By Geetika Mantri

Suicide is the fourth leading cause for deaths of young people between 15 to 19-year-olds worldwide. This is an often-reported statistic. It is also alarmingly common to read about suicides in daily news with little to no context around it, even though it is closely linked to mental health. And the result of media reporting on suicides as standalone incidents, not adequately linked to socio-economic conditions and mental health of the victims is that it ends up being seen as an act of escape, a sign of weakness, or as the only resort for people in similar situations.

The stark example of this was the media debacle that followed the death of Bollywood actor Sushant Singh Rajput last year. He was found dead in his apartment in Bandra, Mumbai, and immediately, a section of the media attempted to dissect and analyse his life, his ‘last’ photos, videos, and conversations, to ascertain if he “looked” happy. There were also speculations about his ‘diagnosis’ – was he depressed? Did he have bipolar disorder? The terms were thrown around casually, as though somehow by doing so, news anchors and channels could, explain away his death, and possible suicide. It didn’t matter that they were not mental health professionals, and had neither the right nor the expertise to do so.

Not only was this a setback for mental health reporting but the coverage was also significantly triggering for many others, including journalists. When I reported on the mental health cost that journalists bore through 2020, overworked, depleted, reporting on the pandemic, the heartbreaking migrant crisis, the collapsing healthcare system and subsequent deaths, all while navigating concerns and fears around their own safety and health and that of their loved ones, the Sushant Singh Rajput saga did not help. The whole debacle soon turned into a witch hunt against Rhea Chakraborty, actor and Sushant’s girlfriend before he died, and the ensuing drug racket, the problematic nature of it deserves a whole other article.

Suicide Stereotypes

The coverage propagated the harmful stereotype that you have to look your mental illness – you cannot be depressed if you are seen laughing, you cannot be anxious when you seem calm, and you cannot be suicidal if your life appears to be going well, according to others. This is not only far from the reality, but also reinforces the same notions that contribute to erasure and denial of mental health issues and add to the stigma around it. Irresponsible reporting on suicides – especially ones where the method of suicide, place etc. are widely circulated and suicide is glamourized, such as by showing the victim as a martyr – also increases the risk of copycat suicides. Celebrity suicides especially have been known to trigger imitative suicides.

More recently, in mid-September, three students took their lives as they were afraid of failing the medical entrance exam, NEET (National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test). The deaths happened in a span of five days. These are not the first NEET related student suicides in Tamil Nadu – there are similar stories across the state. Student suicides themselves, linked to exam pressures are commonplace in India. However, the discourse on suicides often fails to acknowledge the systemic pressures, discrimination and challenges which create situations for bad mental health.

For instance, all of the three students who died in September – Soudharya, Kanimozhi and Dhanush – belonged to disadvantaged communities. Research shows that incidence of mental health issues like depression and anxiety is high among communities and groups have faced historical and systemic oppression and discrimination, such as LGBTQIA+ people, and racial and ethnic minorities.

Therefore, mental health, and suicide needs to be seen not just from an individual health perspective, but as a public health issue, to be addressed with a multidisciplinary approach that looks at socio-economic factors that are making people from certain backgrounds more vulnerable to mental health issues as compared to others.

And this is where the media can play an important role.

How to do it better

We have already seen – such as with the Sushant Singh Rajput example – how irresponsible reportage on suicide and mental health can be detrimental, undoing years of painstaking work to make the discourse marginally more sensitive. However, when the media covers mental health responsibly, breaking down what appears complex, it normalises seeking help, busts myths and harmful stereotypes, and makes these conversations more accessible. And the key to that is not only to do stories on mental health issues, but to bring that perspective to other stories too.

For example, when we talk about farmer suicides, we could look at the intersection of economic deprivation, debt and mental health. This does not necessarily need to look like searching for ‘symptoms’ of a mental illness while putting together the piece of a victim’s story, but merely enquiring about and including aspects of a person’s emotional distress into the story. By doing so, we shift the discourse from saying “mental health depends on one’s individual emotional strength” alone to also questioning the systemic mechanisms (or lack thereof) that lead to people being in such situations, and potentially taking drastic steps.

Mental health interventions can also take the shape of alleviating social and economic deprivation and enabling equal opportunities. As journalists, we must approach suicides and mental health with an evolving and intersectional understanding – not only to add value to our stories, but also for public good, which remains one of the tenets of impactful journalism.

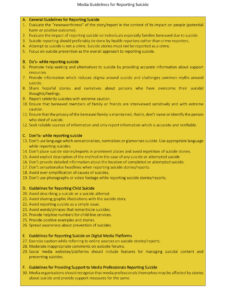

This resource was prepared by SPIRIT after compiling media guidelines developed by the World Health Organisation, Canadian Psychiatric Association, Hunter Institute of Mental Health, The Carter Centre, Samaritans, SNEHA-Suicide Prevention Centre (Chennai) and National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (India).

You can use this resource for more information on reporting suicides.

Geetika Mantri is Senior Editor of The News Minute and member, Network of Women in Media, India. She won the Project SIREN Award for sensitive reportage on suicides, announced by the Centre for Mental Health and Policy at ILS, Pune, in September 2021.