By Vanaja C

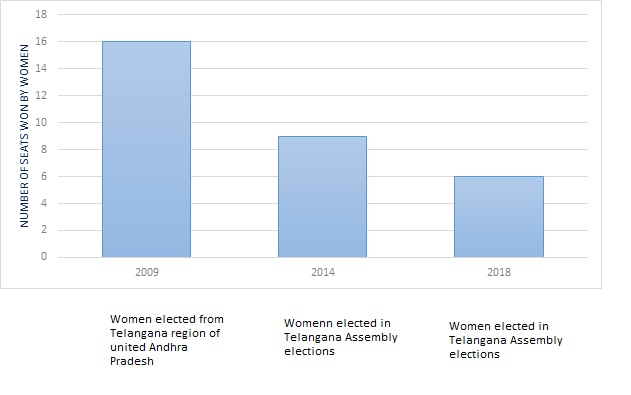

The recent Assembly elections in Telangana, the youngest state in India, with 119 Assembly seats, reduced the representation of women in the legislature to less than 5 percent, with only six of the 135 women who contested having won the elections. This amounts to just half the national average for women’s representation in legislative bodies (10 percent in Parliament and state Assemblies put together).

The result is in tune with a trend that began with the separate statehood movement. It is interesting to see how the movement for separate statehood and advocacy for women in politics have travelled side by side but on parallel tracks and how they have contributed or not contributed to each other. One cannot say the current outcome was created by design but it is worth noting that it came about so naturally.

Ever since the introduction of the Bill seeking to reserve 33 percent of all seats in Parliament and Legislative Assemblies in the Lok Sabha, there has been an active debate in the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh on the need to increase the presence of women in every sphere of politics. Although almost all political parties promptly announced that they were positive about the Constitution (108th Amendment) Bill, first introduced in Parliament by the United Front government of H.D. Deve Gowda in 1996 and commonly known as the Women’s Reservation Bill, none of them has walked the talk for over a decade.

The lame excuse was that it would be possible for more women to get elected only if everyone fields a woman in a particular constituency (which would be the case if the Bill, which mandates reserved constituencies for women, came into force). However, this logic was rightly questioned and the demand for a higher number of tickets to be allotted to women without necessarily waiting for legislation to mandate it has been made by every women’s organization in the state as well as many vocal women already in politics.

This finally resulted in a higher allotment of seats to women during the 2009 state Assembly elections. With almost every political party giving tickets to women, more than 200 female candidates were in the fray. Interestingly, not many women had to fight against each other in most constituencies, men were their primary opponents. Thirty six women won and, when the government was formed, six women were inducted into the cabinet.

This was the highest number of women in any cabinet since the creation of the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh state in 1956. For the first time a woman was put in charge of the Home Ministry, a prestigious and powerful portfolio that has been invariably held by a man. Women were also given other important portfolios, like mining. Again, this was the first time women had been entrusted with portfolios other than the customary welfare-related ones: women’s welfare, children’s welfare, social welfare, and so on. Of the 36 women elected during the 2009 polls, 16 were from the Telangana region; the female Home Minister was also from the same region.

Then came the bifurcation of the state and the 2014 elections. But before examining those election results, it would be worth looking into the parallel movements for more women in politics and separate statehood for Telangana. If the demand for women’s representation in politics began in the mid-1990s with the introduction of the Women’s Reservation Bill in Parliament, the demand for Telangana to be declared a separate state was also renewed (for the second time) around the same period, with some professors, school teachers’ organisations and students taking the initiative. While there was active engagement with the debate on both demands, the two discussions were always on parallel tracks, never together.

When the movement for a separate state intensified, and political parties were playing opportunistic politics, students of Osmania University took the lead, helping the movement spread and become strong. Students actually showed the way to organise effectively for the cause. All student organisations came together keeping their different political agendas aside and formed a Joint Action Committee (JAC) with the goal of achieving the creation of Telangana. This became a role model for organising in other spheres, too, even for political parties. A political JAC was formed under the chairmanship of Prof Kodandaram. Almost every wing of Telangana society also formed JACs: there was an employees’ JAC, a teachers’ JAC, a lawyers’ JAC, and so on. If there were 100 people in a sector there was a JAC.

It is important to note that all these JACs were dominated by men. Women were glaringly missing in all the JACs, except for some token representation in a few. There was a women’s JAC, which had drawn in women from many sectors, but it was unable to play any major role in the movement. The dialogue in civil society was dominated by the injustice suffered on account of being in a united state and the justice that can be achieved through bifurcation. Women could be seen in large numbers in the Telangana movement, especially in efforts to promote cultural traditions, like playing Batukamma (a festival of flowers revived during the movement) and participating in other age-old festivals, such as Bonalu. Kavitha, daughter of Telangana Rashtra Samithi leader K Chandrasekhara Rao (KCR), had launched Telangana Jagruthi, under which these symbols of cultural identity were revived with the help and participation of women. However, promoting the political empowerment of women was never on the agenda of the organisation.

The movement for separate statehood for Telangana was focused on seeking justice in three major areas: water, funds and employment. Accordingly, every debate was centred around the injustice meted out to the region in these areas. Gender was never identified as an issue even though statistics clearly showed that the status of women in Telangana was weak and that violence against women was much higher in the region than in the rest of Andhra Pradesh. It must be noted that a few women did consistently raise the question of whether the new state would promise a safer Telangana for women. The question was not answered then but some minor attempts to tackle gender-based violence were made after the formation of the state.

Returning to the 2014 Assembly elections, a total of 317 women stood for elections in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (the total number of contestants in the fray was 3910). Only nine women were elected in the first election to take place in the newly formed state of Telangana, seven less than in 2009. At the same time 18 women were elected in the residual Andhra Pradesh, just one less than before. It is important to note that the success rate of female candidates was higher than that of males: 8.52 (women), 7.41 (men).

Returning to the 2014 Assembly elections, a total of 317 women stood for elections in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (the total number of contestants in the fray was 3910). Only nine women were elected in the first election to take place in the newly formed state of Telangana, seven less than in 2009. At the same time 18 women were elected in the residual Andhra Pradesh, just one less than before. It is important to note that the success rate of female candidates was higher than that of males: 8.52 (women), 7.41 (men).

In the parallel general elections of 2014, while three women were elected to the Lok Sabha from the residual Andhra Pradesh, there was only one female Member of Parliament from Telengana: Kavitha, daughter of KCR, the TRS leader.

Interestingly, Dalit political empowerment was one of the election promises of the TRS. The party had even said they would make a Dalit the first Chief Minister of the state. Of course, this topic was never discussed after the elections and party head KCR went on to become the CM. It is important to note that there was not even lip service to women’s empowerment in general and women’s political empowerment in particular in the party’s agenda before or after the elections.

The most heartbreaking development was that the new state, which took charge from the united state that had six women ministers, did not give a single cabinet position to women. Women’s organisations cried foul but nobody cared. During the entire term of four and a half years (the recent Telangana elections were precipitated by the dissolution of the Assembly in September 2018, before its term ended), never was a woman inducted into the cabinet despite the fact that the cabinet was expanded a couple of times, not to mention that portfolios were shuffled and new male members were inducted. Even women’s welfare was handed over to a high profile male minister, along with Roads and Buildings; he obviously never recognised women’s welfare as his portfolio since he took no initiative or action on that front.

The new government did announce a committee for women’s safety with an IAS officer, Poonam Malakondayya, chairing it. She organised meetings and consultations over three months and produced an extensive report on what needed to be done. However, most of the committee’s recommendations were never followed up. Later, a joint initiative of women’s welfare and the police was launched with SHE teams meant to curb “eve teasing” in Hyderabad city but plans to extend it to the rest of the state are still pending. Another women-related initiative was the bifurcation of seats in city buses, with iron grills between men and women. Yet another initiative involved increasing the government’s cash gift to girls at the time of marriage – from Rs 50,000 to Rs one lakh. But, significantly, no special initiative was introduced to promote women’s education. Meanwhile, Telengana continues to pop up in every other survey/statistical report released by government and non-governmental agencies as one of the top places in the country that is unsafe for women in terms of both gender violence and gender-based discrimination.

By the time the 2018 Assembly elections came around, every political party had conveniently forgotten about their promise regarding reservations for and promotion of women in politics.

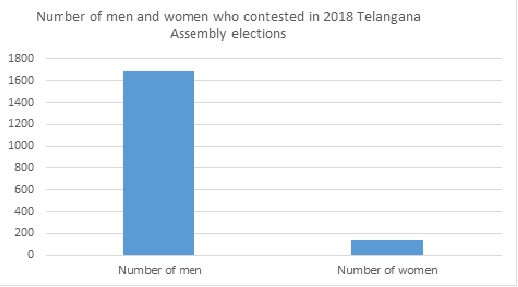

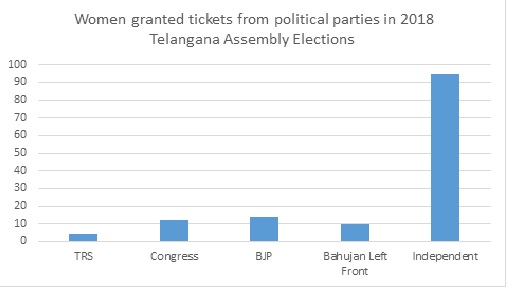

Women were allotted very few seats in the recent Assembly elections. The ruling TRS had given only four tickets (out of 119, which is less than four percent) to women; significantly, three of them won (which translates into a 75 percent success rate). The Congress-led political front had given 12 tickets to women, while the BJP issued 14 B forms to women and the Bahujan-Left Front fielded another 10 women, including a transgender person. One more woman contested from the BSP. This meant that political parties together put up only 41 candidates for 119 seats. However, a large number of women contested as independent candidates, put off by the attitudes of the political parties. So a total of 135 women stood for election, forming less than 10 percent of the total of 1,821 candidates in the fray. Women representing the Congress-led Front put up a tough fight and lost to their rivals with very slim margins. BJP candidates – both women and men – did not fare well. None of the women who stood as independent candidates won seats.

Another interesting but heartbreaking part of the recent elections in Telengana is that women voters outnumbered men in many constituencies even though the number of female voters was slightly less than the number of male voters across the entire state taken as a whole. Telangana has a very high number of female-headed families, with husbands having died in the process of migration or due to suicide (usually related to the crisis in farming) or alcoholism; or, of course, having left the family to seek other pleasures in life.

It is not known whether the higher turnout of registered women voters this year is related to the high proportion of female-headed families. But the fact is that as many as 55 of the 119 Assembly constituencies have higher numbers of female voters than male voters. The gap is particularly visible in a couple of constituencies. Despite this none of the political parties thought of fielding women at least in women-dominated constituencies. Needless to say, every political party had done careful calculations and given tickets taking into account the strength of the community – aka caste – in each Assembly constituency. None of the political decision-makers seem to have thought that women, who constitute 50 percent and sometimes more than 50 percent of the voters, were important enough to be considered a politically significant segment of society.

Having won the recent elections with a good majority, TRS has formed the second consecutive government in the state, with the promise of building Golden Telangana again. The swearing-in ceremony had the Chief Minister along with a Deputy Chief Minister taking oath. A week later, calculations are still on to accommodate all castes according to their relative strength while constituting the cabinet. The media are coming up with stories every day with their own calculations and guesstimates based on internal sources. No woman’s name has been heard yet. And no wonders are being expected in view of past experience. The question of whether the new state will be safe for women and promote the empowerment of women still remains a big question.