Speakers at the public meeting of the NWMI’s 17th national meet fell on both ends of the spectrum—benign benefactors who believe newsrooms have achieved inclusivity and those who called out the shortcomings of the media when it comes to equal representation. It provided a glimpse into the voices and challenges in today’s newsrooms.

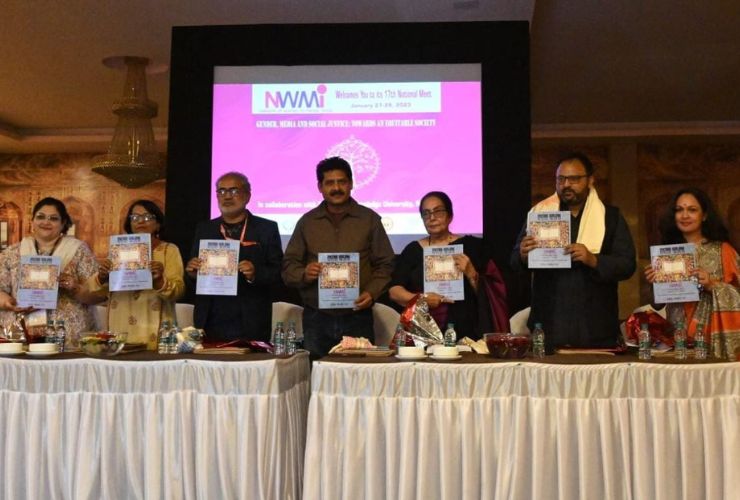

“It takes a lot of courage to stand up and speak, but it is also courageous to sit and listen,” said Sumita Jaiswal, co-ordinator of the Bihar Chapter of the Network of Women in Media, India, while opening the public meeting of the NWMI’s 17th national meet. It was a heart-warming message for the 150 journalists from across the country who were present for the meeting on January 27, 2023 at Hotel Pataliputra Nirvana in Patna, Bihar.

Discussions, arguments and debates about the role of media, gender justice and fundamental rights for all filled the three days. The theme of the meet was Freedom of Expression: Media, Gender and Social Justice, a particularly pertinent one given the developments of the past few years, both within the media and in society.

Freedom of expression is not just a media issue but a matter of public interest and importance as the foundations of an equitable society depend on widespread (if not universal) access to fundamental rights, including freedom of expression, which includes media freedom. The public meeting tackled these issues, and served as a strong starting point for the conversations of the next three days.

In her inaugural address, Justice (Retd) Mridula Mishra, Vice-Chancellor of Chanakya National Law University in Patna, got straight to the theme of the meet. Referring to the Preamble to the Constitution and its dictum of justice for all, whether political, economic or social, she pointed out that the media’s role as the fourth pillar of democracy is critical to create awareness. “Are the women journalists given the same role as male journalists? Are they safe? Are they secure?” she asked. “Can they claim equality or can they rise to the same level as the male journalists?”

She said that a recent report had indicated a drop in the number of women journalists, especially in print media. The role of women in television has not been affected, largely because the shows “have to be seen as attractive”, she said. She added that everyone, whether an individual or a private organisation, should speak against any government decision, policy, act, rules or regulations that impede the progress of women. Justice Mishra released the souvenir of the public meeting, ‘Patna Kalam’, a collection of articles on issues of gender and media.

The NMWI story

A collective that enables women professionals in the Indian media to share information, exchange ideas as well as support one another and advocate for gender justice, NWMI has been in existence for 20 years. Senior journalist Shahina K.K., who is one of the founding members of NWMI, and Yirmiyan Arthur, a relatively new member from Nagaland, introduced the collective that came into existence on January 30, 2002.

Shahina explained that the NWMI emerged from a ground-up process involving workshops in several regions before consolidating at the national level, The network has remained “non-hierarchical and informal, without an office, office-bearers or funds.”

Taking forward the story, Yirmiyan, who has been a member for three years, explained the ownership journalists felt for NWMI, and the knowledge, support and solidarity the women provided for one another.

NWMI’s national meetings were hosted by regional chapters, while funds were raised by collaborating with local, like-minded groups, universities, industry and even government departments. “However, NWMI never lets anyone fix or determine the agenda. The members alone decide what the subject and who the speakers should be,” she said.

NWMI stands for women journalists, their rights and professional ethics, she explained. It provides support and fellowships to journalists, especially from marginalised sections and localities, and is a platform for journalists to come together and share stories, ideas and contacts in this competitive world, she explained. Members are regularly updated about job openings, initiatives, scholarships, research seminars and workshop opportunities, levelling the playing field for journalists from across the country.

“Finally, NWMI does not believe in being mechanically ‘objective’ but in taking positions whenever human rights are violated or wherever injustice happens,” she said, citing its stance on harassment of women journalists in the workplace, or by the state or police. After 20 years of togetherness, the members proved that it was important to nurture harmony, unity, trust, love, camaraderie and solidarity. The strength of the collective lay in every woman, with their diverse, varied talents.

BIHAR IN FOCUS

Eminent journalists from Bihar provided quick takes on the history of journalism in Bihar over 20 years, in the context of the state’s development and growth, as well as provided a glimpse of the attitudes towards gender and inclusivity in newsrooms.

Ashish Mishra, Special Correspondent at Hindustan, Patna, began by describing the predicament of a journalist in an unequal society: “Jawaab rakhe rakhe sawaal ho gaye, Ab toh khud se mile bhi kayi saal ho gaye’ (Answers have been delayed so long that they have become questions. Now I feel it’s been years since I met myself.). He said journalism valued professionalism above all other considerations, including gender. ‘Jiski jitni bhaagedaari, uski utni hissedaari (An individual’s entitlement determines his or her share), he explained, adding that one’s journalism, therefore, tended to reflect the privileges, education and awareness of one’s upbringing. Having started his journey in theatre, he conceded that the challenges in the media were different from other industries. Making a pitch for his newspaper, he said that in the past few months, about 60 per cent of the journalists recruited in Hindustan were women. “Things are changing and there are 11 women in the Editorial,” he observed without mentioning the total staff strength in the newsroom. “Still, as a media house has very few hands, more men are taken. I would request everyone to come out of their comfort zones,” he added.

Brij Mohan, Editor of News 18, said that people across the country were curious about Bihar and the changes it had undergone socially, politically and economically over the past 20 years. Recalling that he had worked in Delhi, Chandigarh, Ahmedabad and Hyderabad and had travelled across India, he said it was mindsets that defined people and regions. “In the whole of India, barring the South, Gujarat and to some extent the north-east, society is still patriarchal. People still don’t agree that women in the media, especially in print, should go out and report.”

He recalled that while overseeing Bihar and Jharkhand for a couple of years and facing some pressure to recruit women, he took in fresh graduates from universities or those who had experience of two to four years. After keeping the seats vacant for a year, he finally did succeed in filling them with women. He also commented that it was not correct to say that women could not take up political reporting. “It was a girl with just a year-and-a-half of experience in my team who was sent to cover the CM’s beat in Gaya at a time when Gaya faced water scarcity. The girl was handpicked from among 100 or 200 reporters by the CM to interview him” he said. “She disproved the belief that girls could not report on political issues, a mindset that we should all come out of, so that we can give a representation to the section that makes up 50 per cent of the population,” concluded Brij Mohan.

Noor Alam, Executive Editor, Taasir, said Urdu journalists faced more challenges than others. “Even after putting in a lot of effort, we are not able to fulfil the basic responsibilities of journalism.” In spite of social media and advanced technological support, the women in Urdu journalism have not benefitted. This was not due to the lack of abilities or support, he said. A number of women from Urdu-speaking families were joining the administrative services, teaching, or Panchayati Raj institutions, where they became leaders, but the situation in journalism was discouraging, he said. This was a huge challenge for the Muslim community and he requested women journalists to take on the responsibility to address it.

How many of us can speak? How many of us from the media in the world’s largest democracy of the world know the stories that we are not even able to tell? said senior journalist Geeta Seshu.

DEBATING CHANGE

Introducing the panel on Freedom of Expression: Media, Gender and Social Justice independent journalist Geeta Seshu recalled recent incidents of harassment, intimidation and imprisonment of journalists in an effort to curtail free speech. She mentioned the central government’s ban on a BBC documentary; the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology taking down any report deemed to be fake by the Press Information Bureau; the directive given to journalists to disclose sources; the gag on journalists reporting from Joshimath and several journalists in custody. “Asif Sultan of Kashmir has been in jail since August 2018. Siddique Kappan is still in jail for a story that he didn’t even get to write. Journalists are prevented from flying out of the country and charged with criminal sections of the Indian Penal Code and the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). Many are attacked online and physically too. Journalists are killed and that, as is well-known, is the ultimate censorship,” she said.

The impunity for these crimes is staggering, as there have only been three convictions in the last 22 years. “The political sanctions for the killers of those who were convicted of the real murder of journalism was incredible,” she said, giving the example of the chief of the Dera Sacha Sauda being greeted by BJP members when he got parole despite his conviction in the murder of a journalist and the rape of two women. “How many of us can speak? How many of us from the media in the world’s largest democracy of the world know the stories that we are not even able to tell?” she said.

Seshu moved on to the effect of the pandemic on journalism. Many NWMI colleagues had lost their lives while reporting on the pandemic, while others had lost their livelihood.

Contractualisation had struck a body blow to journalism and to the independence and collective strength of journalists, while neoliberalism had made advertising and public relations much more powerful. “The government is the biggest advertiser in the five-year period between 2017 and 2022, having spent Rs 3,339 crore on advertising, based on information given by the Information and Broadcasting Ministry in the Lok Sabha. Despite the reach of the Hindi media, the Times of India received the highest amount for advertising, between 2017 and 2022,” she said.

Media ownership too had shifted. “Big business has mopped up large slices of the media, which is an issue of concern. The commitment to journalism is about real issues involving marginalisation, inequality and justice,” she said, while adding, “How can one hold on to these issues and push back? How do we regain lost ground?”

Dhanya Rajendran, Editor of The News Minute and co-founder chairperson of Digipub, spoke on the legal challenges faced by digital journalists, especially with intermediary guidelines and the code of conduct. She started with the observation that “NWMI is not an organisation but a system. It’s a sisterhood in which people come together when one person is in trouble. This room is full of very powerful women journalists, who can actually help to topple the Modi government.”

She said Shahina K.K. and Neha Dixit had faced many cases for their reporting as has Rohini Mohan, who had reported extensively on the Citizenship Amendment Act from Assam. “These are all dangerous issues, for which they have become targets of governments,” she said.

The legal challenges they faced for questioning injustice were similar: the use of UAPA and sections relating to sedition . “In Telangana recently, we reported about a journalist from the BJP spectrum, who was jailed while multiple cases were filed against him. The moment he got away in one case, he would go to jail in the next one. We have seen that in the case of Mohammed Zubair.

“Regarding the digital media rules, I am one of the first litigants with The Wire, who went to the Delhi High Court against the digital media rules. I’m in a small website, but there are smaller websites with just 10 members that face FIRs against them,” she said. “That is a huge burden for a small organisation.”

Another rule insisted on the formation of a committee, with a former judge and two or three eminent persons to oversee a digital publication’s work. Every organisation would not be able to form these panels and would definitely be part of other organisations, such as Digipub. “The government therefore has made the rules very difficult and problematic,” she said.

In a discussion with authorities about YouTubers, Dhanya shared that they asked whether people on YouTube, who were not journalists, but who discussed news, were also supposed to be under the digital media? The authorities were not sure. She also talked about the conflicting rules applied to the Press Information Bureau (PIB) Fact Check Unit rule, which will be applied only to the digital media. The amendment said that any business with regard to the central government can be fact-checked by the PIB. Dhanya added, “This is a way of censoring media, so the voices opposing it should be strong.”

Dhanya said mainstream or legacy media houses, including every newspaper regarded as progressive, and television channels, had not supported digital media. In 2021. On the contrary, they met the central government to specify that the new rules should apply only to the digital media as news channels were already supervised by the National Broadcasters’ Association and newspapers by the Press Council of India. “They literally threw us under the bus. The lack of unity in the Indian media, especially the legacy media’s reluctance to take on the government, is very problematic.”

Later, legacy media houses wrote editorials against the rules, but only the small digital media houses that went to court to challenge the rules. “It is important that everyone speaks in one voice against these amendments,” she said.

To a question on what the media can do to combat hate speech, Dhanya said people could look at the example of ‘Hate speech beda’, a collective of journalists, lawyers and students in Bangalore that tracked hate speech on television. The group has filed many petitions with the National Broadcasting Association, which has “censured and even fined one of the (channels)”. “The media in every state has to start doing it, because once you file a complaint, the NBA cannot sit on it, but has to act,” she explained.

The challenges to free and fair reporting have always been many, said Manikant Thakur, senior journalist, formerly with BBC (Hindi) in Patna. He said that the venue they were in had once been the offices of the Indian Nation and its Hindi edition, Aryavart. “They did extremely well, but after they folded up, the hall has now become the venue of the meeting.” This, he said, underlines the state of the media in Bihar today.

It was in Patna, 40 years ago, that the heavy-handed Bihar Press Bill was mooted by then chief minister Jagannath Mishra. “The Press Bill was intended to muzzle the journalists, adding IPC 193-A, making it dangerous to talk against the government. Anyone who did would be slapped with the non-bailable warrant and would be arrested even without being told of their crime,” he said. “The media took up a march from Patna and all other states to Delhi against the Press Bill. It created a storm as they all marched right upto Parliament, and though it was felt that after this march, no government would be able to do what it wanted. Public pressure forced the government to take the Bill back.”

Even after a change of regime, there was little support for freedom of expression and the media. The Nitish Kumar government, which followed Lalu Yadav’s, did something similar. . “In 2021, they released a circular, with a similar framework, from the Additional Director of Police, specifying that if anything controversial was written against the government or ministers, it would be considered a crime and according to Cyber Law, there would be action taken against them. It was issued by the government in a situation of deteriorating law and order.” By issuing this circular, the government felt that it could avoid criticism, he said.

“However, the Bihar Working Journalists’ Union was so strong and opposed the Press Bill so firmly that the government did not have the courage to implement it,” he said. It used to support everyone in the Press, whether they were journalists or working in the printing section. “However, over the years, this solidarity and support has come down for the journalists.”

He said the challenges to the media could be classified in two types: first, from the government and second, from within. Owners of media houses did not allow employees to write anything against the government, which might subject the management to punitive action and stop advertisements. “The message given to the dailies was that if the government does not like what you write, it might stop the advertisements.”

He mentioned another challenge: “One section of the workers might want to surrender to the management, so even if you want to be pro-people, what can you do?”

Still, government cannot kill the media, even if it might pressurize it for a while, he said.

Meena Kotwal, editor, Mooknayak, said dalit, lower caste and marginalised women were underrepresented in the media. She cited reports from 2006 and 2019, which showed that the representation of dalit women in media was low, although there might have been some marginal improvement. The discussions about the specific struggles of dalit and tribal women were practically non-existent, she said, adding that this was the case even in the NWMI meet.

We are not spreading casteism. It already exists in society. We are just standing with a reflecting mirror. Do not break the mirror. Just change your face, said Meena, editor of Mooknayak.

“People don’t want to work under dalits and tribals in leadership positions, so casteism takes a different shape. It is not literal untouchability, especially in the urban context, but it is in the mind,” she said. “People are not allowed to rise up the ladder and their CVs get cunningly rejected even before they give interviews,” she said.

She said that women from the marginalized sections should be allowed to tell their own stories. These stories should not be narrated by the upper castes, “because those narrators will only tell stories in a way that won’t harm themselves, so they won’t even be complete stories.”

As the founder of Mooknayak, Meena said that they were often blamed for talking about caste by people who said that it did not exist anymore. “We are not spreading casteism. It already exists in society. We are just standing with a reflecting mirror,” she said. “Do not break the mirror. Just change your face,” she said.

Striking an entirely different note to Meena’s strong voice of justice and equality, Pushpendra Pal Singh, Media Educator and Head of Public Relations Society of India(PRSI), Bhopal, said women were finally outnumbering men in media institutions. “In 1991, when I joined a media institution, I found that there were hardly two female students. A few years later, I found that among 25 students, there would be about seven to eight women. By 2008 to 2010, our classes had 80 per cent women.,” he recalled. “Earlier, women were told to cover soft stories or features, but I would say with pride that we exposed them to better reporting.”

However, while discussing the change that had taken place and in a comparison between Bihar and other northern states, he recalled how they had discussed eight to ten years ago about the situation, “If a daily published anything in favour of a legislator, an intolerant public would burn its copies outside the office in protest. Such a reaction was not seen in other states. The public in Bihar is highly politically aware and demands to know how the paper could publish an article favouring the legislator. Many times, the daily would have to retract its statements,” he said.

“As I’m communicating with the public in the last eight to ten years, I’ve realized that the tussle between journalism and ‘jansampark’, or public relations, is like that between a snake and a mongoose. This is not a new tussle and has been happening from the 1950s, when the big industrialists opened PR sections in their companies, but it became stronger after globalization, after the bigger corporate houses understood the importance of public relations.”

There are two methods to attack media freedom he said: the first a violent attack on the media, and the second a ‘soft’ one of manipulating the media through public relations. “I think that the threat to the freedom of media has reduced due to the proliferation of various kinds of media. Earlier, there used to be the monopoly of a daily in a state, which used to decide the policy, the fate or literally the success or failure of a legislator. Today there are four or five bigger newspapers in states. TV channels came up only after 2000.”

To illustrate his point about the importance of an honest media using its circulation to hold governments to account, he spoke about a popular Hindi newspaper that had not received government advertisements for two years as its reporting raised uncomfortable questions. “But it continued to stick to its stand and refused to compromise, such that the government finally had to bow and restore the ads,” he said. Another newspaper’s editor who wrote scathing editorials suffered a similar hit to revenue, but the after a while, since the editor did not back down, the government had to restore advertisements.

“The media should not compromise, but should continue to take its stand and draw from its own inner strength. If you are honest, courageous and strong enough to take a stand and stick to your point of view, then you can hold up the importance of strong and ethical media, which is able to withstand any problems in its way,” he said.

Kiran Shaheen, senior journalist and media activist, raised the idea of democracy. “What is the measure of democracy,” she said. “Can one check whether it’s a participatory democracy or not? Do the people who run the government and country show transparency? Third, are the people who are governing the country competent enough to run the country?”

Kiran Shaheen said India on lagged on all three parameters.

“When I examined two dailies for a month, from mid-December to mid-January, I found only three reports on the girl child. There were only seven reports on dalits. I find that news related to dalits is not featured in newspapers unless they are beheaded or killed. These issues can get solutions only if we talk not just about social justice but about social injustice,” she observed.

“When we talk about social justice or representation of women in the media and many people are celebrating that they have got into media, I’d like to ask what difference does it make qualitatively, even if they do get represented?”

Although alternative media is trying to do some work nowadays to give a voice to women, it is missing in mainstream media. In any newspaper with 12 pages, you will get just 20 to 30 cm of space for women, that too without prominent placing. Regarding the schools that teach media literacy nowadays, it is clear that they do not instruct children about political perspectives or political correctness. They only impart skills about drawing together the content that can be presented in a certain manner, to convey a certain picture and image for the market. So you hear all those stories about women not having the skills to join or not being interested to fill in the spaces in the institutions.

She said schools also needed to inculcate political perspective and awareness in children. “I would say that our education system itself is faulty. It does not teach the students the central meaning of media… they are not able to see that those who are speaking in the media have 90 per cent privilege to speak. We need to take social and critical audit of the situation, so that we can give the correct picture,” she said.

Privilege to speak as well as freedom of speech and choice were addressed by Shahrukh Alam, Supreme Court advocate and columnist. “How is it that people like us, who champion free speech, at the same time are problematising it? How do we do that? To answer that, I want to start with the idea of false equivalence,” she said.

Two things that are seemingly realised as equal aren’t equal in reality. Lawyers and journalists are always told not to politicise things or bring in negativity. To help understand what it means to politicise something, it’s critical to answer two questions, she said: ‘Who gets what’ and ‘says who?’, referring to American political scientist Harold D. Lasswell’s work.

“And politics is also about changing that equation about whoever gets to make the politics about who gets what. Even here, in our panels, some speeches were deeply political, because the gentlemen were talking about ‘who gets what’ in a particular newspaper or channel, where they pinpoint the number of employees and jobs reserved for particular sections.”

If one followed this up with the question, ‘says who?’ the answer would be, “Says the gentleman. That is deeply political,” said Shahrukh. “It was followed by Meena Kotwal’s speech, which I think was also deeply political. But the difference, to my mind, was that the first political speech was the default politics, the politics of status quo, implying that whatever is happening, let it go on, but we alone will decide who will get what. Meena’s speech was disruptive, a speech creating a law and order problem. Her point is: ‘we are here too. We will decide who will be part of your organisation and will decide how many of us will join you, or perhaps will not join, or maybe set up our own platforms.”

To Shahrukh’s mind, that was a politics of inclusion, “that is demanding that I will participate on my terms, not on your invitation. So, it’s a bit like talking about material resources, food security, education and health. Do we as citizens, or even as refugees have rights to those or are we ‘labhaartis’ (beneficiaries), which one PM scheme or the other will give to us as largesse, after which it will be withdrawn and buried.”

The first politics says that ‘we have kept jobs for you. Do come.’ And Meena’s point was ‘Sure, we will come, but when we want.’

“Politics is about asking for change, inclusion and more participation. Politics is also about obstructive change, saying that you are being disruptive, you are causing a law and order problem, you are being anti-national, you are an artist … and what have you. So this is all about politics, but there is a world of difference in these politics.”

Likewise, she said that while talking about the neutrality of speech, we were told that all of the marketplace of ideas and of free speech, where every speech had an equal chance, made it clear that you could speak, but the channels, newspapers, police, institutions and UAPA all belong to the system. So it was not neutral.

“I want to submit that hate speech emanates from a deeply non-democratic space. Hate speech is about the politics of exclusion, politics of discrimination. Free speech, on the other hand, is democratic. Free speech is what Meena is talking about. It’s about the politics of more participation. Hate speech is not about causing offence—that is not its problem. Hate speech is systemic. It feeds into the system of discrimination and hates the problem. The major problem with hate speech is that it excludes, discriminates and pushes people and certain communities out of social, political and economic spaces.”

Hate speech is cumulative; it is fed to people in small doses, starting with one incident, and its impact is felt elsewhere over a period of time. Going back 30 years, she said: “When we were in school during the Babri Masjid demolition, no one came to us and said, “You are Muslims, so you do land jihad, so leave.” Over time, though the grievances against Muslims were built up, accumulated and presented in various ways—vote bank politics, appeasement of Muslims, questions about religious freedoms, Muslims as invaders. “Now it has become major issues such as land jihad, love jihad and what have you.”

Shahrukh continued, “Though this is provocative, I’m going to offer this to you. Hate speech is always an aid of power. It never challenges power. So that is the big difference between hate speech and dissenting speech. Hate speech has to be looked at as something that targets marginalised people. When you target the Prime Minister or someone in power it can be very offensive, but it’s not hateful, because there is no way that your speech, coming from the position of marginality, can push them out of the positions of power, or extrude them. They are so entrenched that it doesn’t push them out.”

She gave the example of Akbaruddin Owaisi’s speeches, which she found to be deeply offensive, violent and criminal. Yet it was not hate speech. “It does nothing except offend. But when people in power, such as a minister says something that is hateful, it has the power to actually exclude me. I learnt that.”

She said that if you looked at the Prevention of Atrocities Act, or at IPC provisions that utilise certain kinds of speech or abuse directed at women, it recognised that hate speech was something that was targeted at the weak, not the other way round. “These particular acts and laws recognise this, but I also believe that it should not be legislated for Muslims, who are not homogenous but stratified. So the way hate speech affects a Pasmanda or working class Muslim is very different from the way it affects the wealthier Muslims. So it should not be legislated as one, but it’s something to think about.” She added that the problem was that because it was cumulative, you cannot really criminalise all of it. “You do have to think about recognising it as a constitutional wrong, maybe bring civil changes or something for a constitutional law.”

There is nothing democratic about hate speech. Hate speech is about the politics of exclusion, politics of discrimination. Free speech, on the other hand, is democratic, said Supreme Court advocate Shahrukh Alam.

TIME FOR QUESTIONS

In the question-and-answer session, independent journalist Revati Laul said politics could not be ignored even while providing justice. “It is not right to categorise people as perpetrator and victim, because it sets up a fresh cycle of violence and ignores the politics underpinning it. That needs to be looked at. Even when gender, caste and religion are looked at, and we look at who has power and who doesn’t and sectionalise people, we are not finding a solution,” she said.

In response, Shahrukh said: “In the vehicle of the regime, language is insidious, something that finds its way to invert feelings and is the logic of the law also. It’s becoming impossible now to criminalise things, which form the language and logic of the law.” She read out portions of an affidavit by a petitioner in the Anti-Conversion case. It said: “Hinduism and Hindutva is the ancient culture and the lifeline of India. Hinduism is a Dharma and not merely a religion. In their zeal of conversion, Muslims and Christians have killed billions of people, raped millions of women and destroyed millions of temples and other worship centres. They have completely destroyed many ancient cultures like Mesopotamia, Rome, Egypt etc.”

On this, she observed that whether the case is won or lost the affidavit is now part of the archives of the court. So this language, logic and history has entered the court. The point is that it should not and cannot be criminalized, but is now part of the same archives. “I think the only way is to prevent hate language as it has been done. Language is the answer. It has to be done at the level of schools and colleges and just talking to each other.”

In response to a question on how the media can fight hate speech and how the law can support people, Shahrukh said that Sections 153A, 295 and 505 of the Indian Penal Code all assume that offensive speech is the problem and that it is between equal parties. But that is not how hate speech operates. “IPC 153 or 295 assume that because they are equals, if you are offended, you will disturb law and order. That again is a wrong assumption, because with hate speech, it is always one way. It’s unilateral. These are not equal parties. So the framework of law suits equal partners, but that’s not the case here. According to me, the way a law is framed now makes it unfit and ineffective. In the worst case scenario of hate speech, only an FIR is filed and nothing comes of it, because it is looked at a one-off, not a systemic, structural problem. Nothing comes it, and it doesn’t disturb the system.”

Senior journalist Jyoti Punwani asked Shahrukh whether Akbaruddin Owaisi’s speeches could be called hate speech, as he ridicules Hindu gods and incites people. In response, Shahrukh said that Owaisi’s speeches were certainly offensive, inciting and criminal, covered by IPC provisions. “But I qualify hate speech as something that creates a democratic deficit by pushing one community or one people outside democratic spaces. I am saying that Muslims in India cannot do that. If he were to make this speech in Pakistan, then of course it will. But here it is just wild and criminal, not hate speech. Us vs Them, which does create communalism and division, is not progressive. But I don’t know whether it’s hateful. I don’t know whether Dalit or Muslim counterview is hateful in that sense.”

Kalpana Sharma, senior journalist, one of the founders of NWMI and an columnist at Newslaundry, in her video address, spoke about media, gender and social justice. “There is no complete freedom of expression in India, and the government can move in to restrict it. This is the debate, but I think in the last few years, the issue has a delayed urgency, because of both the overt and covert pressure on the media and journalists have had to experience, when they either do not toe the dominant narrative put out by the government, or when they decide that it is their job to question the policy and what is going on in the country.”

The government’s moves to interfere in freedom of expression is something everyone should worry about, she said, referring to a proposal to amend the IT rules to empower the Press Information Bureau—which was created with the principal purpose of putting out information about the government—to remove news it deemed critical of the government.

“This is happening right now in a country that claims to be the mother of democracy. We are not living in a state of Emergency, where our fundamental rights have been suspended. So why and how is this happening? I did feel a sense of déjà vu when I read this about the government, because perhaps a lot of people don’t know, but in 1975, when Indira Gandhi declared Emergency and suspended fundamental rights, the power to censor the Press was placed in the hands of the same PIB. At the time it was only Print, because there were no TV channels or digital platforms. At that time there was no fake news, but the government had decided on certain guidelines and news that violated them could be taken down. If the decision was made but you had to delete an item or article you could not argue with a sentence and the censor is not bound to give any explanation of why this was done during the Emergency,” she said.

At the time, Kalpana worked at the independent weekly news magazine, Himmat, founded by Rajmohan Gandhi. “What almost seems innocuous, that is those 26 guidelines we were sent and had to follow… how it actually works on the ground when you give power to people. Now it is often argued that media or freedom of expression are elite concerns… But during the Emergency, in fact, it was the elite that was least bothered about the absence of press freedom. They were quite content that there was some order in society and the country had a strong leader. It was evident that the absence of a free press meant atrocities such as compulsory sterilization or demolition of slums in Mumbai and Delhi were never reported. These stories actually came tumbling out after the Emergency was lifted. For the journalists of those times, we did know these were happening even though there was no Internet. We also could not report about human rights violations, about arbitrary arrests or any resistance,” she said.

She said that the corporatisation of media had further marginalised certain regions, groups and communities, and limited news reporting to “anything that sells the product”. Injustices against the poor, the marginalized or people living in Kashmir or the Northeast are reported only when the disaster is of a proportion that cannot be ignored. “News about the poor doesn’t sell the product… The narrative is determined at the pleasure of the powerful in politics and business. And journalists are reduced to manufacturers of news that would fit within the pre-determined mould.”

The absence of media freedom is inimical not only to the concept of democracy but also to social justice. She pointed to the growth of independent platforms as a sign of hope, alongside the fact that journalists continues to report on issues that really matter. “I feel at this point it is very important that we don’t throw up our hands and say that all is lost. I believe that in the toughest of situations, there are cases that could be used to get across the truth. If we don’t use and expand those spaces today, they will be closed in the future.”

In his closing remarks in a video address, Daniel Bastard, head of the Reporters Sans Frontiers (RSF) Asia-Pacific Network, said that in 2022, India was ranked 150 out of 180 countries in the RSF’s World Press Freedom Index. “With the end of NDTV’s editorial independence, recent attempts to ban BBC’s documentary about PM Modi and other government plans, the situation in India is extremely worrying. I can see some similarities with China,” he said.

He described government efforts to control the flow of information from certain regions and about certain issues by refusing journalists entry into some states as “extremely shocking”. He said it was important to keep freedom and democracy in India alive.

Report by Revathi Siva Kumar

Edited by Shalini Umachandran