By Zoë Liz Philip

(Guest post)

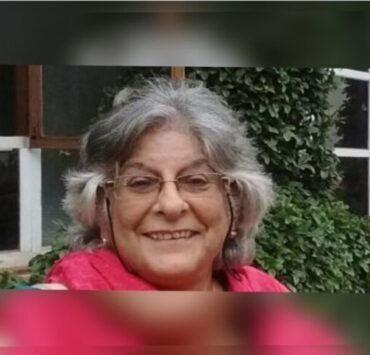

Ragamalika Karthikeyan (He/She) is the Senior Lead for Audience Revenue and Special Projects at The News Minute, an organisation that focuses on reporting the stories from south India. This NWMI member’s latest project is Inqlusive Newsrooms, an initiative to train journalists and editors across the country in using the correct language while covering queer stories. The project is led by The News Minute, Queer Chennai Chronicles, and queerbeat and supported by Google News Initiative. In this interview with NWMI, she talks about the significance of this project, in both her career and the field of journalism at large.

NWMI: While launching Inqlusive Newsrooms, you said that this project was about maintaining a “person’s personhood”. What does this mean in the context of reporting LGBTQIA+ stories?

Ragamalika: When it comes to reporting on LGBTQIA+ communities, the model that most organizations and journalists have used is, they decide when they’re going to cover a story depending on whether there’s either been a pride march or a murder or violence in some way or another. When this happens, you are automatically looking at queer people as items of curiosity and you’ve reduced a person to either an object or a victim.

Then, the language that is used around them also becomes very reductive. For instance, one term used very frequently in the media is “transgenders”; transgender is a term that is to be used as an adjective, not a noun. You do not call a group of tall people ‘talls’ or a group of short people ‘shorts’. When you do that to transgender persons, it becomes extremely dehumanizing. That kind of language comes in when newsrooms don’t have an understanding of the lives of queer persons and aren’t following the conversations that are happening inside these communities or even what these communities are telling the media.

A lot of stories about trans people start off along the lines of, “This person was born as a man and then became a woman.” Again, it’s about catering to the voyeuristic curiosity of the reader and, to some extent, of the journalist as well.

That is not the right way to talk about people, or the right way to talk about a person’s identity. You don’t necessarily say that about any other community.

If we’re out on the streets and marching, you’re not talking about our rights, you’re not talking about why that march is happening. When there is a murder, it boils down to the course of events that started when the queer person ran away from their families or how their identity angered the families enough to murder them. Even in these reports, you’re deadnaming people, denying them their dignity in death. (‘Deadname’ refers to the name a trans person has left behind when they transition, usually the name given to them at birth by their families.)There’s no dignity given to our chosen families in news reporting — reporters go back to the biological family to ask questions. For the families, LGBTQIA+ identities are a matter of shame, which is what the reporters will write down verbatim. But who is this person? Who is their chosen family? Those are things that nobody actually looks at. If you plan to represent this person, are you representing them as a human being, or are you just representing them as an item of curiosity? This is the basic problem with the way reporting is done.

What are the kinds of stories that queer people want the media to tell?

As with any marginalised group in society, there is a lot to cover. Issues affecting a community can be employment, housing, discrimination, access — access to healthcare, access to political spaces, access to education. In different communities, marginalisation works differently, and therefore, how it affects communities is also different.

The LGBTQIA+ ‘community’ is not a monolith. It is made up of various castes, classes, religions, and people of different abilities. Once you realise that you cannot club us under one umbrella, you start looking at what the different issues affecting different people are. How does an out-queer person who does not express their gender in a heteronormative way find housing? A lot of queer people are disowned by their families, and have had to flee their homes – how are they even going to have access to basic documents to access housing, or education, or employment? All of these are bigger issues that we should be talking about, but we rarely do.

What is your aim with Inqlusive newsrooms? What kind of training do you want to give journalists?

The way we decided to go about it is to start by defining the fundamental problems, and one of the problems we’ve identified is a lack of knowledge. There just isn’t enough education. But there are enough journalists who do know. As a journalist myself, I know from my experience that the community often points out mistakes when they’ve been made and that there are people who are willing to change. It’s not always the case that somebody actually wants to be discriminatory. Not all, at least. Yes, some people are bigoted across society. But the larger problem that journalists seem to voice most often is, “We don’t know. Only if you let us know, can we act.” We’re responding to that call by saying, “We’ll tell you how to do it.” We will tell you what the problems are and how to address us correctly.

That is why we are coming out with a media reference guide. The media reference guide will have a glossary. It will be available in English and five other languages: Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Hindi, and Marathi. We want to make the guide as exhaustive as possible. There will be a list of basic things that journalists look at and things that editors/commissioning editors have to look at before reporting a story on LGBTQIA+ communities or individuals.

There is, of course, a lot of conversation about appropriation. Who is supposed to report a particular story? Is it okay for a cisgender, heterosexual person to write an opinion piece about queer lives? These questions will also be answered in the guide.

We are looking at every beat that journalists would usually look at. For example, If any journalist wanted to do a political story involving LGBTQIA+ persons, they could refer to the politics section of the guide before they started writing it. The idea is to make it as easy as possible for people to do the right thing when they want to do the right thing. We want to distribute the guide freely, across the country to newsrooms and journalists who are interested and to whoever we can reach out to.

Once the guide is available, we will start conducting trainings. It is more helpful when someone is sitting in a classroom set-up and discussing these things. It makes room for human input. The plan is to do seven training sessions this year across the country. Three of these will be in English, two in Tamil, and two in Hindi. This is to make sure we are not just looking at English-language journalists, but reaching out to all journalists across the country.

Inqlusive Newsrooms has also announced fellowships for journalists. What is the vision for these fellowships?

Inqlusive Newsrooms is awarding fellowships to journalists to do stories that need to be deeply reported because, a lot of the time, there aren’t a lot of opportunities to write about LGBTQIA+ lives. When newsrooms are not willing to pick up these stories, we’re saying, “Okay, we’ll provide you with the resources and the mentorship, go ahead and cover these stories.”

We are hoping that with all of this, there will be enough material in the media ecosystem of the country for us to be able to say, “Now you can no longer say that you don’t know what the right way to do things is.” We are providing an opportunity for everyone to do it the right way. That is our aim.

Coming to a place where you could launch Inqlusive Newsrooms, please walk us through the process of setting up something like this.

The honest answer is, this was something that a bunch of us who have come together from our own locations have wanted to do for a long time. As a queer journalist, I came out quite late in life, at least later than a lot of young people. But as a journalist, I have been covering LGBTQIA+ issues since the beginning of my career. Since then, it’s been activists, people in the communities, who have always guided me whenever I made a mistake. That’s how I learnt.

A couple of years ago, Queer Chennai Chronicles was having their litfest (on Twitter Spaces due to the pandemic). A panel that I was on along with Ranjitha Gunasekaran (Resident Editor at The New Indian Express) was a discussion on what kind of language we use in newsrooms when it comes to LGBTQIA+ stories, and we discussed the need for style guides to help with this.

Meanwhile, the Madras High Court had at this time suo motu taken up a list of issues and was issuing directives to different government departments and bodies about using the right language for LGBTQIA+ communities and reducing discrimination. This was all done on the basis of a petition that was filed by a lesbian couple. [Ragamalika is referring to the petition filed by S Sushma and Seema Agarwal that led to Justice Anand Venkatesh rebuking the practice of conversion therapy.] Justice Anand Venkatesh then assembled a set of guidelines and called for the attention of the Tamil Nadu government. At this point, while all of this was happening, QCC and TNM decided that, on the back of that conversation that we had during the QCC Lit Fest, we needed to do something more with media houses and journalists. Because QCC has been conducting this litfest since 2018, we had already heard from a lot of media persons who pointed out and felt that the problem really lay in not knowing what the right language to use was and that while the English media might have a better availability of resources, this was not the case with other Indian languages.

We came together on the strength of the work that we had already done. QCC has already been at the forefront when it comes to talking about language around queerness in Tamil. And TNM has been at the forefront of reporting sensitively about LGBTQIA+ issues. I think it was in 2016, that we did a series called Let’s Talk LGBTQIA+, and in that series we compiled a list of terms for LGBTQIA+ identities and what they meant. We wanted to pool our resources. TNM also already had a small style guide, one that we used internally, with guidelines on how to cover LGBTQIA+ issues sensitively. Like with any project, as we kept working on it, we found more partners along the way, and that’s how Inqlusive Newsrooms is now supported by Google News Initiative. Now that we had that, we could expand on our dreams and our vision for this project. We can now publish the guide as physical books and send it out to people, provide fellowships, and really let it take shape.

What were the challenges you faced while launching it, and what are the challenges now, now that it’s out there?

If we had to talk about challenges, we are, of course, a small team working to put this together, but we’re very excited. No one came up to us and asked us to do this. We came to this because we wanted to. We’re going to be involved in every aspect of this process. TNM has a history of doing sensitive stories, including on LGBTQIA+ issues, and we are proud to be a feminist newsroom. We have been sensitive in covering caste, class, and marginalisation of all kinds. We are leading this along with our partners QCC and queerbeat. queerbeat is going to be a part of the localisation of the guides into Hindi and Marathi, and they’re going to be a part of the trainings in Hindi, as well as the fellowship. The people who are doing this are queer journalists, writers, designers and activists. And who else and who better to do this?

We are not outsiders or consultants taking on a project. We are not inventing new words. We are not looking at it from a very linguistic point of view and saying, “These are the words, and this is how it translates into another language.” That is not our aim at all. We are curating terms that are used by various LGBTQIA+ communities in their languages. Some of them might be reclaimed slurs. But what are the terms that are owned by the communities? What are the words that communities are comfortable using for themselves? That’s what this is about.

What does an inclusive newsroom look like to you?

An inclusive newsroom is one where there are a lot of fights. It’s one where people are passionately fighting about the things that they believe in, where you’re not going to look at a set of people who are all homogenous. It’s one where the physical newsroom is filled with enough representation, not just in terms of ticking boxes but in terms of actual stakeholder involvement. Who are the people whose voices are being represented? Anything that is homogenous, is not an inclusive newsroom. An inclusive newsroom is also one that doesn’t say they are not going to look at something as an issue because they don’t understand it. Once you have enough stakeholders in a newsroom, there is enough diversity to ensure that that never happens.

Zoë Liz Philip is a Communicative English major and an occasional observer of city culture. You can listen to her on the podcast The Bangalorean Dater.

Media Reference Guide in English (click here to download):

Inqlusive-Newsrooms-LGBTQIA-Media-Reference-Guide-English-2023-e1