By Editors

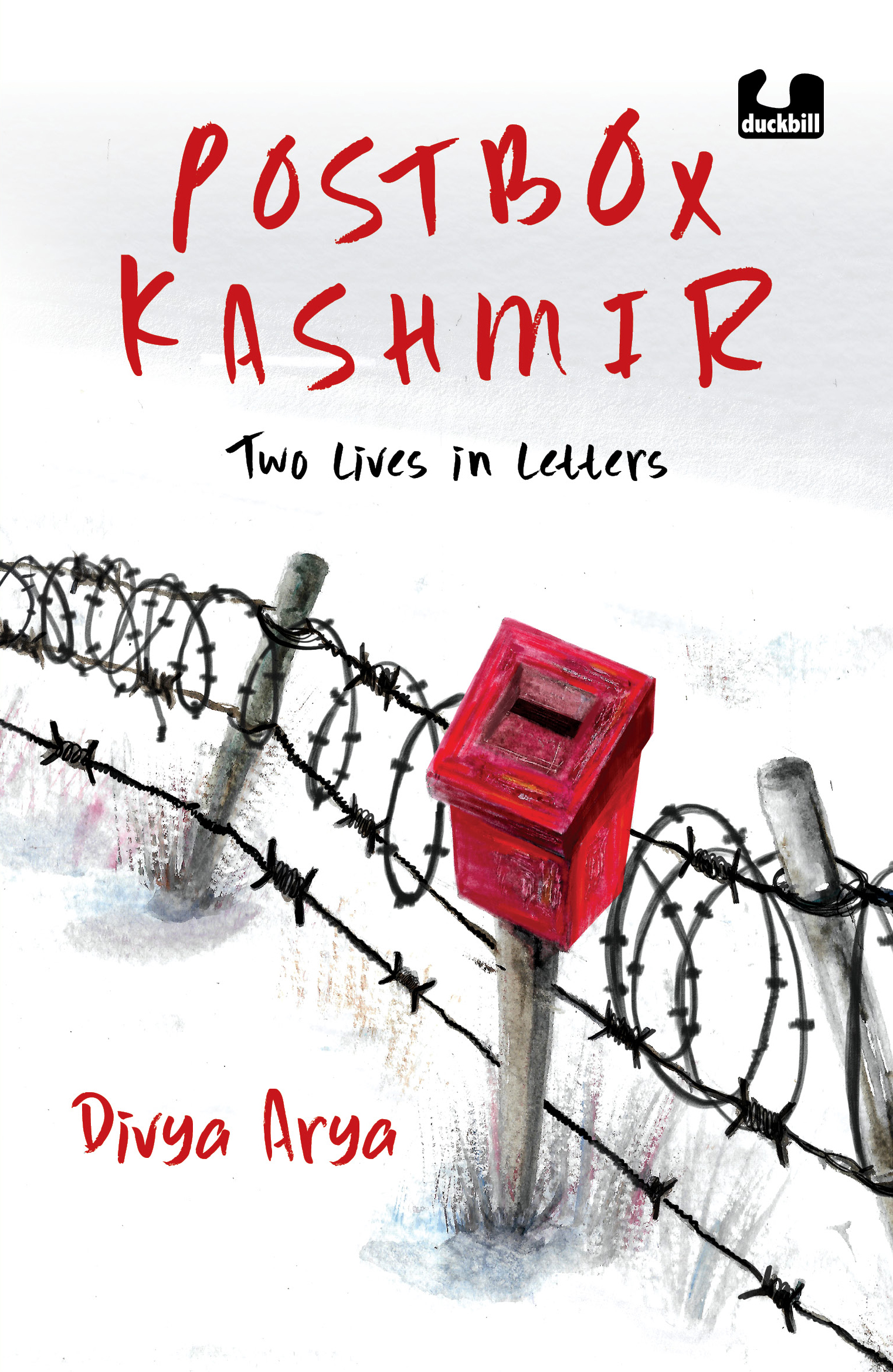

NWMI member Divya Arya has been telling people’s stories for almost two decades now. Navigating video, audio and text mediums across English and Hindi languages, Divya Arya explores human rights and social justice issues with a gender lens. An award-winning journalist, Divya is currently with the BBC. She is the first journalist from India to be chosen as a Knight Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan. Divya’s first book Postbox Kashmir: Two lives in letters is a work of non-fiction with a remarkable form. It is a collection of letters exchanged between two teenagers Duaa, growing up in Srinagar and Saumya, in Delhi. The book was released on August 5, 2021, to mark two years since the abrogation of Article 370 granting special status to Jammu and Kashmir.

Divya says, “Writing Postbox Kashmir: Two lives in letters, has had an almost therapeutic quality to it. An affirmation in the possibility of dialogue and empathy. The book of letters, as we fondly called it in the beginning, rests on the power of slow communication. They’re able to discuss the very mundane to the most contentious. Writing, waiting, listening to each other. As I charted the contentious political history of their present, what stayed with me was their ability to shoulder, yet not buckle under its weight. Instead, find faith and friendship.”

Read an excerpt from the book right here:

Saumya’s questions were innocent and honest. She wanted to understand.

I couldn’t understand one thing—why did the army attack those girls? Army is for our safety, right?

The Indian armed forces are a hallowed institution. They represent an idea beyond the individual. For the greater common good. Men and women, who choose to train to be physically and mentally tough enough to fight, kill or even die. Sacrifice their life for the nation. To defend its borders, its people.

Saumya had grown up watching an elaborate parade on 26 January, India’s Republic Day, every year. It was a winter morning ritual common across millions of homes in the country. Over rounds of tea and breakfast they watched the more than three-hour-long live broadcast that went through the same motions every year but never tired its viewers. In fact, the routine built a bond. When the President would unfurl the national flag, stand in salute, the national anthem would be played, and Saumya would leave her favourite spot on the sofa in front of the television in her house and jump into attention too, singing along till the end. A moment of patriotic fervour.

As columns upon columns of soldiers would march on, her chest swelled up in pride. And eyes welled up when she heard the battle accounts of the bravehearts being honoured with the likes of Shaurya (courage), Vir (brave), Kirti (glory) Chakras, the titles underscoring their heroism. Sometimes these were accepted posthumously by their wives, sisters, mothers. Who stood stoically, as they awaited their turn, fighting a million memories tearing their heavy heart.

…

There was another factor that influenced Saumya’s relationship with the Indian army. Her parents used to work at a petrol pump, whose owner was a war widow. Her husband had been martyred during the Kargil stand-off in Kashmir in 1999, when India and Pakistan came head-to-head in a warlike situation. On 26 July 1999, the Indian army successfully recaptured all the posts that had been occupied by Pakistan’s army. Since then that day was marked every year as Kargil Diwas (Kargil Day) to remember Indian soldiers’ sacrifices. Saumya grew up witnessing the annual commemoration on Kargil Diwas and said it instilled a sense of pride in her young mind. She felt attached to the Indian army. Knowing the family of an army man made their sacrifices for the country feel very close and real.

Saumya’s references clashed with the picture that Duaa’s letter evoked. And it wasn’t just the letter, as she engaged more with Kashmir, she could not escape the reports of pellet gun injuries, pictures of bloodied protestors of her own age that filled the newspapers and TV bulletins those nights, telling the story of the fight with the ‘internal’ challenge. When the army was engaging with its country’s own citizens and not an external enemy across the border.

Duaa had clarified in her letter that in the particular clash with the girls’ football coach that Saumya referred to, it was the police and not the army that was involved. The state police is a force made up of locals while the army is made up of soldiers from all over the country. And the army has been deeply involved in Kashmir. Not just in defending the borders of the state (and the country) with Pakistan and China in times of war but also as a force for maintaining internal peace and security. The army is assisted by the two paramilitary forces, the Border Security Force (BSF) and the CRPF. They have been inside Kashmir for more than three decades now. Hundreds of thousands of jawans are stationed across the state. It is an unusual sight for anyone who has not lived there. But for Duaa, who grew up witnessing that constant presence in Srinagar, it felt usual. She told me that she had gotten used to seeing them, that it did not matter and that she had learnt to ignore it.

They stood, with their rifles facing down. Inside the big cities, towns, villages. In their marketplaces, in neighbourhoods, on the roadside. Many times in bunkers, so omnipresent that they have become landmarks. Often cited by residents while giving directions, just as one would mention a traffic light or a shop. That’s how numerous they were when they started getting built in the 1990s. There are no official figures of how many were built, but estimates suggest they were in hundreds. They were a symbol of the state when the government was struggling in the face of an armed rebellion. Over the past decade or so, several bunkers were removed from Kashmir to reduce the visible security presence there But in many mohallas, their memory lingers.

…

History gives perspective. For generations like those of Duaa—born after the insurgent 1990s, after militancy had been brought under control, after daily violence had ebbed, but while the presence of the forces persists, and a new rebellion rears its head at the horizon stirring alive latent fears—it brings a conundrum: should one inform one’s life and opinions by what they are witnessing in the present or by what has been recorded in words, songs and memories of the past? To look ahead to the future or look back at the history.

And in Kashmir, it is still not easy to reveal where you are looking. Feigned ignorance or a refusal to take a strong position is often a safe place. Not denying the past or one’s personal experience of it, but refusing to publicly acknowledge its lasting influence.

To enable dreaming of a safe future. It’s a silent and difficult choice.

—

Postbox Kashmir: Two Lives in Letters, (Penguin, 2021) is available here and in bookshops.

Related

Two Years of Suppressed Stories

Reflective lens: The aftermath of August 5, 2019, in Kashmir