By Ayswarya Murthy

A screening of Geeta Seshu’s documentary film chronicling veteran journalist Sabita Goswami’s four-decade long coverage of the violence in Assam and the North East, was organised by the Network of Women in Media, Bangalore (NWMB) in collaboration with the Press Club of Bangalore. The screening and discussion with the director, journalist Rohini Mohan, and academician Triveni Goswami Mathur on September 28, 2018, was attended by about one hundred journalism students and faculty along with NWMB members and other journalists.

Sabita Goswami’s autobiographical account, Along the Red River, starts with a quote about how pain nourishes courage and that people could not be brave if only wonderful things happened to them. The book is full of vivid and painful aspects of the veteran journalist’s eventful life but Geeta Seshu, Mumbai-based journalist and director of the documentary, says, the film focusses mostly on her eventful professional life, starting from working at Blitz to reporting for the BBC from Assam. However, at one point in the film, both these worlds come screaming and crashing into each other. It’s a moment that does justice to the film as a medium, as Seshu had so hoped. Sabita Goswami 2 It is November 1983, a few months after Assam’s bloody state elections, and chief minister Hiteswar Saikia is one of the most hated men in the state. At a routine official function, which Goswami figured she could safely skip, there is an attempt on his life by a young man. And the first thing he says when he is caught: “I am Sabita Goswami’s nephew”. After hearing the news from her colleague, Goswami dictates the story to her editor and excuses herself from further coverage of the event. And while she is away dealing with the fallout of this on her brother’s family, her daughter answers a phone call asking her to get rid of anything at home that might incriminate her mother in the attempt.

Sabita Goswami’s autobiographical account, Along the Red River, starts with a quote about how pain nourishes courage and that people could not be brave if only wonderful things happened to them. The book is full of vivid and painful aspects of the veteran journalist’s eventful life but Geeta Seshu, Mumbai-based journalist and director of the documentary, says, the film focusses mostly on her eventful professional life, starting from working at Blitz to reporting for the BBC from Assam. However, at one point in the film, both these worlds come screaming and crashing into each other. It’s a moment that does justice to the film as a medium, as Seshu had so hoped. Sabita Goswami 2 It is November 1983, a few months after Assam’s bloody state elections, and chief minister Hiteswar Saikia is one of the most hated men in the state. At a routine official function, which Goswami figured she could safely skip, there is an attempt on his life by a young man. And the first thing he says when he is caught: “I am Sabita Goswami’s nephew”. After hearing the news from her colleague, Goswami dictates the story to her editor and excuses herself from further coverage of the event. And while she is away dealing with the fallout of this on her brother’s family, her daughter answers a phone call asking her to get rid of anything at home that might incriminate her mother in the attempt.

A collective gasp went around the hall as Goswami narrates how her scared, teenaged daughter (Triveni Goswami Mathur, who has also translated her book from Assamese to English) decided to burn her entire collections of photos and documents. Every journalist in that hall, aspiring or otherwise, felt such a pang of loss for Goswami’s archives, rich from her coverage of the Assam agitation; the ethnic conflict and the violent state elections that followed; the various separatist and militant groups that were on the rise in the region; tribal conflicts and political upheavals. Rohini Geeta Triveni Through Goswami’s suspense-filled and almost cinematic anecdotes, Seshu captures an oral history of one of the most significant periods in Assam’s problematic and ongoing struggle with migration, a time when genuine concerns about land and people started taking on ugly religious and ethnic hues. Her initial sympathy for the agitation turned to horror and despair with each mass killing she reported on. As she counted the bodies of Muslims, often in remote settlements where Assamese mobs wiped out entire villages in a span of hours, she realised the leaders of the agitation were, at best, clueless or worse still, malicious; deliberately exploiting the psyche of the Assamese people for their own gains.

Sabita Goswami: A Journalist Remembers is a tightly-packed 40-minute film and the unassuming journalist’s simple yet powerful narration captures the spectacular events from her life in gripping drama and detail.

Sabita Goswami: A Journalist Remembers is a tightly-packed 40-minute film and the unassuming journalist’s simple yet powerful narration captures the spectacular events from her life in gripping drama and detail.

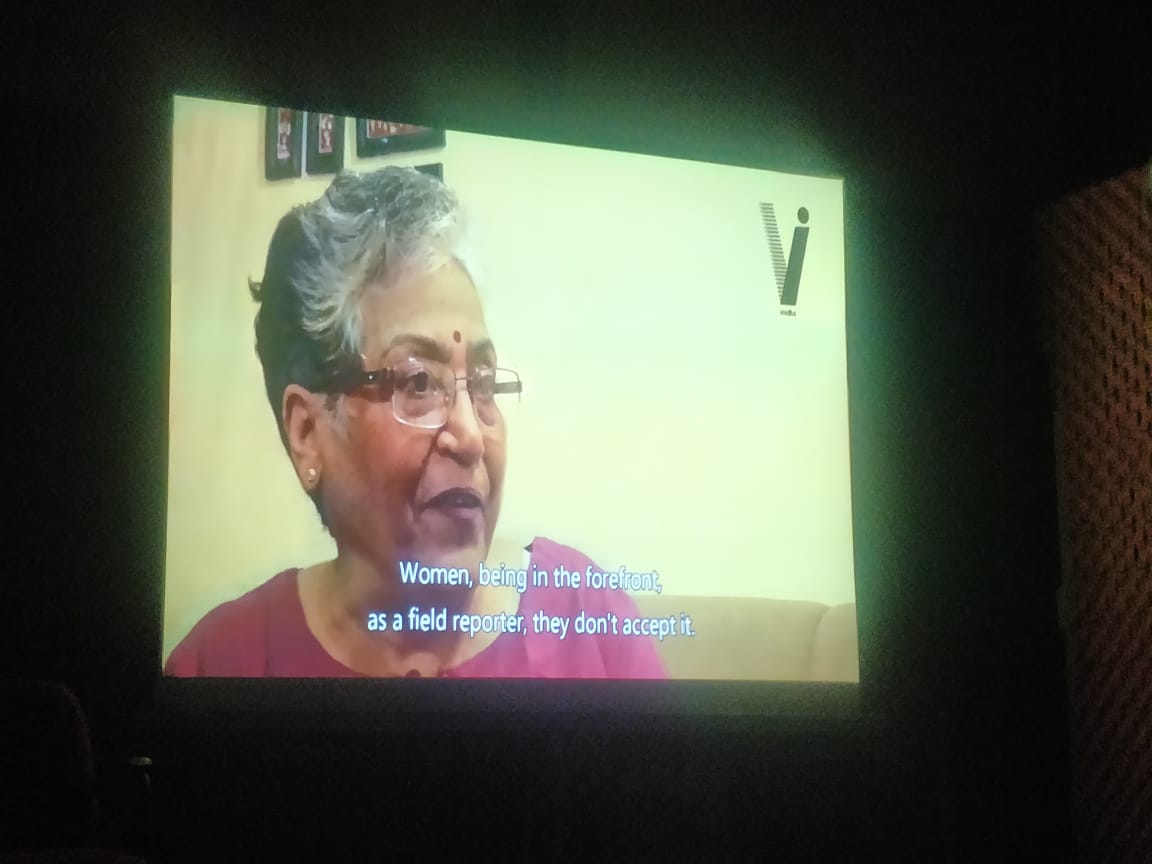

As a woman journalist reporting in the 1980s, her invisibility was one of her greatest assets, she says. During the peak of the agitation and violence, no one expected a woman to be on the field collecting information. They were ready to believe she was a social worker, and under cover of this anonymity, she broke several stories, most memorably the massacre at Chaulkhowa Chapori where more than 500 people were killed during the state elections in February 1983. An unlikely source, a small boy she had once helped, came to her that morning to tell her that a ‘war’ had broken out in his village. When all her contacts in the government denied anything at all was happening, she took a boat out to this remote island village, only to be met on the shores by injured and traumatised women and children; most of their men had been butchered by a mob not many hours ago. Despite these eyewitness accounts, government officials kept denying to Goswami that any such an incident had taken place. Finally, after getting the go ahead from its India bureau chief Mark Tully, BBC ran the story. It made a big splash at the 7th Non-Aligned Summit that was going on in Delhi at that time and embarrassed then prime minister Indira Gandhi. All the while, even Goswami’s friends and colleagues in Assam doubted something like this could have happened. However, when she headed to Chaulkhowa Chapori with a colleague a day later, other journalists were there too. The district collector, who finally seemed to have discovered the village on the map, says to her: “You brought me here”. And Goswami, even today, glows with the benign pride of a job well done.

Four days later, on February 18, the Nellie massacre was perpetrated and finally the world got to see the “Frankensteins” created by the Assam agitation. Goswami reckons that more than 7,000 people were killed in that area during that time; she personally counted 674 bodies that day.

Her increasingly vocal criticism of the agitation and its leaders had ostracised her even among the local media community. Assamese dailies were at that time pretty jingoistic about even horrific events like bomb blasts and violent attacks, and her non-partisan stance was not well-received. But fortunately, there were plenty of other people who appreciated her work – from senior bureaucrats to police constables and politicians to terrorists, “they all trusted me, I don’t know why,” she says genially. Even today women journalists continue to be cut off from certain sources of information, but Goswami knew early on and she was on her own and worked on developing rich contacts of her own across the region.

She recounts an incident, when she had gone to visit her nephew in jail where she was greeted by a prisoner, a young man she couldn’t place. He called her “Baideo” (elder sister) and told her who he was: ULFA’s Shailendra Datta Kolwar. “That is the kind of morality being built up by the agitation,” Goswami says towards the end of the film, and the panel discussion that followed only served to strengthen that argument.

When Seshu started out making the film, the updating of Assam’s National Registry of Citizens (NRC) had not yet entered the national discussion, though the NRC, a by-product of the Assam agitation, had been in the works for a while. With the Supreme Court order in 2014 asking NRC to be updated within three years, things started to move at breakneck speed and by July 2018 the state government had released, in two lists, the final draft of the 2.8 crore people whom it deemed had the legal right to reside in the state.

Bangalore-based independent journalist Rohini Mohan who has been covering the fallout of the NRC process says it’s hard to find moderate voices in Assam these days. She was present when the final draft of the NRC was announced during a press meet in Guwahati in July. The atmosphere of absolute pride and joviality that surrounded the briefing that would ultimately declare 40 lakh people stateless stunned her. Journalist and bureaucrats stood, hands to hearts, singing the Assamese anthem. “I couldn’t find a single Muslim or Bengali face there, joining in,” she says.

In fact, the atmosphere of distrust and insecurity that is the culmination of this decades-long undertaking has disquieted many of the locals. Mathur explains that the Assamese have a way of distinguishing the original Muslim settlers of the Assam, who came in to facilitate jute cultivation. “They are called Pamua Musalman and the more recent immigrants, irrespective of whether they are Bangladeshis or not, are called Miya”. Today the Musalman is just as scared and likely as the Miya to be pulled up and asked to prove his right to his land. “Even in the poorest of homes in Assam, they have all their documents in order,” Mohan says. “Because any day your neighbour will ask you to prove your identity.”

The question of ‘After NRC, what?’ had been always been looming in the background – what to do with the millions of people who had to be ‘detected, deleted (from voter’s list) and deported’? Mohan’s reportage to find answers to this question led her down a disturbing path.

The most immediate question is that of the 2.48 lakh people who have been declared ‘D Voters’ and foreigners. There are currently six detention centres in the state, which are actually just cordoned off sections of central jails, housing about 1,000 suspected illegal immigrants. No human rights activist save one has ever been allowed to enter these centres, where the conditions are reportedly dismal. Are more such inhumane detention centres going to be created to accommodate the newly disenfranchised? And then what, considering there is no deportation treaty with Bangladesh? She also touches on the problems with the NRC appeal process and the “sham of a foreigner tribunal”. A source helped sneak Mohan into one these tribunals during her recent visit to Assam and she had an opportunity to walk around and observe the proceedings. She saw a man’s plea being frivolously dismissed because he took too long to calculate how old his father had been when he was born. “There are about 100 of these judicial tribunals operating across the state and cases here are being dealt with by advocates not judges.” Everything here reeks of discrimination and incompetence.

As Mathur says, it’s impossible to predict what will happen next and what plan the government will come up with. “It is a staring contest,” she says. In the blink of an eye the cinders of Assam might fire up once again. For Goswami, who remembers an old Muslim man in Mangaldoi who had been speared through this chest, those years were nothing short of a “Greek war”.

Photographs: Top left: Sabita Goswami; top right (L to R): Rohini Mohan, Geeta Seshu and Triveni Goswami Mathur.

October 2018