By Raihana Maqbool

Two years ago, on 5 August 2019, the Government of India, in an unprecedented political cataclysm- unheard of in the entire history of democracy- revoked the special status of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir and unleashed a reign of uncertainty, chaos and despair among the masses. The move was followed, almost instantly, by concerted efforts to muzzle Kashmiri voices and silence the media ensuring a complete chocking of voices of dissent. It was a difficult time for all, especially for people in the media and it remains equally challenging even now.

Having been working in Kashmir as a journalist for the last seven years, never have I witnessed such difficult times. Reporting in Kashmir has never been easy and there is always fear when we move out to report a particular story, but since 5 August 2019, fears as a journalist have only grown.

Information blackout

The muzzling of the media in Kashmir started with the information blackout after 5 August, due to which the press in Kashmir was virtually defunct and journalists found it difficult to find authentic information and report it.

The internet was suspended in the region and journalists had to depend on the media facilitation centre, the only place where there was access to the internet, with just a few desktops and no room for privacy. Nearly 200 to 400 journalists visited the centre on a daily basis and in between, there were people who were not journalists but managed to somehow gain access to use the internet. Everything in the centre was censored, as a few desktops were used daily by nearly 300 people on average. Millions of people were put under a complete lockdown.

The immediate days following 5 August, when the facilitation centre was not yet started, I remember journalists narrating how they took their stories in pen drives and handed them over to people, travelling outside Kashmir. The communication blockade even led me to travel to Delhi and removing all the two-factor authentication from my email addresses and other media. The internet ban in Kashmir continued for six long months.

Intimidation of journalists

Journalism and journalists in Kashmir were already suffering due to the internet ban, but it didn’t end there as journalists were intimated, attacked physically, threatened and were summoned by the security agencies. Now I feel that the fear has been institutionalized in such a way that it isn’t visible, but it is ever present. It is there when I report a story, or want to tweet something, but can’t.

Two journalists were booked under the draconian ‘Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA)’ in April 2020 and police summoned several others for their reporting and social media posts in Kashmir. These were journalists who were bringing out the real stories to the world.

For the last two years, journalists in Kashmir have been repeatedly summoned, intimidated and detained, and no action is taken against the accused police personnel.

Foreign journalists were denied permission to visit the valley, in an effort to clampdown on international attention.

India is already ranked 140th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, a global media watchdog.

The events that have taken place from the last two years have in a way led to journalists resorting to self-censorship. Many of my friends who are journalists say that they can’t write the stories the way they used to before the abrogation. Even before pitching a story, I think many times, whether I will be able to do this story, will I have access to officials and if yes, whether they will talk or not. As we saw during these two years, how officials denied information and quotes to the journalists.

New Media Policy: new media gag

On 2 June, 2020, the administration unveiled the ‘New Media Policy’ which according to them will examine the content of print, electronic and other forms of media for “fake news, plagiarism and unethical or anti-national content”. Journalists in Kashmir remained silent for a month and on 6 July, a group of journalists protested against the policy. The protesters demanded an immediate rollback of the policy and said they didn’t want to be a mouthpiece of the government.

Most of the journalists saw this 53-page document as a means to build only the government narrative and convert journalism into public relations. There were no consultations held with the local media before framing the policy. The policy is another way for the administration to muzzle the media in Kashmir.

Fears continue

Two years have passed and the events that took place in Kashmir after August 2019, makes me wonder, how safe is it for a journalist to report in Kashmir. I live in a place where even a small tweet on social media will put a person in trouble. I remember deleting a number of tweets from my timeline after many journalists we summoned for questioning. As a journalist, I always try to bring out the right stories from Kashmir, but even in those, there have been many stories that have left a mark only on my notebook.

We saw that during these two years, all the human rights activists have been muzzled in Kashmir and many stories have to be killed as no one is ready to talk on the record.

There is always a fear that keeps going on in the mind, that whether I should write this story or not. My phones notes and voice notes are full of narratives of people and their untold stories. The stories that I have not been able to write for many obvious reasons remain with me. Maybe, there will be a time, when I would want to tell those stories or maybe write a book.

—–

Raihana Maqbool is a multimedia journalist based in Kashmir has written about a wide range of issues, from education to sports to conflict.

Related

Reflective lens: The aftermath of August 5, 2019, in Kashmir

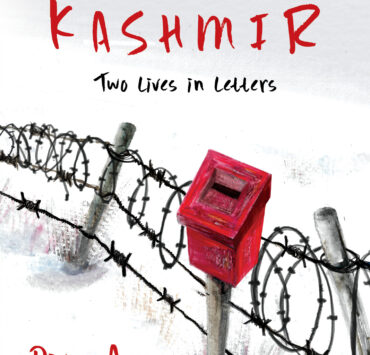

A Teen From Delhi, A Teen from Srinagar: A Remarkable Friendship Through Letters