platforms and social media. For the media to uncritically and without independent assessment amplify the obvious political agenda of the opposition with regard to Banerjee’s injury and pain is to betray the journalistic principles of accuracy and fairness.

The possible trauma experienced by Banerjee has never been part of the media conversation about her injury. To make matters worse, no exploratory conversation with doctors, medical experts and trauma specialists about her injury is reflected in media coverage of it. The only actual information that has been available is from the brief official briefing by the hospital to which she was admitted.

To fulfil its responsibility to challenge power and inform the public of the antics of the powerful the media needs to guard against turning into a collaborator of the political opposition. In this case there is not even any underdog that the media can morally claim to be defending; the opposition to the incumbent is just as powerful and, in fact, clearly expects to become even more powerful should it succeed in defeating the party in power.

The aggressive response of the opposition in West Bengal to Mamata Banerjee’s injury underscores the fact that, far from becoming politically vulnerable due to the injury, she may have become even more politically formidable. The daily schedule of multiple public meetings for which she is wheeled up a ramp to the stage, where her foot is propped up on a stool, seems to have given voters even more reason to attend in large numbers as a show of solidarity. Her vulnerability appears to have boosted her popular appeal, especially among women.

That her physical vulnerability may have increased her popular appeal is something of a paradox. Other political leaders in other parts of the world who have suffered injuries or health issues during elections have faced a barrage of questions from the media about their subsequent capacity to lead. The most recent example was in the United States of America, with presidential candidate Joe Biden stumbling during the 2020 campaign and suffering a hairline fracture of his ankle. The immediate media response was to ask questions about his age and health status in the context of his bid for the presidency. During the previous US presidential election in 2016, candidate Hillary Clinton had stumbled and fallen in the course of her campaign. The fall out in the media was an avalanche of stories discussing her fitness to lead the country.

In contrast to Biden and Clinton, Mamata Banerjee appears to lead a charmed existence. Not one political leader or media commentator has questioned her physical or mental capacity to cope with the injury and trauma. The absence of such questions could be an acknowledgement that the idea of physical vulnerability is alien to the media, especially in the context of Banerjee, whose usual style of walking fast during marches and rallies, striding across the stage when she speaks at election rallies, and so on, points to a level of physical fitness that is unusual, unfamiliar and, perhaps, a matter of discomfort for the media as well as the political opposition.