By Shikha Mukerjee

Following the examples set by their elders and betters, would-be Romeos on the streets of Kolkata have begun harassing women with catcalls that mimic Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent routine of calling out to Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee using a particular tone: “Arrey, Didiiii O Didiiiiiiii.” When additions like “Didi ko kyon gussa ata hai?” are linked to the call, it is a perfect recipe for sexual harassers on the street to follow.

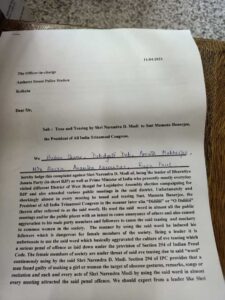

Election time is traditionally a free for all, but some boundaries cannot or, at least, should not, be crossed. According to a First Information Report (FIR) lodged at the Amherst Street Police Station in Central Kolkata on April 11, 2021, by Baban Shome, Debdyuti Deb, Amrita Mukherjee, Mita Hazra, Anamika Karmakar and Rupa Paul, the “said word” was used in almost every public meeting by the Prime Minister, “with an intent to cause annoyance of others and also caused aggravation to his male party members and followers to cause the said teasing and mockery to common women in society. “ The complainants are young women associated with the Bengal Citizens Forum, which held a demonstration outside the Amherst Street police station on Monday and vowed to raise the matter with the Election Commission. According to the complainants, “Being a leader, it is unfortunate to use the said word which basically aggravated the culture of eve teasing.” They pointed out that this was a penal offence under IPC Section 294.

By reporting the FIR, Bengali media have finally caught up with the story that has been playing out on television and in print for a week and, of course, circulating on social media. The fact is, however, that the media did not independently work on this story, even though three women leaders of the Trinamool Congress party, Minister for Women and Child Development Sashi Panja, Chairperson of the State Commission for Protection of Child Rights Ananya Chakraborti, and actor and candidate in the ongoing election June Malia had held a press conference to flag the issue. As Dr Panja said, “The way Modi has been calling out Banerjee’s name qualifies as ‘taunt kata or ‘titkiri mara’.” The Bengali expressions she used refer to men making lewd comments about women. Pointing out that “this was misogynistic and worrying,” she said, “That the Chief Minister of a state was being humiliated in this way is a matter of grave concern.”

The police complaint about the growing prevalence of sexual harassment in public areas mimicking the Prime Minister underlines the fact that this is a matter of grave concern, as pointed out by Dr Panja. Failure to maintain due decorum while campaigning and indulging in what the women who lodged the FIR believe is a penal offence effectively encourages others to follow the example set by a leading political leader like Narendra Modi.

Reports in the local and national media on the initial “Didi-O-Didi” dig did not focus on the fact that it amounted to catcalling. On the contrary, the media discussed it as Modi’s response to Mamata Banerjee’s earthy attacks on him and the Union Home Minister. National television channels resorted to the vox pop option, with journalists seeking out female voters during the third phase of the eight-phase election and asking for their reaction to the “Didi O Didi” jibe. Since women voters in rural areas did not express outrage and, according to journalists, seemed to have endorsed or been entertained by the expression, it was evidently assumed that women in West Bengal approved of the Prime Minister’s behaviour.

The media appear to have deliberately chosen to avoid the issue of deep-rooted misogyny reflected in what was essentially a catcall. By concluding that women voters did not seem to object, they also avoided confronting the reality of how women are socialised under patriarchy, trained to remain within the norms prescribed by the patriarchal order and made only too aware of the cost of rebelling against it. Under the circumstances it is hardly surprising that they would hesitate to call out catcalling by a powerful male authority figure like the Prime Minister.

By avoiding confronting the ugliness and violence of misogyny, the power of patriarchy over women’s lives, and the ways in which the patriarchal pact consistently humiliates women and violates their dignity, while reporting on the mocking words and tone used repeatedly during the ongoing political campaign, the media have undone all the pain, battles and scars that preceded the point at which a woman’s body and her dignity became a national issue, after the gang rape and murder of “Nirbhaya” in 2012. The news media, particularly television, seem to have also retreated from the point they had reached when they reported the verdict in the MJ Akbar vs. Priya Ramani case relating to sexual harassment in the workplace in February 2021. Not only was the judgment reported as breaking news, it became the lead story for prime time TV debates, and considerable coverage was given to the court’s opinion that “the woman has a right to put her grievance at any platform of her choice and even after decades.”

While the verdict and the terms on which the judicial opinion was framed have been criticised by some, the fact that the media reacted by giving the case and the verdict top billing was a giant step forward. By highlighting the problem of sexual harassment in the workplace and the fact that women found it difficult to report such violations, the media positioned itself as a not-so-timid champion of women’s rights and dignity.

In contrast, media coverage of women in politics and the brutal verbal attacks on them, their bodies and their conduct has been unacceptably non-committal, if not biased. This trend has been evident throughout the current electoral campaign, beginning with the wide and uncritical coverage given to the comment about Mamata Banerjee’s injury by Dilip Ghosh, president of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in West Bengal, at a public meeting on March 24: “Plaster has been cut, there is now a crepe bandage, and [she] keeps raising her leg and showing everyone.” He later went on to add: “If [she] has to keep her leg out, then why wear a sari, [she] could wear a pair of Bermudas instead so that [it] can be seen clearly.”

Mayawati, former Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh (UP), was viciously attacked as a “character worse than a prostitute” by Daya Shankar Singh, a vice president of the BJP in UP, in 2016, in the context of his allegation that she had sold nominations in the run-up to the elections. Fortunately, former Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley apologised to Mayawati for the unpardonable slur on her as a woman. It is also noteworthy that Singh was subsequently removed from his post by the BJP.

However, between 2016 and 2021, the party seems to have acquired absolute immunity from the consequences of abusing women online and offline. There have reportedly been incidents of women journalists being groped at BJP rallies in the course of the ongoing election in the state.

Instead of connecting all the violations – physical and verbal – as part of a pattern of harassment and violence against women, the media seem to have chosen to overlook such instances and thereby prove itself unwilling to challenge such conduct by anyone and to do its duty, which is to speak truth to power. Women’s rights to equality and justice seem to have been ignored, if not rejected altogether, by the media when it comes to women in politics. The fear is that once the media concede ground and buckle under the pressure of patriarchal and political power to reflect and perpetuate such vicious attacks on women in politics, the gains achieved through the long struggles that preceded this particular moment will have been voluntarily surrendered.