By Supriya Unni Nair

Video editor Jisha Elizabeth

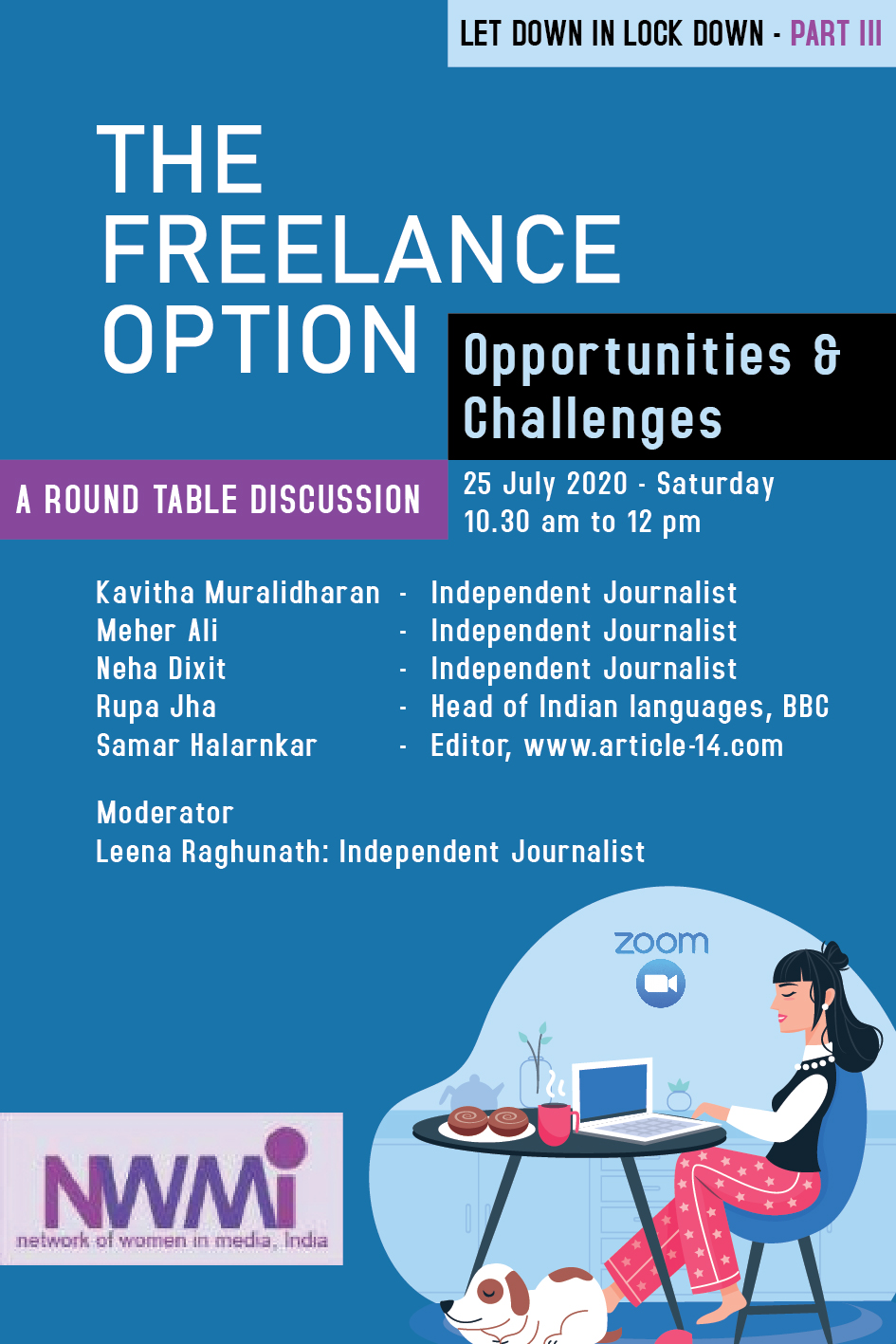

Panelists:

Kavitha Muralidharan, independent journalist; Neha Dixit, independent journalist; Meher Ali, independent journalist; Rupa Jha, head of Indian languages, BBC World Service; Samar Halarnkar, Editor, Article 14; Ashish Dikshit, Editor, BBC News Marathi; Leena Reghunath, independent journalist (moderator).

The importance of fellowships

Neha Dixit, who has been freelancing for eight years, emphasised the need for a journalist who decides to freelance to be patient. Citing her own example, she said that when she left television in order to work in the print media, she found that jobs were few and far between and freelancing seemed to be the best option available.

Initially, she approached editors she knew in the bigger metro cities. She said that the NWMI’s exhaustive crowdsourced list of editors, pay brackets and payment timelines was of great help to her during the initial days.

She underlined the fact that freelancing requires patience and trust in oneself. According to her, it takes at least two to three months to learn how to pitch stories and generate a monthly income – so it is worth trying to keep a buffer of at least three months for a freelancing career to take off.

Underlining the importance of pitching stories in advance, Neha recommended the practice of keeping two lists of ideas at hand, divided into short term and long term projects. If an editor declines a pitch for one of the latter, one from the former can be pitched immediately in the hope that it will be accepted.

Freelancers should also keep an eye on available fellowships and keep applying for them, she said. Warning that freelancing in India does not pay well, she pointed out that there is usually no option to ask for expenses for travel or any other news gathering activities to be provided. In such a scenario, fellowships represent essential support while working on stories that require such investment. She underlined that it is crucial to continuously apply for fellowships so that there is a chance of at least one out of ten applications succeeding. Neha recommended www.ijnet.org as a good source of information on fellowships and awards from across the world. She explained that most of these awards and fellowships offer money and this will help freelancers supplement their income and subsidise their reporting.

Neha also pointed out that the Indian freelancing scenario was tough because publications did not generally provide contracts for writers. She stressed the importance of and need to push for a contract.

She explained that freelancing is a full-time job which requires eight to ten hours of work a day. A freelancer needs to figure out how much money he or she wants to make in a month and then calculate how many articles need to be published in order to achieve this. She recommended pitching at least four to five articles a month.

What to ask of commissioning editors

Citing her own experience, Neha pointed out that payments can be delayed for a long time – in one case, the money due to her was delayed for almost 16 months. Recalling another incident, she talked about how she had received no help from the media organisation she had written for when she had to face legal issues over the article. They also denied her payments in her times of trouble.

She stressed the need to put in writing, at least in an email, details such as the specific time frame within which the organisation would pay for the piece, what responsibility they would take in case of legal problems (including expenses), and what support they would offer in case the writer faces any emergency. She also strongly advised freelancers to buy health insurance. Commissioning editors must also be requested to issue a contributor card, which can serve as an ID card while on assignment, she said.

Neha suggested that freelancers should try to set aside 30 minutes a day to send reminders to editors about payments (especially while writing for publications that do not make it a habit to ensure prompt payments). She said that a good practice would be to wait for two days after publication and then start sending reminders about payment. She emphasised that there was no need for writers to feel embarrassed or ashamed to ask for what is due to them. It is those who don’t pay who should be ashamed, she pointed out.

Branding through social media

According to Neha, social media represent an important tool for disseminating stories. Nowadays some international fellowships even ask for details about the number of social media followers a writer has. And millennial readers are now on Instagram. So, it makes sense to post one’s work on various social media platforms. Keeping a mailing list of people who are interested in the subject area of your work will also help in disseminating articles, she said.

Pros and cons of freelancing

Meher Ali, who is based in Aligarh, has been freelancing for seven out of her 11-year journalism career. She said she found that freelancing was not as easy as she thought it would be. According to her, freelancing has its own sets of pros and cons.

Elaborating on these, she said the advantages of freelancing are mainly that freelancers can choose their areas of interest, work around their own deadlines and pursue long-term projects of interest to them. There is scope to be identified with certain issues through one’s work. Stories may even have the potential to impact society and the world around us.

According to her, the challenges begin with late payment and sometimes no payment. Editors who are asked for payment sometimes get offended and see the query as ‘lack of trust’ on the part of the writer. Meher suggested that the timeline for payment should be asked about in detail in advance. If a commissioning editor is reluctant to provide this, they are not worth your time, she said. She felt that this criterion could be used as a filter that can help choose publications to write for: a good editor is usually upfront about payment models and timelines. Meher underlined that, apart from grammatical or factual errors, the last word on a story is always with the freelancer.

Take time off

She suggested that journalists who have been laid off should first take some time off – at least a week or two – and then take an inventory of stories done so far. A list of previous work could point the way to a niche based on the writer’s interests and inclinations.

She recommended that newcomers to the world of freelancing take advantage of courses and books on freelancing in order to gain a better understanding of the business side of freelancing and gather ideas about how to develop relationships with commissioning editors.

According to Meher, it is important for everyone considering the freelance option to ask themselves why they are doing so and what their motivation is. If there is no real answer to these questions, then they probably need to look at other options, she said.

She was of the opinion that potential freelancers shouldn’t jump onto the bandwagon before they have an income stream planned out. She also suggested that other journalism- related training and skills, such as editing and graphics, should also be seriously explored as alternatives to writing.

Meher outlined the challenges of reporting from a tier-two city in India. According to her, most freelancers from such locations normally and naturally feel a sense of responsibility to represent their cities, which are largely underplayed by the national media. The challenge is that editors generally want certain kind of stories from smaller cities, such as sectarian violence and, in Meher’s case, stories about Aligarh Muslim University.

She has found that stories on heritage, for example, were not in demand at all.

Meher pointed that the political scenario in India, especially in the wake of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA), has made it difficult for journalists to work without inhibition. Under the prevailing circumstances, it is essential for freelancers to chalk out how they can continue to work in a situation where their safety may be compromised, she said, and also be clear about the tools they need to cope with such stressful conditions of work.

Keeping an eye on awards

Meher suggested that those who get into freelancing should keep an eye on awards and apply for them whenever possible because they definitely help writers get recognition and be noticed.

In her view a freelancer should earmark six months to figure out whether things are working out – in terms of creativity, money and satisfaction. She also advised freelancers to be in touch with others in their community since freelancing can be a very isolating work experience.

Moderator and independent journalist Leena Reghunath also stressed the importance of having a community of freelancers who can provide mutual support. She pointed out that India is literally brimming with stories waiting to be told, but most freelancers are not sure how to go about it. Unfortunately, she said, journalism schools do not teach the nuances of freelancing. According to Leena, it is imperative for freelancers to pitch and brand themselves so that their chances of getting assignments go up.

Meher added that if payments were not up to the expected mark, writers should look at the option publishing their stories on their own blogs.

Dismal scenario in the regional press

Kavitha Muralidharan, who has been freelancing for five years after several years of employment with publications and writes in both English and Tamil (Tamizh), pointed out that more people seemed to be turning to freelancing in the wake of the pandemic-related layoffs. As a result, the freelance arena is throwing up even more challenges than before, she remarked.

According to her, in India it always helps to get pitches accepted if you know the editor, even though this not professional practice and needs to be done away with. Describing the dismal situation now prevailing in the Tamizh media, she cited the example of Vikatan Media Services, which had laid off at least 80 journalists in one go. All of those retrenched are looking at freelancing, she said, since the job market in mainstream media is abysmal and the payment models are atrocious.

Yet, she pointed out, opportunities for professional freelancing are almost non-existent in Tamizh media, citing the example of a journalist who was offered Rs 250 to write a column.

According to her, freelancing as a regional language journalist is very difficult. Even those who explore other avenues of work are finding it difficult, she said. A well-known Tamil journalist tried to start a YouTube channel, but this will obviously take time to monetise.

She herself helps regional language journalists to ideate and pitch stories.

Kavitha also suggested that freelancers should look beyond just writing. Translation is a good option for those reporting from smaller cities, she pointed out, saying that this would also help other local writers to come up.

Ashish Dikshit, Editor BBC Marathi, added that regional markets, mirrored in the Marathi market, are seeing a lot of people being forced to opt for freelancing. Payment is very low, and the budgets allotted for regional media are so small that it is difficult for commissioning editors to offer more.

He noted that the time had come to redefine the relationship with freelance journalists.

Pitching to editors

Samar Halarnkar, a founder editor of Article 14, explained that they work solely with freelancers. According to him, there is a mismatch between freelancers and independent media organisations in India. The biggest problem he faces as a commissioning editor is getting proper pitches, he said, pointing out that, in general, most freelancers do not pitch stories well and their ideas tend be unclear and vague.

He stressed the fact that freelancers need to convince editors that their idea will result in a worthwhile story. They need to detail the perspective and persuade the editor that it is worth his or her while to care about the story, he explained. Even follow up stories have their own importance, he pointed out, and freelancers should seize the opportunity to sell the idea as a larger story. The story developing around you has to be given national relevance, he said. So, the pitch should detail aspects that may be less widely known but are relevant to a larger audience. According to him, a good pitch should provide details of the background, cite potential sources and mention the timeline within which the story can be delivered.

Samar explained that a good story, delivered in the time promised, is the best way a writer can create a name as a reliable freelancer.

There is no substitute to keeping to commitments and deadlines and delivering good quality work, he said. If the pitch is good and the story is good, a commissioning editor is very likely to build a relationship with the writer, and once a relationship is built, it becomes easier to pitch. He was of the opinion that freelancers should look at building relationships with a few organisations instead spreading themselves out too thin.

Ashish Dikshit stressed the importance of contracts for freelance writers, explaining that the absence of contracts translates into an absence of responsibility and accountability on the part of commissioning editors.

As an editor he was of the opinion that, although all freelancers must insist on contracts, it is actually the responsibility of the commissioning editor to offer a contract and reassure freelancers.

Freelancers should be treated on par with employees on the organisation’s rolls, he said – for example, a freelancer should not be sent to report from a place seen as ‘too dangerous’ for a staff reporter. According to him, commissioning editors should also spend more time on pitches and give feedback on stories since this will serve to improve the quality of journalism. He also said that it was crucial for editors to make an effort to ensure gender balance while accepting story ideas.

According to Dikshit, freelancers must remember that if they are not provided with a monthly income from any media organisation, they are under no obligation to ensure exclusivity to a single media company. He said freelancers should not hesitate to send pitches to multiple commissioning editors. He also underlined the need for freelancers to look at acquiring or offering other skills, such as editing, videography and translation.

BBC’s model

According to Rupa Jha, freelancing and freelancers play a critical and relevant role in the BBC. They are rated very high in bringing in a critical edge to stories in the BBC’s Indian Language bouquet. As of now, they offer content in Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, Gujarati and Punjabi.

The BBC provides contracts, training and even equipment if required, she explained, underlining that their payment model covers travel expenses.

She clarified that the payment structure for the language services is different from that for the English service. The BBC has two kinds of freelancers: retainers who receive a regular, fixed amount, and others who are paid per piece. According to her, they try to pay on time. If an ‘idea’ is commissioned and they eventually do not use the story, they still pay for the submission, she said.

The main criterion for picking up stories is essentially ‘good ideas’, said Rupa, explaining that brilliant ideas and stories are the key to success.

Original ideas from the ground, which are pitched properly, are sure to work. She agreed that pitching is key to getting work, and that the pitch should clearly explain what was being offered, providing ‘a headline’ of the idea.

Since the BBC has its own staff in the bigger cities, they look towards smaller cities for stories by freelancers. Rupa clarified that they have facilities to translate stories, if required. According to her, freelancing opportunities are not just limited to writing. Story ideas for photo features can also be submitted. In addition, the BBC takes on people who have skills in production work – videographers, editors, and sound design editors, among others – on a freelance basis.

The problem of stolen stories

Neha Dixit suggested that commissioning editors should be asked to explain why a story idea submitted by a freelancer was given to someone else – on the staff or otherwise. She advised against calling out such behaviour on social media since that is bound to burn bridges, recommending emails cc-ed to other freelancers as a better way to build pressure.

Both Samar Halarnkar and Rupa Jha were of the opinion that editors who pass on ideas in this way were guilty of unethical behaviour, and that both the commissioning editor as well as the organisation involved were culpable. Rupa agreed with Neha that the freelancer should stand his or her ground and ask the concerned commissioning editor why they had passed on the original idea to someone else.

Ashish Dikshit pointed out that, ironically, the lockdown has led to a cut in the budgets available commissioning editors – so there is less chance of parachute journalists from bigger cities or even abroad being given someone else’s story idea now.

The round table was followed by a lively Q&A session, with the engaged 72 participants sending in a variety of questions.

To know more about other webinars in our “Letdown in Lockdown” series, visit https://nwmindia.org/initiatives/jobs-initiative/letdown-in-lockdown-jobs-initiative/