By Sowmya Rajendran

In October 2017, US based law student Raya Sarkar put together a list of alleged sexual harassers in the Indian academia. At the time, there were several discussions in the media about how to approach ‘The List’ or LoSHA (List of Sexual Harassers in Academia) as it came to be called. Would it be ethical to report on a list which just had names without specific allegations? Especially when the names of those who made the accusations remained anonymous?

Feminists, too, were divided on the list, with one section insisting on due process and others pointing out that survivors were re-victimised by due process. Eventually, several media houses did report on LoSHA though many of the larger, mainstream ones chose to ignore it.

But in 2018, all that changed. The men who faced accusations this time around were more in the public eye, some of them from the media fraternity itself. More women were willing to come forward and name their sexual harassers, giving details of the incident (s). This led to some of those men being forced to resign from their jobs – including Minister of State MJ Akbar – or at least face an internal investigation in their place of work. The story exploded in the entertainment industry, with men like Nana Patekar, Alok Nath and Vairamuthu facing serious allegations of sexual harassment and assault.

This time around, nobody could turn a blind eye to what was happening. Though the media reporting on the ‘Me Too’ movement was far more sensitive than what it was, say, a decade earlier (Tanushree Dutta’s allegation about Nana Patekar at the time was reported as a “tantrum”), there was scope for improvement – in what sort of questions were asked and of whom, and how the story itself was presented.

Notably, Priya Ramani, first broke her silence by publishing an article on Vogue about her harrowing experience of sexual harassment at the workplace. While she did not name her perpetrator then, she did so later, prompting MJ Akbar to file a defamation case against her. That the Delhi court not only dismissed the charges against her but also observed that a woman has the right to speak up against sexual violence and should not be silenced, is a shot in the arm for survivors and journalists who are committed to gender justice. She was acquitted by a Delhi court in the defamation case filed against her by former Minister MJ Akbar. Though MJ Akbar has now moved the Delhi High Court appealing against the acquittal, the verdict in the case has already made quite an impact on the #MeToo movement in India.

The NWMI is committed to working towards ensuring that media coverage of violence against women is more sensitive and nuanced, enabling victims and survivors to get justice in an environment where women feel safe and can exercise their right to equal citizenship.

We recognise that media coverage is often a double-edged sword. On the positive side, it increases public awareness about such crimes and puts pressure on the authorities to take action. On the negative side, incessant coverage of certain cases, particularly sensationalised cases of sexual violence, can obscure the widespread prevalence of many different forms of daily violence against women all over the country. Unless it is balanced and sensitively handled, such coverage can also be voyeuristic and titillating; it can increase the sense of vulnerability and insecurity among girls and women (including survivors of such violence), and lead to restrictions on their freedom and rights.

In addition, some of the media coverage in the immediate aftermath of the gang-rape in Delhi provoked and amplified strident calls for harsher punishments for such crimes – capital punishment, chemical castration, and so on – despite the fact that most women’s groups with long experience in dealing with gender violence have consistently cautioned against such kneejerk reactions that could worsen the situation.

We recall the thousands of girls and women all over the country who have been physically, sexually, psychologically abused and injured or killed. As journalists we urge the media to pay due attention to sexual violence perpetrated on Dalits and Adivasis, as well as women in militarised zones, where security forces are granted impunity by law.

Read our full statement on this here.

Here’s a list of Dos and Don’ts on reporting on ‘Me Too’, or any sexual crime for that matter:

Do: If you are interviewing a survivor, make them comfortable first. Tell them that you believe their story and that you will respect their space and decisions to share or not share certain details. This doesn’t mean that you don’t follow journalistic rigour in getting the facts of your story together.

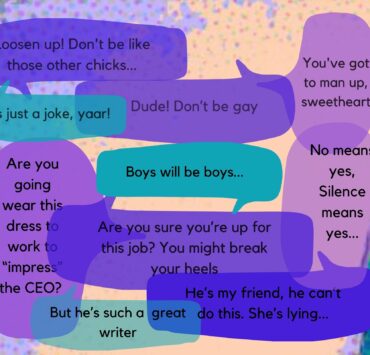

Don’t: Don’t adopt a judgmental or doubting tone when asking questions. Always remember that sexual harassment is NEVER the fault of the survivor. It doesn’t matter what she was wearing, where she was going, or what she was eating/drinking. If you are yet to get out of this mindset, please don’t do stories on sexual violence. You’re not ready yet.

Do: Inform the survivor of what may happen once the story is out. They may not be aware of the possibility of a defamation case or the barrage of media attention that can come their way. Even if the person chooses to be anonymous and the accused decides to go to court, the court may insist that the media house reveal the name. India does not have a blanket law that protects journalists from revealing their sources.

Don’t: Don’t lead the survivor on with false claims and assurances that you know you cannot keep. Doing so is deceitful and can potentially traumatise the survivor even more. It can also lead to considerable legal expenses for them.

Do: Those accused of sexual harassment can go to court and ask for an article to be taken down or a media gag may also be imposed on reporting about a case. If your media house receives such a notice and it becomes necessary to remove or drop a story, keep the survivor informed.

Don’t: Don’t leave the survivor hanging, wondering about when the story will come out or when you will call them next. They need to know what happened and why.

Do: Allow the survivor to speak freely. Some may find it easier to just tell their version of what happened; some may be more comfortable with a set of questions. Avoid interrupting the person when they are speaking. These experiences can be triggering and it’s difficult for survivors to recount everything as it is. Adapt as you go along.

Don’t: While it is okay to ask questions if you need some information clarified, don’t insist on details if the person is unable to be specific. Many people block out traumatic incidents from their mind because that’s how human psychology works. Their inability to recall something doesn’t mean they are lying.

Do: Speak to the person at a time and place convenient to them. If you’re doing the interview over phone, always message first and ask if they can take the call then. We’re asking them to recall some very unpleasant moments from their life and they may not be mentally prepared to speak about the incident just then.

Don’t: We all have deadlines but that isn’t the survivor’s problem. If they are unable to accommodate your request or need more time to decide if they want to speak at all, don’t try and guilt-trip them about your work pressures. They owe you nothing.

Do: It helps to have supporting evidence when you publish a ‘Me Too’ story. Ask for contacts of people who may be able to confirm the survivor’s account or any documentary evidence like emails or texts. However, always explain why you’re asking for this and make it clear that this is not because you don’t believe them.

Don’t: Don’t share any such evidence you get from the survivor with anyone unless the person has expressly given you their consent to do so. Sometimes, the survivor might ask you to block out a certain detail while publishing the story because they are not comfortable with it being in the public domain. Respect their request.

Do: If the survivor wants to be anonymous and you’ve promised to keep them anonymous, please do so – and this is not just in the story, but also in your office and media networks. Only the people who absolutely need to know should know.

Don’t: Don’t share contact details of the survivor with anyone unless she gives you permission to do so. When a ‘Me Too’ story breaks, you may have reporters from other media houses asking you for the contact. Always check with the survivor before sharing the contact details – this is their story to tell.

Do: Share the quotes with the survivor before the story is finalised. She may have told you certain things while recounting the experience but may have later had second thoughts about it. Tell the person that such an option to review their quotes is available.

Don’t: Don’t pressure the survivor to respond as soon as you’ve sent the quotes. They are not required to run their life according to your schedule. Allow for sufficient time for them to get back. Include it politely in the email or message that you send.

Do: Present your story with sensitivity. As a journalist, you must be careful when you report on sexual harassment where the accusation is yet to be proved. However, for far too long, the onus of proof has been on the survivor, while no questions are asked of the accused. Understand what’s at stake here for the survivor and present the story with empathy.

Don’t: A sensational headline will grab eyeballs but don’t do stories on sexual violence if your commitment doesn’t run deeper. It’s important to get the story noticed, but NEVER at the cost of lowering the dignity of the survivor. Don’t turn a person’s trust in you into a voyeuristic exercise. Fight with the editors if need be.

Do: If the story is not strong enough or if you feel the survivor may be harmed in any way and nobody is going to benefit from this journalistic effort, drop it. The effort you have spent on it doesn’t matter in the larger picture. However, inform the survivor that the story has been dropped and explain why.

Don’t: Don’t leave the survivor hanging by not telling them that the story has been shelved. They have invested a lot in telling you their story and they deserve to know.