By Nasreen Habib

Contrary to popular perception, the North Eastern states of India are as patraiarchal as the rest of the country, says an editorial in the Assam Tribune. Figures show that fewer women candidates are fielded in elections in the seven states. And even fewer candidates wield actual power. This piece takes a deeper look into the recent assembly polls in Mizoram. This piece was first published in the Assam Tribune (1st December, 2018)

The sort of coverage the recent Assembly Elections in Mizoram received in the national media has been unprecedented. Some have commented that the Northeast is no longer the periphery it was thought to be, there is increasing interest in the politics and culture of the North Eastern states, unlike earlier where the focus shifted to the region only in the case of a bomb blast or ethnic violence. However, as soon as the elections are going to be over, the coverage of the North East too will wane, except when there is an unusual event such as the dethroning of Lenin’s statue in Tripura or, predictably, incidents of violence. So, if we look more closely, the narrative has stayed the same, one of conflict and violence. It is as if the region merits no long-term engagement or exploration into local issues, such as erosion in Assam (7.6 percent of Assam’s land has been eroded in the last 10 years). The elections in Mizoram have also brought out one factor that was relatively unknown, that the North East is as misogynist as the rest of India. In the last Assembly elections, in matrilineal Meghalaya, no woman MLA was inducted into the Cabinet, and in Nagaland, no woman MLA has been elected to the Assembly so far! In Mizoram, the statistics are only marginally better – four women have been elected to the State Legislative Assembly in its 46 years as a State.

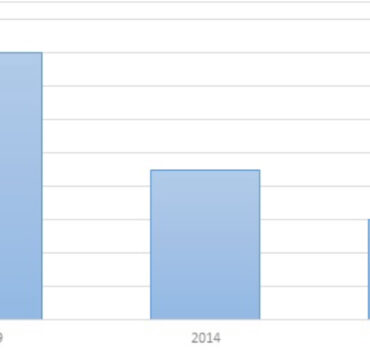

In the last Assembly elections in 2013, political parties had nominated only three women candidates. In the recent Assembly elections held on November 28, 2018, the number of women candidates has gone up to 15. However, if we mull over the fact that the only strong candidate who has a realistic chance at winning is Vanlalawmpuii Chawngthu, the only woman in the assembly who is also a minister, then the scenario is no less bleak than before. 200 candidates had filed for nominations, and only 15 of them are women. Mizoram is one of the states in the country where the representation of women in politics is among the lowest. Chawngthu is the first Mizo woman to be a minister in the State Government and she is also the general secretary of the Mizoram Pradesh Congress Committee. Again, though a powerful minister with a stronghold on regional politics, her father was a former minister who aided her growth in the party. The newly formed party, the Zoram People’s Movement (ZPM), has fielded two women candidates, both of whom come from political families. Zaichhawna Hlawndo, an evangelist who is the president of another formation, Zoram Thar, is fighting the Assembly elections in ‘the name of god’. His two daughters — Lalhrilzeli and Lalruatfeli — both educated in the UK, are contesting from two seats. Dynasty politics, like in the rest of the country, and indeed all over the world, has sunk its roots in Mizoram as well. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has fielded six women candidates but as the national party has minimal presence in Christian-dominated Mizoram, there are doubts if any of their candidates will make the cut. The only encouraging news is that the party has included two women in leardership roles — Zohmingliani as the vice president and Lalrinkimi as the secretary.

Zoramthanga, former CM and president of the Mizo National Font has clearly said: “If we had a strong woman candidate, we would have nominated her. But unfortunately our party does not have one. No woman contested on an MNF ticket in the 2013 Assembly polls either. Nor will there be a woman candidate this time.” It interesting to note that in a State where women are visible everywhere, from plying on the roads with two-wheelers, picking up children from school, running small businesses, to toiling on the fields and in offices, there are no ‘strong’ women found competent to contest. It is pertinent to mark that when the call for votes comes from politicians, there is no gender imbalance. They ask for votes from the masses, both men and women. In Mizoram, more than half of the electorate is made up of women, yet there is little representation of that in the Assembly. As a representative democracy, the elected representatives cannot represent the voices of men in overwhelming numbers.

What is the solution, then? For a start, all political parties, across the spectrum, need to acknowledge the need for inclusive politics and involve women in decision-making roles. Political parties must also address the elephant in the room – reservation for women — not only in the Parliament but also within political parties. There is 33 per cent reservation for women in Gaon Panchayats across the country, in Assam it goes up to 50 per cent, and though there are instances when a woman representative is only the executioner whereas the real power rests elsewhere, mostly with a husband, it has to be acknowledged that this is only the beginning. As more and more women enter the system through some form of preferential treatment initially, politics will be strengthened by the views and inputs from the other half of the population. At a time of sweeping global change and plummeting economies, we cannot afford to ignore women’s voices, which may bring in the revolution we are waiting for. The future, as they say, is female.