By Editors

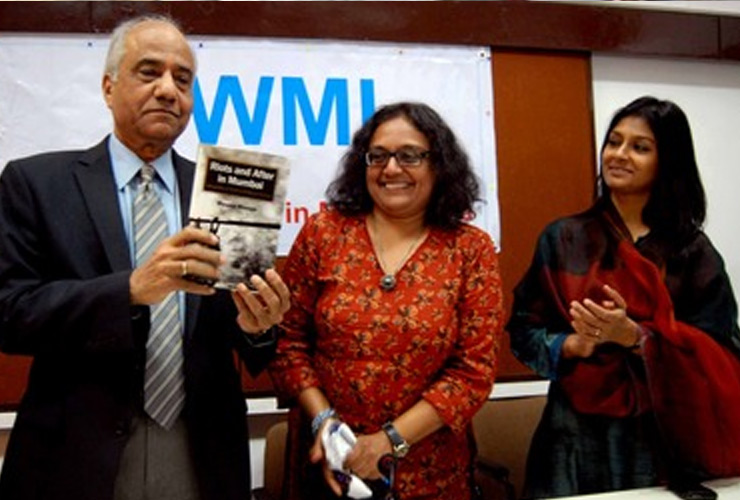

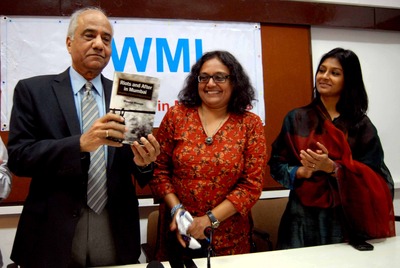

In Riots and After in Mumbai: Chronicles of Truth and Reconciliations (Sage Publications, 2012), Meena Menon (deputy bureau chief and deputy editor, The Hindu, Mumbai) intersperses her observations as a reporter on the 1993 communal riots with narratives of loss, pain and despair. The book was released by Justice BN Srikrishna at a meeting in Mumbai on March 1, 2012. The event, co-organised by NWMI Mumbai, and held at the Mumbai Press Club, also featured actor Nandita Das, who directed the film Firaq on the Gujarat violence, and social activist Firoze Ashraf.

Justice Srikrishna put the onus of the 1992-93 riots on the state machinery. The judge, who headed the one-man commission of inquiry into the 1992-93 riots and whose recommendations were never implemented, declared, “No riot can continue for 15 days in one phase and yet another 15 days in the second phase without the state being in cahoots (with the perpetrators).”

What did the Srikrishna report achieve? Was it a waste of time? Though his “report was rubbished” and he himself was labelled “an anti-Hindu”, Justice Srikrishna, a former Supreme Court judge, maintained that the work of his inquiry commission was “an essential process that provided a catharsis of sorts. The public needed to know what had happened.” He pointed out that documentation of an event of this magnitude, through work such as Menon’s book, is of great importance for we learn only from our mistakes. “Those who forget history are doomed to repeat it.”

In her introductory address, senior journalist Kalpana Sharma noted that the book’s perspective was enriched because it was authored by someone who had witnessed the riots from close quarters as a reporter and had then gone on to document the aftermath. She said the book was a record of an important time in Mumbai’s history and that it framed the Mumbai riots of 1992-93 in a particular historical context.

Menon, who had started the book as a project for a fellowship, said that through her research and interviews for the book she simply wanted to go back and see how the riot-affected people had coped with their lives after the violence.

Nandita Das said it was this aspect of the aftermath or what lingers on after an act of brutal heinous violence – be it anger, fear, guilt, revenge, prejudice – that intrigued her the most and formed the nub of her ensemble film. Social activist Firoz Ashraf, who suffered during the 1992-93 Bombay riots and who also features in the book, pointed out that the riots destroyed not just life and property but also the city’s multicultural character.

In the discussion that followed, lawyer Yusuf Muchala, who has been arguing many cases on behalf of riot victims, pointed to serious lacunae in the law and called for the passage of the anti-communal violence bill. Justice Srikrishna reiterated that an inquiry commission is not meant to deliver justice; the purpose is to expose what happened. It is the job of the state machinery to bring it before the judge. NWM member Jyoti Punwani, who has written extensively on the riots, commented that if the cause for justice is forgotten it is because the media and civil society have allowed that to happen. The pressure on the state government to bring the guilty to justice must continue. On a more hopeful note, anti-communalism activist Javed Anand concluded that it was persistence that had enabled 31 of the accused in the Sardarpura massacre case, post-Godhra riots of Gujarat, to be convicted. We need such persistence in the quest for justice in the case of the Mumbai riots.